SPH Dean’s Symposium Tackles Health Rights of Prisoners, the Public

Experts discuss torture, solitary confinement, mental health

Juan E. Méndez, United Nations special rapporteur on torture, discussed human rights issues facing prisoners, like force-feeding, sexual assault, and solitary confinement, at Wednesday’s SPH Dean’s Symposium. Photo by Jackie Ricciardi

In 2015, the US Senate Intelligence Committee released a summary report highly critical of the Central Intelligence Agency’s Rendition, Detention and Interrogation Program. The report concluded that high-level officials promoted, encouraged, and allowed the use of torture after the September 11 terrorist attacks.

The report was “a step in the direction of truth,” said Juan E. Méndez, United Nations special rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, speaking Wednesday at the quarterly School of Public Health Dean’s Symposium, (Public) Health and Human Rights.

But, Méndez said, the United States should go further, releasing the full report, and holding those responsible accountable. “The impunity of the United States presents a big drawback in the global fight against torture,” he said. And when the subject of torture comes up in his travels to other countries, he often hears the same refrain: “If the United States does it, why can’t we?”

“Torture is absolutely prohibited in international law,” he said. “But the crime of torture continues to be relevant, unfortunately.”

Méndez and Dainius Pūras, UN special rapporteur on the right to health, were the two featured speakers at the daylong SPH symposium, which invited scholars and policy makers from across the country to discuss crucial questions: do humans have a right to health? And, if so, what does it entail?

“Human rights is a topic I have long felt should be animating what the School of Public Health does,” said Sandro Galea, dean of SPH, “and be at the core of the mission of public health as a discipline.”

President Franklin Roosevelt is credited with the concept of universal human rights—in his 1941 State of the Union address, known as the Four Freedoms speech, he proposed four fundamental freedoms that all humans, everywhere, are entitled to: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. The address, immortalized in a series of Norman Rockwell paintings, helped inspire the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948. The Universal Declaration “is still considered one of the most important documents on human rights,” said George Annas, a William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor and an SPH, a School of Medicine, and a School of Law professor, who chaired the symposium.

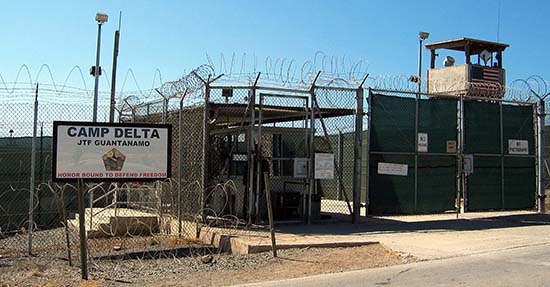

The symposium was divided into two sections: the general public’s right to health and the specific rights of prisoners. Méndez’s talk and the subsequent discussion focused on prisoners’ health rights, including access to care and freedom from torture and medical experimentation.

Sandra Crosby, an SPH and a MED associate professor and director of the Boston Medical Center Immigrant and Refugee Health Program, discussed the case of Jihad Ahmed Mujstafa Diyab, the first Guantánamo Bay hunger-striker to protest his force-feeding in court. Although the judge did not rule in Diyab’s favor, the case “illuminated the role that medical professionals played in his treatment. They were complicit,” said Crosby. Doctors punished Diyab, who was paralyzed, by taking away his wheelchair, his crutches, his underwear, and his socks. “Clinicians became caught up in the culture,” she said. “They completely lost their therapeutic relationship with the patient.”

Crosby’s case study was part of a broader discussion of the controversial and often complicated legal and ethical issues at play when human rights intersect with human health. While the panel agreed that the Diyab case clearly rose to the level of torture, much of the discussion on detention focused on fuzzier issues: is solitary confinement ever ethical? How much psychiatric care must the state provide prisoners? How much dental care? Is an overcrowded prison inhumane? And who is responsible for ensuring legal, ethical care for prisoners?

The symposium’s other session focused on the nonpunitive side of the equation: do countries owe all citizens a right to both physical and mental health? And if so, how far are states obliged to go?

“It’s not just the right to medical care, but also the right to the determinants of health,” said symposium speaker Pūras, who investigates human rights and health care through fact-finding missions worldwide. Pūras described his job as being a “spy within the health care system.” When investigating health care in Paraguay, for instance, he became frustrated visiting hospitals—“What can you see in a hospital in the capital? They have lots of good equipment”—and veered off to visit schools instead. By talking to teachers and students, he learned that reproductive education was limited and that children were anxious for more.

The right to health must go well beyond the basic needs of food, housing, clean water, and access to basic medical care, Pūras said. While applauding the progress that public health measures like vaccines and nutrition have made in reducing infant and child mortality, he argued that leaders should consider children’s “holistic development”—their intellectual, spiritual, social, and cultural growth—as well. “These things are just as important and should not be considered a luxury,” he said.

Pūras also advocates a zero tolerance for violence, including violence within families. “Violence is a public health problem,” he said. “The so-called traditional family values now in fashion are often against the rights of women and children. They hold the rights of families above the rights of people to be free from violence.”

His goal, he said, is to convince policy makers, medical doctors, and the public at large that the best vaccine is an approach combining human rights and public health. “This combination is very powerful,” he said. “If it is implemented in a sustained way, it can make new miracles.”

In his talk’s follow-up discussion, experts focused on practicalities: how can governments best implement goals, what legal framework can they use, and where do people like physicians, social workers, and citizens fit in the mix?

Panelist Sofia Gruskin, director of the University of Southern California Program on Global Health and Human Rights, said it was clear from the discussion that health is not just about medicine, but includes politics, law, economics, and social work as well. And this complexity is a good thing: “Human rights may be a framework that allows people to work together and form alliances,” Gruskin said.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.