The Future According to Google

COM alum helps pioneer virtual reality technology for a world giant

On a weekend in November 2015, more than one million New York Times print subscribers received something extra with their paper: a small, flattened cardboard box.

The box was Google Cardboard, a $20 viewer that brings immersive virtual reality (VR) to Android and iPhone users. Folded according to directions, fitted with the provided plastic lenses, and attached to a smartphone screen, Cardboard allowed subscribers to watch The Displaced, the newspaper’s VR film about refugees, the first in a series of VR films from the Times and the VR film company Vrse. Cardboard offers a 3-D, 360-degree viewing experience. Viewers feel as though they are inches away from the refugees in the video—bicycling through a war-ravaged Ukrainian village, gliding in a small boat through the swamps of South Sudan, and traveling in the bed of a truck to a settlement in Lebanon. In one scene, watchers appear to be standing in a crowd of Sudanese refugees in a field. An engine roars. Looking up, they see a plane pass overhead. Bags of food aid fall like rain, and refugees rush to retrieve them.

While giving Times readers an intimate look at the news, Cardboard also offered a glimpse into the future of VR—an industry forecasted to reach a value of $70 billion by 2020.

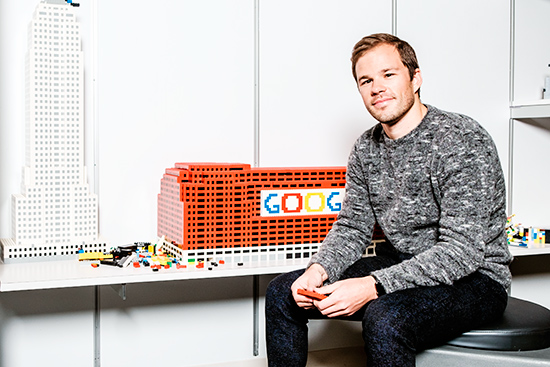

Google wants to play a leading role in VR through technologies such as Cardboard, which was released in 2014. And it’s part of Nooka Jones’ job to figure out how to make that happen. Jones (COM’10) is marketing manager and team lead at Google Creative Lab, a think tank in the company’s marketing division. His job includes coming up with ideas and names for new products, conducting marketing exercises to inspire engineers’ development of Google technologies, and identifying emerging industries for the company to work in.

Jones’ latest project is Jump, a three-part technology representing a big step forward in VR filmmaking. The first part is a rig, about 11.6 inches in diameter, of 16 cameras arranged in a circle that enables users to shoot VR video. Jump also includes software that puts the footage together in high resolution, and a player for viewing (YouTube currently hosts the videos). Part of the reason there hasn’t been much VR content for consumers until now is that filmmakers have had to cobble together their own VR rigs. Jump is expected to make VR filmmaking easier and more widespread. Jones says his team’s involvement in Jump touches on areas such as branding and communication, product design and user experience. They created the “bumper”—the brand tag (like the MGM lion, he says) that precedes every Jump film—and helped come up with the name Jump.

“It’s very early on, and there are only some exclusive partners that will have Jump for a bit, but we’re really excited about it,” says the 28-year-old Jones, whom Forbes named one of 30 Under 30 in marketing and advertising in 2015. “I think it shows huge potential in where this industry is going.”

Marketing products that don’t yet exist

The Creative Lab, based primarily in New York City, is critical to the success of what Forbes ranked in 2015 as the third most valuable brand in the world, behind only Apple and Microsoft. “We’re marketers and storytellers and filmmakers and user-experience designers,” says Jones of the lab staff, “and we use all that knowledge to shape the way a product should be talked about.”

In other words, it is essentially a marketing firm and a research and development lab rolled into one. Some of its work falls under typical branding and marketing, such as making Google TV spots and contributing to the latest company logo change. But the lab also works with designers and engineers to help create and shape new offerings, examining questions like, Where is the connected home going? What will be the future of our phones? What will the future be like if we have driverless cars? Frequently, says Jones, Google engineers ask his team for help presenting a new technology to the public. “They’ll say, ‘If you had this technology, what would you do with it? How would you showcase its potential to the world?’” says Jones. “That’s something I’ve been lucky to have been able to do in the context of both Cardboard and Jump.”

When Google Glass was in the works, engineers asked the Creative Lab for ideas on how the wearable technology might be used. The lab created an ad as if Glass were already on the market and released it to the public, showing how a person could use the product in everyday life. And shortly after Jones arrived at Google in 2013, his team made an internal vision video “full of different product ideas and principles on how you could think about computers reimagined for kids. It really blew the lid off a lot of things here,” he says. The lab later helped design some of the as-yet-undisclosed products.

All this work is part of what he calls “internal motivation” for the company—helping Google recognize and achieve the long-term potential of its products. “You have this great thing,” he’ll say to colleagues who ask his team for feedback on what they’re creating. “Here’s what it can be in two to three years. Here’s your North Star to guide you towards that.”

His work isn’t just visionary; he’s also something of a project manager for initiatives such as VR and kid-friendly products. He calls it “the business smarts” of a project. That includes determining what work his team does (and how quickly), how to pitch to stakeholders and get funding, and how a project connects to other Google initiatives. “I like to sit in with a lot of the designers and creative folks and actually think through what we’re making,” says Jones, who was previously a producer and product strategist at the digital agency Big Spaceship. “If you know what you’re making better, you’re able to position it better for the people who need to be involved or who are going to provide you money or give you the go-ahead to launch.”

Grasping a product’s design—and even helping to shape it—also helps him determine a product’s value and how to convey it to the public. “I think about the way the product feels, and what that makes you think about the product and the company at large,” he says. “Google Photos is a great example of this. At its simplest, it’s a never-ending storage box for all your life’s memories. When you communicate the product value that way, it’s so easy to understand what the benefit is, why I would need it, and the change it will bring to my life by using it.”

Virtual reality takeoff

Google has a reputation for becoming an indispensable part of consumers’ lives; its search engine and online mapping service are the most popular in the world. Jones needs to figure out how to make Google a star player in VR, too. The market is already getting crowded with products targeting a broad array of fields. At the top end of the market, VR viewers, gloves, and other implements help surgeons train for operations and immerse gamers in fantasy worlds. At the budget end, VR mobile apps that work with Cardboard allow users to fight the Dark Side in Star Wars, tour the solar system through Titans of Space, or take 360-degree VR photos. And Cardboard is helping news outlets tell stories in a new way. In addition to the Times, outlets such as ABC, Vice, and the Associated Press have released virtual reality stories.

“In the ’90s there was a big spring to make VR possible, and even in the ’70s and ’80s there were people dabbling in it, but it feels like now there’s a new sort of energy behind the whole industry,” Jones says. Google faces competition from companies that include Oculus, Sony, and Microsoft, which will release VR headsets in 2016. He attributes the new push for VR to factors such as advanced technology (better processing power, displays, and content)—and a particular tipping point in 2014. “Facebook buying Oculus, that was the big switch, I think, where everyone was like, ‘Oh shoot, we’re going to all race for this now,’” he says. “And that’s really exciting. It’s a good competitive energy to have.”

Figuring out Google’s role in the burgeoning industry requires Jones to test the latest gadgets and think about what the general user is looking for. He asks himself, “What would I want? What’s the thing that my mom would want? What’s the thing that my brothers could get excited about? That’s where I always start my thinking.”

In addition to relying on instinct when brainstorming for Google, Jones and his team conduct surveys and user testing to get answers to questions like, How does this technology benefit someone’s life? How does it bring them joy? If they use it, how do they talk about it to their friends, their family?

“Grounding yourself in laymen’s thinking helps get you out of the tech bubble,” Jones says, and “helps engineers think about products more the way consumers do.” Often that means doing branding or marketing exercises to help guide engineers, as with the prerelease ad for Google Glass: “Not creating a full campaign,” he says, “but giving a sneak peek of what a product might look like, how we might talk about it, and how we might release it to the world.”

Julie Butters can be reached at jbutters@bu.edu.

A version of this article appeared in the spring 2016 edition of COMtalk.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.