Protected Bike Lanes Come to Comm Ave

Can they bring order to BU’s Wild West?

Every day on Comm Ave, cyclists dodge illegally parked trucks and swarms of students exiting Green Line trolleys. They swerve around construction barriers and skateboarders roaring at them head-on.

The existing bike lanes are an obstacle course of Uber and taxi drivers dropping off or picking up passengers, and delivery trucks with blinking hazard signals. Throw in heavy traffic, other cyclists who text while pedaling (no joke), and about 30,000 pedestrians a day, and rush hour can approach chaos.

Change is coming. Construction crews have begun building the city’s first protected bike lane, a mile-long stretch along Commonwealth Avenue from the BU Bridge to Packard’s Corner. And the emphasis is on protected. The new lanes will be for bikes only, and they will be defined by granite curbs between the sidewalks and street parking for cars, much like lanes already in use in Manhattan, Montreal, and Copenhagen. It’s part of a $20.4 million roadway improvement project funded by the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT), with help from the city of Boston and Boston University.

It’s a first in Boston, which has had a network of painted bike lanes for almost 10 years, but nothing like this.

“It’s a very big deal,” says Carl Larson, a BU Parking & Transportation Services manager. “Comm Ave has been hostile to people for a long time.”

The new lanes have been discussed and debated for more than a decade, but it was the 2012 cycling death of a BU graduate student that sparked change.

Crashes along Comm Ave number roughly twice the state average, city officials said last year.

The map above shows the location and number of bike accidents that the BU Police Department has responded to on the Charles River Campus between 2010 and 2017. Mouse over the map markers to see how many accidents have occurred in each location.

Despite the roadway’s hazards, the number of Boston cyclists continues to grow. Since 2007, bicycle use on Comm Ave has increased 47 percent during the morning commute and 135 percent during peak afternoon traffic, city of Boston officials say. Some good reasons for that upsurge: it’s efficient, fast, cheap, and it’s good exercise.

Robert K. Kaufmann, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of earth and environment, has been commuting from his Newton home to his Comm Ave office for nearly 30 years. His 30- to 40-minute ride is almost as fast as driving, Kaufmann says, and biking gives him an endorphin rush that he can’t get driving a car. He continues to ride despite a crash earlier this year that left him hospitalized for a week.

“Comm Ave is a disaster area,” he says, and he rides along Beacon Street to avoid it. “Cars need to understand there are bikes on the road and share it. That’s what these lanes will do.”

If the new bike lanes allow cyclists to feel safer, the number of riders could grow. Currently, only about one percent of people in Boston get around by bicycle, according to the city’s transportation planning initiative Go Boston 2030. City officials ultimately plan to quadruple the number of people who commute by bike while reducing auto traffic in the city, the report says.

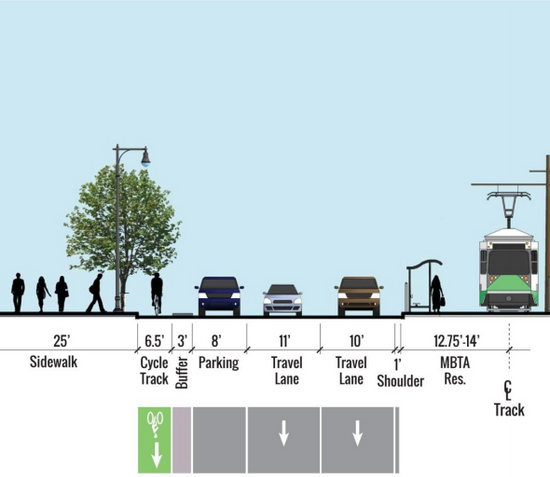

So what exactly is a protected lane? Contractors working for MassDOT have been sawing through six inches to a foot of asphalt roadway, removing tons of asphalt as they replace it with a track for cyclists between the sidewalk and a lane for parked cars. If the painted bike lanes along the roadway were the city’s first shot, these are version 2.0, built at a width of six and a half feet (less along some portions of Comm Ave, according to state highway officials), with a three-foot buffer between parked cars. They are sloped to prevent water from pooling, and city officials say they will be plowed in the winter.

One of the big benefits of the dedicated lane is protecting cyclists from getting “doored” by someone exiting a car.

Protected bike lanes also have better sight lines and greater predictability, not just for cyclists, but for cars, says Stacy Thompson, executive director of Cambridge nonprofit LivableStreets, which has long advocated Comm Ave improvements. The bike lanes, at least in theory, also remove bikes from roadways and sidewalks, returning roadways to cars and sidewalks to pedestrians.

“This demonstrates what’s possible,” Thompson says of the changes. “This is significantly safer for a person on a bike. We also hear from drivers that it’s less stressful. They know the road is more predictable.”

The bike lanes alone come in at about $2.5 million of the $20.4 million roadway improvement project that includes widening the Green Line trolley medians, repaving Comm Ave, and installing wider curbs at intersections for pedestrians. Sidewalks will shrink in some locations to accommodate expanded track space for people with disabilities and the new cycling lanes.

City of Boston officials have already installed a traffic light specifically for cyclists heading east at the BU Bridge intersection, a hot spot for crashes. About 2,000 bicyclists pass through the intersection each day, according to city data. (A second light for cyclists has been installed at the intersection of Comm Ave and Carlton St.)

The new system gives a green light to cyclists so that they get a head start and avoid a “right hook”—the collision occurring when a cyclist moves forward as a car makes a right-hand turn. Such lights are a preferred strategy in Copenhagen, where 40 percent of the population uses a bicycle for any trip two miles or less.

Whether bicyclists and cars will honor them in Boston remains to be seen. But bicyclists can get a $20 ticket for running one of the dedicated lights as well as for running a regular traffic light.

Watch this video to see how the new intersection at the BU Bridge uses new stoplights just for cyclists to reduce crashes. Video by Devin Hahn. Photo by Cydney Scott

Landry’s Bicycles spokesman Galen Mook (UNI’09), a founder of the bicycle-promoting student group BU Bikes, says such intersections are still not without danger. While he’s excited about the new tracks, he knows they won’t solve every problem. Pedestrians may wander into them, for example, and passing slower riders may be a challenge.

Mook says he will continue to ride with traffic in the roadway. But the new lanes will help would-be and less-experienced riders feel more comfortable using a bike instead of a car, he says, and that’s a huge benefit.

“If you have only a few blocks of protected lanes, then you ride back into anarchy, it’s not the fully desired effect,” he says. “But this is a good first step. Actually it’s a great first step.”

Megan Woolhouse can be reached at megwj@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.