The Revolution Will Not Be Televised

Why are TV execs excited about the popularity of streaming technology?

The availability of streaming services makes some consumers question the necessity of their cable subscription. Studies show that customers have access to 200 channels, but use only about 17. Photo by Kelly Davidson

It was 2013, but Chuck Saftler’s head was in 2020. If he didn’t get creative, the FX exec realized, the deal he was close to cutting could prove a bust. He was not about to buy traditional airing rights to every episode of The Simpsons, as well as those to come, only to have the Netflixes of the world cannibalize the arrangement by snagging on-demand rights a few years later. So, Saftler says, he asked Simpsons creator Matt Groening and others at the show’s production company, Gracie Films: would they grant FX exclusive video-on-demand rights, too? The answer was yes—on one condition.

“They asked that we not take 552 episodes and just throw them into a generic, on-demand folder,” says Saftler (COM’85), president of program strategy and chief operating officer for FX Networks. They wanted “a curated experience, and something that captures the spirit and history of The Simpsons.” Saftler made his pitch: what if FX built a website and mobile app, exclusive to the network’s subscribers, based on Simpsons World, the show’s 1,200-page episode guide? Gracie agreed, and Saftler got his deal.

The FX Simpsons deal and app is one example of the kind of innovative approach to content video creators and providers are taking to keep pace with shifting viewing habits. It’s also an example of how streaming technology is changing the definition of TV. “We now live in a world where every device is a television,” BTIG media and technology analyst Richard Greenfield told the New Yorker. Television viewing schedules, he says, are mostly worthless. “TV is just becoming video.”

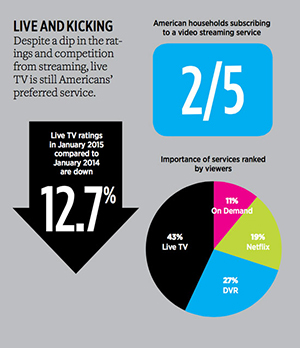

The US pay-TV market is losing subscribers. The 13 largest providers lost about 125,000 customers in 2014, although that’s small potatoes compared to the more than 95 million still on board. The more concerning drop is in viewing: Nomura Research notes that total live TV ratings for major cable networks in January 2015 were 12.7 percent less than in January 2014. Viewership is down especially among younger audiences. Some point to streaming services like Netflix, Amazon Instant Video, and Hulu as the reason. According to Nielsen figures released in March 2015, roughly two in five American households subscribe to a video streaming service.

It was only a matter of time before the growing pains evident in the relationship between internet and print made its way to TV. “Television, partly because its files are so much larger and tougher to download, was insulated for a time, and had the benefit of having seen what happens when you sit still—you get run over,” wrote the late New York Times media columnist David Carr, COM’s first Andrew R. Lack Professor of Journalism. Netflix is the threat to watch out for. “We are to cable networks as cable networks were to broadcast networks,” Netflix CEO Reed Hastings said in 2014. Having transformed itself from a DVD rental service into a streaming superpower, and with House of Cards, a production house, Netflix “pointed a way forward by not only establishing that programming could be reliably delivered over the web, but showing that consumers were more than ready to make the leap,” Carr wrote.

Netflix “pointed a way forward by not only establishing that programming could be reliably delivered over the web, but showing that consumers were more than ready to make the leap.” —David Carr

But the popularity of streaming services like Netflix doesn’t mean viewers have turned their back on more traditional viewing. According to Saftler, 25 million unique viewers tuned in to the 12-day Simpsons marathon in 2014 that led up to the release of the Simpsons World app. In a 2014 study by Leichtman Research Group, 43 percent of viewers ranked live TV as more important than DVR (27 percent), Netflix (19 percent), and on demand (11 percent).

Nor does everyone perceive streaming’s popularity as bad for traditional television. When networks give streaming services access to their shows, they get licensing revenue. Having a presence on a streaming service can also increase brand visibility and drive viewers back to TV. FX has an arrangement with Hulu, which Saftler says is “very supportive of our brand,” adding that “we hope when somebody is able to binge and discover previous seasons on that platform, it returns them to that main network, where they’ll watch new seasons when they come up on FX.”

Streaming also gives viewers more opportunities to watch content. “Everyone keeps talking about how TV viewership numbers are going down,” says CBS Networks’ Amy Young (CGS’00, COM’02), “but these new connections and relationships and technologies are allowing people to watch more.” The vice president of video on demand and content distribution and network sales points to the premiere episode of its show Scorpion. “Average viewership jumps 88 percent when you look at the full 35-day multiplatform window versus live and same-day viewership,” says Young. “It’s just a matter of figuring out how we roll services out effectively to meet those demands, how we measure it, how we monitor it and how we advertise it. It’s a really big opportunity right now, one that changes every day.”

Networks strike back

Broadcast networks have to be especially innovative: their audience is a third of what it was in the late ’70s. Some are launching their own streaming services to cash in. In October 2014, CBS became the first to launch a subscription-based service, CBS All Access. In April 2015, HBO made headlines with its stand-alone streaming service, HBO Now, enabling viewers to watch shows like Game of Thrones for $14.99 a month without a cable subscription.

With CBS All Access, the network was aiming in part to reach “the younger demographics, who watch television in a completely different way than our older audiences,” says Young. For $5.99 a month, it offers more than 7,500 CBS episodes on demand, current shows like The Big Bang Theory as well as ad-free old favorites like Star Trek. It also has bonus online content for broadcast events, like a backstage look at the Grammy Awards, and content an ad-based model wouldn’t support on traditional TV, like a 24/7 live feed of the Big Brother house. As of May 2015, 64 percent of US households can also use All Access to watch most CBS programs live, thanks in part to deals with CBS affiliate groups.

Catering to viewers while staying on good terms with affiliates and distributors can be a delicate balance, Young says, but CBS All Access is targeted toward “superfans, those folks who maybe don’t have a cable or satellite subscription. It really worked for us in a way that we don’t feel jeopardized our relationships with our more traditional partners.” Multiplatform offerings also give CBS and clients an opportunity to collect more data on viewers and find new ways to engage with them.

Deborah Jaramillo, a College of Communication assistant professor of film and television, says All Access is a smart way for CBS to stay relevant, especially given societal amnesia about the free broadcast model. “My students have a difficult time understanding that there is such a thing as over-the-air television, because they grew up having access to cable,” she says.

The availability of streaming services, along with streaming players like Roku and Google Chromecast that bring internet content to your TV, makes some consumers question the necessity of their cable subscription. The increasing cost of that service, roughly $99 a month, doesn’t help cable’s cause, especially when, as NBC reports, studies show that customers have access to 200 channels, but use only about 17. Cathy Perron (COM’99), a COM associate professor of film and television, predicts more “cord-cutters” each year. “People will take a look at what their budget is for media consumption,” she says, “and I think they will allocate it to a lot of different services.”

Cable and satellite providers are taking notice, offering “skinny bundles” to give viewers more flexibility over what they pay for. Not all cord-cutters—or “cord-nevers,” those who have never paid for cable—get a better deal. Dish Network’s SlingTV, for instance, can be used on one device at a time—not necessarily the best option for a large family. And for streaming consumers, subscribing to multiple services adds up. Finally, broadband providers could jack up internet access fees to compensate for lost cable revenue.

Mad about mobile

A few years back, Brian Bedol (COM’80) was sharing a meal with his business partner Ken Lerer, and they began discussing how media ventures they’d launched—for Lerer, the Huffington Post, and for Bedol, Classic Sports Network (now ESPN Classic)—might have been different if they were launching them in the present. “We decided to start a company that was focused on building video media brands over the internet,” Bedol says.

That company, Bedrocket, is primarily focused on “shareable, stackable, short-form entertainment,” from stand-up comedy routines to highlights from Paris Fashion Week, “that is designed to be consumed primarily in mobile and is for the most part ad-supported,” Bedol says. Bedrocket’s properties include Network A, which bills itself as “the world’s fastest growing action sports network,” Flama, which offers programming “with a Latin twist,” and KickTV, a YouTube soccer network that Major League Soccer has an ownership stake in. KickTV, which Bedrocket built from the ground up, now has more than a million subscribers.

The company’s calling card is its video platform Boxxspring. Just as WordPress provided a text-publishing vehicle for the Huffington Post, he says, Boxxspring gives media companies and brands an infrastructure for video publishing. Among its capabilities are player technology, advertising, cross-platform analytics, and distribution to native video players on social media platforms. Bedrocket’s services also include original programming production and support for advertising and distribution.

“Everyone keeps talking about how [TV] viewership numbers are going down, but these new connections and relationships and technologies are allowing people to watch more.” —Amy Young (CGS’00, COM’02), CBS Networks

Bedrocket’s tagline is “media for the post-cable generation.” Bedol says that’s not a prediction of cable’s demise, but a commentary on the proliferation of on-demand video consumption. “It is up to the audience to determine what they want to see and up to creators to make stuff that audiences want to see,” he says. “Ultimately it is a direct relationship between the creator and the audience, and that part of it is liberating,” (Bedol doesn’t have to wait for Nielsen ratings to gauge success) “but it is also an economically much more challenging model, because you don’t have the luxury or the foundation of subscriber revenue to build an audience like you do with cable.”

Research from Bedrocket and other sources shows the company is on trend by focusing on mobile distribution. According to the research company Millward Brown, consumers in most countries, including the United States, spend more time on their smartphones than on their TVs. As for consumption of Bedrocket’s content, says Bedol, “over the past two years, we have seen content consumption patterns shift from probably 70 percent over the internet on some sort of computer device to 60 to 70 percent on mobile.” The introduction of video on Facebook, he says, has also been a game changer. “It is no longer a company telling me what maybe I will want to watch; it is my friends, who know me so much better, saying, ‘Hey, you have got to check this out!’”

Whatever revenue model or platform the players in this new television landscape choose, they all recognize that original programming is crucial to their success. As early as 2011, Netflix’s Hastings said HBO, not another streaming service, was his main rival. Netflix is expected to spend as much as $5 billion on original programming in 2016. “Our originals cost us less money, relative to our viewing metrics, than most of our licensed content, much of which is known and created by the top studios,” he wrote in a January 2014 letter to shareholders.

The real challenge, says Perron, is finding the budget to produce enough quality content to satisfy viewers without raising subscription costs. There’s also still something to be said for delayed gratification—Netflix releases entire seasons at once—even among millennials. Issa Kenyatta (COM’16) says some of his friends will binge-watch House of Cards over a weekend, but he prefers to pace his viewing. “There’s just something about the anticipation of waiting another week for your program to broadcast that makes it that much more exciting.”

With viewers increasingly tuning in to social media and streaming services for new, original content, where does that leave traditional TV? Hastings has said that the future of the medium is in airing live events, such as the Olympics and the Super Bowl, and Jaramillo believes he’s onto something. She says television’s future could be its past: all TV was originally live. The value of broadcasting is “to reach the most people at the same time with something that’s happening live,” she says. Award shows, national emergencies, the news, and popular live musicals like NBC’s The Sound of Music are “events and genres that we need to take into account as television moves forward.”

Change is inevitable, but “television is a set of behaviors and practices that has been changing since the late 1940s,” says Jaramillo. “It just keeps changing, it keeps adapting, it keeps meeting these challenges.”

Julie Butters can be reached at jbutters@bu.edu.

A version of this article originally appeared in the fall 2015 edition of COMtalk.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.