Huntington Stages World Premiere of Craig Lucas Play

New drama by CFA alum features both deaf and hearing actors

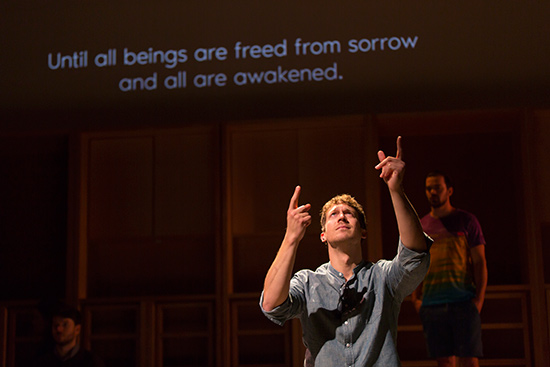

Russell Harvard plays Knox, a young man who is deaf, gay, and an alcoholic, in I Was Most Alive with You. Photo by T. Charles Erickson

When playwright Craig Lucas found himself facing a particularly dark moment in his life seven years ago, a friend suggested he read the Book of Job, the famous Biblical treatise that explores why righteous people suffer.

At the time, Lucas (CFA’73) was approaching 60 and had begun to grapple with a series of big questions: What am I doing? What do I want? What matters? As he read the story of Job, he says, “I began to think about humility and our place in the world and what we can rightly claim as things that lie within our power and things that are beyond our power.” After further readings, including Erik Erikson’s writings on old age, Lucas set out to write a play that would address “what happens when human beings are confronted with what the fates hand them.”

A three-time Tony award nominee, for his original play Prelude to a Kiss and for best book of a musical for The Light in the Piazza and An American in Paris, Lucas began to think about a situation that might challenge a family in a way that was, in his word, “tectonic.”

“I was looking at something that could happen to a family that would be so deeply challenging that it would not just mean the loss of one thing, but the loss of levels of things,” he says. The result is I Was Most Alive with You, a drama that mixes tragedy with comedy. Its world premiere by the Huntington Theatre Company is running through June 26 at the Boston Center for the Arts Calderwood Pavilion.

The play’s action starts on Thanksgiving Day. The protagonist, a young man named Knox, gathers with friends and family and gives thanks for three things that he had previously thought were curses, but has come to see as gifts: being deaf, being gay, and being an alcoholic. “Knox is someone who everyone likes, because he has gotten through some of life’s bigger knocks and he maintains a joyful demeanor and approach and he is loved by his students,” says Lucas.

In the aftermath of a terrible tragedy that befalls Knox later that night, his family and friends struggle to bring him back from the brink of despair. The play, the author says, explores “how we go on in the face of seemingly impossible odds and what is it about life that makes us hold on when our heart is shattered and heavy.”

The idea of making the lead character deaf occurred after Lucas saw Nina Raine’s drama Tribes off-Broadway, with actor Russell Harvard playing a deaf son who brings a young woman who’s slowly losing her hearing home to his comically dysfunctional family. He had previously seen Harvard in the Oscar-winning film There Will Be Blood, and the actor had made an indelible impression.

“There are a handful of actors in America who know that less is more,” Lucas says. “I thought, man, oh man, I want to work with him.” Harvard, who has workshopped the play over several years, stars in the Huntington production.

The cast of I Was Most Alive with You includes both deaf and hearing actors. The play is performed in two languages, English and ASL, with four shadow interpreters appearing on stage, moving in close proximity to the actors they’re interpreting. One of the four is Christopher Robinson, coordinator of outreach and training in BU’s Disability Services office.

But, Lucas say, this isn’t a case of two casts performing the same role simultaneously.

“I see one person playing the role, with the signer or shadow interpreter playing an aspect of the character’s inner psychic life,” he says. To underscore that, the two young white male characters are signed by an African American, the late-middle-age father is signed by the youngest shadow interpreter, and the white female character is signed by an Asian. The actors signing are referred to as shadow interpreters, the playwright says, “because they are literally in the shadows” on the stage.

There’s a very interesting dynamic at work, because at any moment there is one actor signing and another speaking, says Lucas. “They’re very different languages,” he notes. “They have a different grammar, but also English is about a lot of masking and nuance and hiding, and ASL is not about hiding. It’s very much about putting it out there, and the face is the storytelling device that ties together the signs. So ASL is almost two languages: the signs and how the face and body language knit the signs together….There’s something about ASL that has this other music going on, which is completely visual, like hieroglyphics.”

The playwright incorporated ASL into his 1983 play Reckless, but he says that despite studying the language for a number of years, it still evades him. In creating I Was Most Alive with You, he relied on a network of collaborators in the deaf community. Deaf actor Sabrina Dennison provides the artistic sign language direction for the production.

“I wrote the play in English and then I began to elicit the massive aid of people who speak ASL,” Lucas says. “I basically said, ‘Tell me what I got wrong. I do not need to be right about what I wrote. What I need to is to hear what you feel.’” He says that more than once he was disabused of things “that I thought could be achieved in certain ways,” as the piece developed.

The play’s tragedy is leavened by moments of genuine comedy. “In my experience, when people are faced with cataclysmic events, often they somehow survive through seizing hold of things,” he says. “In my life, whenever someone is dying, there is always somebody in the next bed watching Let’s Make a Deal.”

For this production, Lucas is doing double duty as playwright and director, but he says he didn’t set out to direct the play, even though he has directed productions of some of his earlier work, as well as the films The Dying Gaul and Birds of America. He says in some ways the play’s complex nature makes it easier to direct. “To simply sort out the Thanksgiving scene with one deaf person, one hard-of-hearing person, one person who signs really well, one person who signs sort of okay, a bunch of people who kind-of, sort-of sign, somebody who is resolutely refusing to sign, somebody who won’t wear their implant—it’s madness,” he says.

Despite Lucas’ long involvement with the play, he, Dennison, and others involved in the production were still tweaking a couple of weeks before the show’s opening. During a recent rehearsal of the Thanksgiving dinner scene, it became apparent that the sequence—at 25 pages, the longest in the play—wasn’t working. “None of us knew what to do,” Lucas says. “Because it’s such a long sequence, and everyone is seated in it, we literally began moving chairs around. We kept going, ‘Hey, what if mom was actually up on the higher level and what if they were in profile?’” It took hours before they were satisfied that they had a workable solution.

Lucas, whose first play was staged 35 years ago and whose other plays include Blue Window, The Dying Gaul, and Prayer for My Enemy, says I Was Most Alive with You marks something of a departure for him.

“I have noticed with this play that I am less interested in being clever….I am learning very late that the music of something and the underground river of a story need not be in words. They can be in the design,” he says. “I am noticing with this play in particular that the dramatic gesture is not in the words. It exists on a much deeper level. It is the skeleton, and the skeleton is the thing that you really have to protect.”

Asked if he could have imagined writing this play any earlier in his career, Lucas answers with a flat no, adding that now that the play is being staged, “I cannot imagine that I wrote it at all. There is something that happens for me where writing is more like an act of dictation. When you are working well, you are kind of there as a conduit for something that is coming from your unconscious and coming from a deeper force. I am not clever enough to have written this play. But I lived through things that allowed me to sit there in the room and write down what appeared.”

The Huntington Theatre Company production of I Was Most Alive with You is running at the Boston Center for the Arts Calderwood Pavilion’s Wimberley Theatre, 527 Tremont St., Boston, through June 26. Purchase tickets online, by phone at 617-266-0800, or in person at the Calderwood Pavilion box office or the BU Theatre box office, 264 Huntington Ave. Patrons 35 and younger may purchase $30 tickets (ID required) for any production, and there is a $5 discount for seniors. Military personnel can purchase tickets for $20 with promo code MILITARY, and student rush tickets are available for $20 (valid ID required). Members of the BU community get $10 off (ID required). Call 617-266-0800 for more information. Follow the Huntington Theatre Company on Twitter at @huntington.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.