Alternative Energy and Business

What to do now to help build—and prepare for—a clean, green energy future

In 2014, Boston’s political, civic, and business leaders pledged to cut the city’s greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent by 2050. Two years later, the city and surrounding communities went further, committing the metropolitan area to go carbon neutral by midcentury.

Now, the question is this: how do you get a city with a population of 600,000—which rises to more than one million during the workday—to alter the way it consumes and produces energy, how it manages resources and waste? And how do you persuade people to start working now to fulfill a goal that’s 33 years away?

“It is very ambitious, but in some sense, it is a well-defined problem,” says Cutler Cleveland, a professor of Earth & environment at Boston University College of Arts & Sciences, who is working on a research project for Boston’s Green Ribbon Commission with a team at BU’s Institute for Sustainable Energy.

The city’s project is unusual, Cleveland says, because much of the emissions mitigation work by researchers around the world has so far focused on the state and national levels; the Boston project will allow researchers to “build specific models that can answer questions at the level of the city.” With the right funding and backing—the commission includes the CEOs of the region’s major utilities, hospitals, construction firms, financial institutions, and other employers; its co-chair is Boston’s mayor—he’s confident that the goal is attainable.

Which is not to say that it isn’t extremely complicated. Working on energy sustainability means finding ways to maintain or enhance 21st-century modes of living, while figuring out how a global economy and billions of people can adapt and act to mitigate those effects. That requires a synthesis of knowledge from several fields, ranging from engineering and physics to economics and public policy. To make an impact, there has to be room for both high-concept talks (the future of a seaside city, a region like New England, and the planet at large) and on-the-ground technical analysis (data collection and evaluation, statistical models, the search for solutions to specific engineering problems). It involves a series of huge topics, says Peter Fox-Penner, an energy expert who is director of the Institute for Sustainable Energy and a BU Questrom School of Business professor of the practice. The institute, based at Questrom and launched in 2016, supports and promotes faculty research, enhances course curricula across the University, and works on sustainable energy projects with the private, public, and nonprofit sectors.

“One of the things about energy is, it’s so deeply embedded in the use of our infrastructure. All of our built environment, all of the very expensive long-lived capital we use, relies on very particular energy systems,” Fox-Penner says. “And so changing all those is inherently a multidisciplinary problem. It involves different kinds of engineering, from civil to electrical to mechanical, as well as economics, as well as new business models. And urban planning. And law. You can’t turn these energy systems off.”

Re-engineering the power grid to be sustainable “is like you’re flying a plane at 20,000 feet and you’re rewiring it at the same time. And that is a pretty amazing challenge.”

It’s also a task that every organization, and every person, from a top executive to someone beginning their career, can contribute to. In fact, with major cities like Boston determined to go emissions-free (no matter what happens at the federal level), businesses may have little choice.

Paths to a Carbon-Neutral City

For Boston, cutting carbon emissions requires analyzing four areas of a city’s life: electricity usage patterns, transportation networks, building management practices, and waste disposal. By creating detailed quantitative assessments of current conditions and the policy choices available for local policymakers—whether that means new regulations, market incentives to encourage investment in new energy sources, or disincentives to discourage activities that could emit greenhouse gases—researchers can provide tools to guide decisions going forward, Cleveland says. Businesses will inevitably be impacted.

Cleveland says all cities face constraints on actions related to electrical utilities. For example, a city can set policies about municipal purchases of renewable energy, but decisions about supplies—say, replacing natural gas–fired power plants with wind turbines—is left to utilities and state and federal regulators. As for transportation, decision rights held by the regional transportation authorities that manage light rail networks, commuter trains, and buses that serve city residents and commuters limit a city’s options.

But that still leaves Boston much room for maneuvering. Congestion pricing for cars entering the city, like the United Kingdom’s capital, London, has implemented (it now costs the equivalent of about $14 to take a car into the city on a weekday), could be worth considering. Expanding bicycling infrastructure. A new system of parking fees that encourages people to use their cars less often.

And business decision-makers have their own choices to make, choices that will depend on their evaluation of the costs and benefits. Not every company is going to invest in alternative energy on a scale like Google, which in December 2016 announced that renewable wind and solar energy would power its data centers and offices around the world some time in 2017. On a more practical level, most employers can provide discounts for public transit passes and ride-sharing programs (BU does this).

Then there are buildings, which, Cleveland says, “the city has a lot of control over because they exist within the political boundaries of the city, and the city can do things such as revise building codes, and set standards for appliances, and incentivize homeowners to use less energy. They can do lots of things that can reduce building energy use.” Jacqueline Ashmore, director of research and outreach activities at the Institute for Sustainable Energy, points out that business decision-makers can evaluate a building’s energy efficiency during an office move and can consult experts to evaluate the costs and benefits of retrofitting existing facilities to reduce energy use. Third-party certifications like LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, from the United States Green Building Council) designate buildings that are resource efficient and save on energy, water, and materials used.

Getting to Work

While it’s true that much depends on industrial players such as energy utilities shifting to cleaner electricity generation sources, the choices made by individuals in their personal and work life—how much and what type of energy they use and whether they use public transportation, for example—are important.

“If you look at different rates of energy consumption across the developed world, you realize that you can have a very thrifty mind-set to energy consumption—or not,” says Ashmore. “And that really does make a difference when you multiply it by the number of people in a country such as America.”

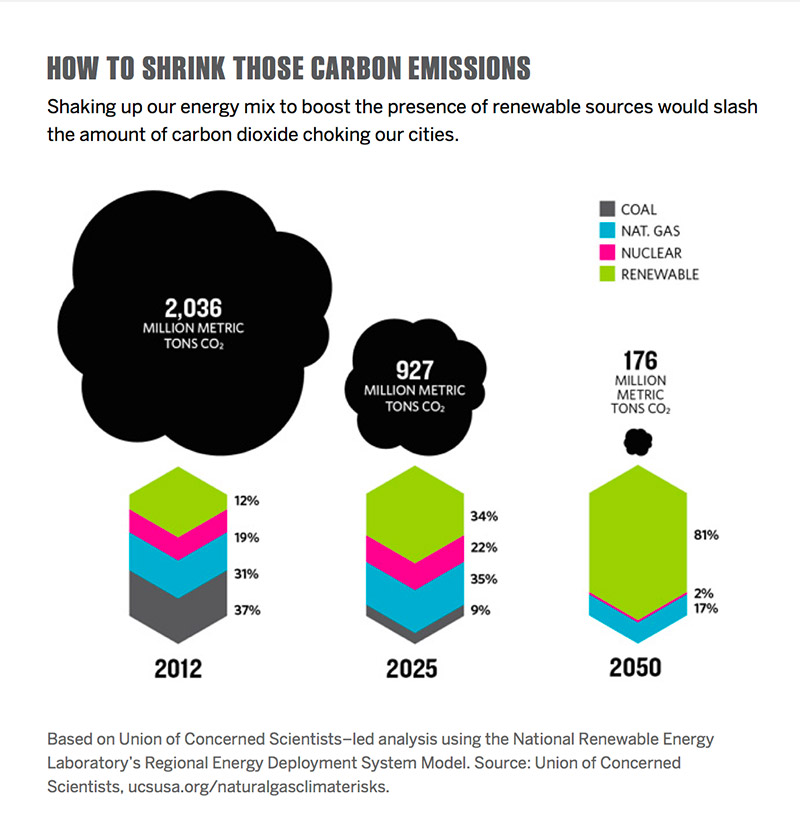

Ashmore points to data from the Union of Concerned Scientists showing per-person carbon dioxide emissions levels: the world average is 5.1 tons per person annually; the US clocks in at 21 tons. That’s three times higher than in France and two times higher than in Japan.

Experts cite a number of ways to engage these issues on the job, among them:

1. Learn from the work of others

There are models for businesses that want to cut energy usage. According to GreenBiz, a website that covers sustainability in business, retail giant Walmart has in the past decade doubled the fuel efficiency of its fleet by changing the way it loads and routes trucks, and trains drivers, saving $1 billion in the process.

Michelin, the tire manufacturer, recently adopted a zero deforestation policy for its natural rubber supplies in Southeast Asia. The multinational firm published a report explaining how it expects improved agricultural practices will preserve carbon-rich forests and reduce its production costs.

Tech leaders, whose operations have created much energy demand within computing data centers, are also working to minimize their climate impact. Apple, for instance, is looking to sell some of the renewable energy it produces in California, Nevada, and Oregon that is in excess of what the company needs. As Fox-Penner writes in an article published on the Harvard Business Review website, this move to become both a producer and consumer of energy represents an opportunity shared by many large businesses to sell power back to the grid. Apple’s move also demonstrates that efforts to cut carbon emissions can lead to new business models.

2. Pick your spots

Every company, in every industry, needs to focus on its areas of greatest impact, says Ashmore.

Transportation may be a core element of a business, or it may be a component in a supply chain or distribution system. Evaluating options for reducing emissions could mean looking at hybrid or electric vehicles. It could mean using information technology systems to retool routes that enable driving fewer miles or operating at times with less traffic (which means drivers and vehicles spend less time idling).

“Figuring out, in your industry, what is the dominant source, or what are the top three sources of carbon emissions and then understanding how you can reduce those, whether it’s a new technology, or simply a different way of doing things, those are the questions I think it’s healthy for people to be asking themselves,” Ashmore says.

In addition to reducing emissions, these activities could save money and labor.

3. Invest in talent

Paul McManus, a master lecturer at Questrom, says it’s important to remember that the sustainability field is still young, and that today’s business students are entering the workforce with concerns and knowledge to address these issues in new ways.

McManus says the students in his Strategies for Sustainable Development course enter the classroom with a host of prerequisites: finance, accounting, statistics, organizational behavior, marketing, economics, and information systems. That combination, he says, is necessary for students to gain the insights they’ll need to influence their future organizations and society.

“I’m looking to present an opportunity for students to really look at these issues in an integrative sort of way, to develop their cognitive skills related to these big and complex problems,” McManus says. “My style of teaching is somewhat aspirational, ‘Now that you understand it, what can you, as an individual, as a member of a team and organization, or a society at large, give to contribute toward positive progress in the field that we’re studying?’ ”

In the eight years he has been teaching the course, McManus has seen some students go on to careers in international development and jobs in related fields. Even those who don’t make sustainability a profession reflect on the relevance of his course for the issues they see in their lives.

“They are bringing the most up-to-date, state-of-the-art, forward-thinking ideas and understanding of the issue into industry when they graduate,” McManus says. “Like any new field, it needs to be populated with new minds, and new thinking and new theory. And that is embodied in our graduates who are going into the workforce.”

Soon to be one of those candidates is Isaac Bearg, who earned his undergraduate degree at Questrom in 2007, concentrating in finance and marketing. He returned to BU in 2015 for his MBA, focusing on sustainability issues, especially as they relate to water and energy supplies. He’s now president of the Energy Club at Questrom.

As a student in Fox-Penner’s MBA course, Bearg (BSBA’07, MBA’17) says he is learning how financing for renewable energy works, and how federal and state government policies, like tax credits and other regulations, influence business model cost structures. After a number of internships in the field, he hopes to land a sustainability-related job after graduation.

Bearg argues the issues he’s studying are not academic, but rather urgent business concerns.

“Every business needs to be considering how sustainability fits into their business model,” Bearg says. “Put simply, any time you have some sort of by-product, let’s say it’s pollution or the excess use of water, that is a cost to the business. It’s something you could be doing more efficiently. Whether you think about it as an environmental issue or not, it is a business issue.”

4. Collaborate with researchers

Institutions, including BU, offer businesses the chance to explore sustainability themes common to industry and to delve into specific projects with researchers from a range of disciplines. For its part, the Institute for Sustainable Energy is assembling an industry council for annual briefings starting in 2017. “We’ll really be looking to help those companies understand not just what’s right in front of them, in terms of changes in the landscape, but what’s just over the horizon,” Ashmore says, adding that these events will include experts from Questrom and the broader BU community, as well as leaders from outside the University.

All of the institute’s research projects, including developing models for Boston’s carbon emissions reduction program, involve experts from both inside and outside Questrom’s faculty. A recent report for Massachusetts lawmakers by consultants at The Brattle Group, for example, included work by Fox-Penner and other BU experts, who recommended ways the state could expand its renewable energy supply; several of the recommendations made it into the legislation enacted in August 2016.

“Regulators are increasingly saying, look, here is something that needs to be addressed and many utilities are experiencing those kinds of pressures. The business model of paying by the kilowatt hour is simply going to break down, and the utilities need to be thinking hard about new paradigms.” –Jacqueline Ashmore

Another multiyear project delves into the energy industry with the goal of helping Chicago-based Commonwealth Edison examine new business models for the utility industry. Ashmore says this research analyzes a future in which electric utilities won’t rely solely on charging customers according to their usage patterns, as regulators push for renewable energy sources and more sources of supply (like rooftop solar panels and wind farms) come online. Instead, utilities will turn to other means of revenue, such as services to manage energy more efficiently for both homeowners (say, by automatically running washing machines late at night instead of during the day) and business customers (by offering lower energy prices at off-peak times).

In this case, Ashmore says, researchers “are working together to define what new market models Commonwealth Edison can pilot and test and then assess as future ways of operating. That involves defining what services they want to provide, how they would price them, and understanding all the issues around market volume that tie in with pricing that’s going to make a particular approach viable or not. It’s a fascinating project.”

It’s also urgent. The regulatory climate in many states has been pushing utilities to move away from electric plants powered by fossil fuels, Ashmore says.

“Regulators are increasingly saying, look, here is something that needs to be addressed and many utilities are experiencing those kinds of pressures,” she says. “The business model of paying by the kilowatt hour is simply going to break down, and the utilities need to be thinking hard about new paradigms.”

The Opening Step

While putting a company, or a city, or the planet on a sustainable energy course can seem like it’s an inconceivably large idea, there are many footholds to step into.

“These are huge topics,” says Fox-Penner, “but we have something to contribute. One of the first things you have to do when you work on a topic that big and that important is you have to carefully evaluate specifically what you can contribute to having a positive impact on that huge, huge issue. That is the first step, I think, in doing good and important work.”

The Trump Factor

President Donald J. Trump entered office after alleging during the 2016 campaign that global warming is a hoax. In December, he announced his pick for EPA administrator was Scott Pruitt, the Oklahoma attorney general who spearheaded efforts to challenge President Barack Obama’s climate change policies in court.

One sure thing about the election result: it created uncertainty and concern about the direction of federal climate change policy among environmentalists and those researching the future of energy policy and sustainable development. That was certainly the case among those working with the Institute for Sustainable Energy at Questrom. (Interestingly, one of the institute’s research projects was working with the BU Center for Finance, Law & Policy to prepare a set of recommended actions the new administration could take to promote environmental sustainability.)

At the same time, experts from BU noted that sustainability work goes beyond what happens inside the Beltway.

“There is monumental, hugely impactful work that can be done by businesses, individuals, state and local agencies, and thousands of good NGOs,” says Peter Fox-Penner, director of the Institute for Sustainable Energy. “All of these groups are now redoubling their plans and efforts. The bottom line is that there is more to do now, and more value to what we do, than ever.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.