DIGNITY: Tribes in Transition

New BUAG show highlights plight of indigenous peoples

Woman with Pipe, Haiti, 1983. Photo by Dana Gluckstein

Dana Gluckstein was launching a successful career as a commercial photographer when a spur-of-the-moment decision changed her life. After shooting an annual report for a corporate client in 1983 in Puerto Rico, she decided to hop a flight to Haiti to shoot portraits of local residents.

When she came upon a Haitian woman smoking a pipe, Gluckstein was instantly drawn to her, but nearly talked herself out of taking the photo.

“It was very late, almost nighttime, hardly any light, and my intellect was chattering away saying, this is going to be a terrible image, you’re never going to get it, it’s not going to be sharp,” she recalls. “But something in me was so moved by her presence that I did it.”

She didn’t know it at the time, but Gluckstein had sparked a passion that would dominate her life: photographing the indigenous peoples who comprise 6 percent of the world’s population. Since then, she has crisscrossed the globe, often at her own expense, to record the lives of the Goba in Zambia, the Maasai in Kenya, the Quechua in Peru, and peoples in Bhutan, Botswana, Bali, and Mexico, as well as native Hawaiians, members of the Navajo tribe in Arizona, and the Campbell River Indian Band in Canada.

Some 60 of Gluckstein’s iconic images are on view in an extraordinary show at the Boston University Art Gallery (BUAG) at the Stone Gallery through March 29. DIGNITY: Tribes in Transition captures men, women, and children around the globe whose way of life is threatened by a mix of corporate, governmental, and missionary interests and by what Gluckstein calls the “encroachment of capitalism.” The images pay tribute to people who in her words are “fighting for their lands, their traditions, their languages, and their very lives.”

After that 1983 trip to Haiti, Gluckstein attended a conference of global and spiritual leaders in Oxford, England, that included Mikhail Gorbachev, the Dalai Lama. The experience, she says, was eye-opening and strengthened her belief in the fundamental concept of unity, the idea that “we are all really one,” affirming her belief that artists are the seeds of change, that art can “open hearts and make a difference.”

“If I’m able to capture in each image that unique soul, that essence, that dignity, and the viewer is able to feel it as well,” she says, “then we transcend. I want each portrait to have that moment of transcendence, where you feel that connection.”

Gluckstein pursues her passion between commercial jobs. She tries to travel to places that are “still deeply connected to the earth and these traditional values and customs,” but she’s often shocked when she arrives at a destination because “my mental image or expectation of what I thought I should find wasn’t there.”

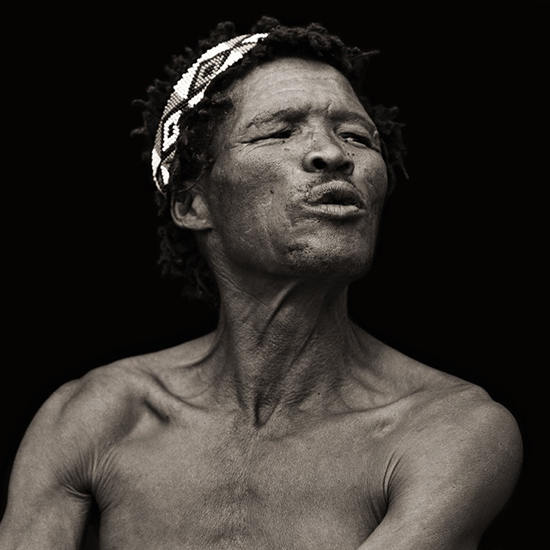

Examples of this abound as she’s traveled around the world. On a trip to Botswana in 2009, she met a San Bushmen hunter living in a squalid government resettlement camp in the remote outback. “The San have been forcibly removed to these camps because of corporate diamond mining concessions on their ancestral and sacred lands,” says Gluckstein. “Companies like DeBeers work in association with the government and do not share the profits with the San.” As a result, “the most ancient, gentle people still in existence on the planet” now live in dire poverty and have been plagued by AIDS and alcoholism. The hunter she photographed expressed despair that he could no longer feed his people, because the government requires them to purchase hunting licenses, which they cannot afford. “This place and the sorrow of the people broke my heart,” she says.

Similarly, when she visited Zambia in 2007, she met two teenage Goba boys in a remote village along the Zambezi River. They watched as she photographed a Goba elder with nothing but a tattered black cloth to cover his emaciated shoulders, and after the shoot, Gluckstein says, the boys ran home and returned with “crude cardboard masks they had just constructed to replicate their imagined version of traditional masks.” The tribe had been completely stripped of their authentic heritage, she says.

And in Bhutan in 2010, Gluckstein was shooting a religious festival when she spotted a young boy dressed in his traditional gho attire holding a toy rifle. During the festival, traditional chants and dances were punctuated by young boys playing “shoot ’em up” in the monastery courtyard. The arrival of television in 2000, she says, has introduced an onslaught of Bollywood and Hollywood images that threaten this ancient, mystical Himalayan culture.

“I would often arrive at a location and think, I should leave, this isn’t what I thought I was going to portray. Then I would knock myself on the head and say, this is the story, Dana, just what you’re seeing: there’s a collision of culture happening on the planet.”

Despite those grim scenarios, Gluckstein sees pockets of hope. One of the exhibition’s most striking photos is a Campbell River Indian Band high school girl dressed in a full-length robe. “This girl practices the traditional sacred dances of her First Nation Band,” says Gluckstein. “There’s been a renaissance of young people learning their traditions without fear of being humiliated or needing to assimilate. They are learning to walk proudly as keepers of sacred wisdom and still be teenagers in the contemporary world, and this is happening throughout the world.” For the photographer, such action represents “a profound act of empowerment for indigenous peoples rising from the ashes of destruction and despair.”

She also points to the successful efforts by native Hawaiians to hold onto their language and culture. One of her most unforgettable images is of a young Hawaiian chanter who “depicts the cultural renaissance of native Hawaiians who are seeking to heal the centuries of cultural erosion and loss of identity that followed the theft of their program.” Today, she notes, many native Hawaiian children are attending Hawaiian cultural immersion programs, where they learn to speak their once forbidden language and dance the traditional hula. The photograph of the chanter—a personal favorite of Gluckstein’s—“reflects this history and the hope for the future.”

There is a magisterial quality to the exhibition’s 60 portraits. Gluckstein uses a Hasselblad, a bulky, cumbersome camera, to capture her iconic black-and-white images. “For 30 years, this camera has never failed me,” she says. “Its slow, deliberate, weighty design and high-resolution square negative make me feel as if I could render the eternal in a photograph. I still wait reverentially for the film to develop and to transport me into the mystical realm of images.” There is something almost religious for her as she develops an image: “It becomes a ritual, a holy act.”

Gluckstein’s portraits are notable for the natural light that suffuses them, part of what she calls “painting with light.” As a high school and later a Stanford student, she studied painting and drawing. She majored in psychology and minored in art in college, but became captivated by light and began picking up a camera—an Instamatic—to capture the light during a junior year abroad.

While Gluckstein’s work is not overtly political, she has used her project to draw attention to the plight of indigenous peoples. In 2010, she published 90 photographs (many of them in the BUAG show) in the book DIGNITY: In Honor of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (powerHouse Books). Publication coincided with Amnesty International’s 50th anniversary, and the book included the text of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which the United States had voted against in 2007, and it appealed to people to ask the United States to adopt the Declaration. President Obama did so in 2010.

Many of the book’s photographs became part of an exhibition that traveled to Switzerland and Germany. BU is the first stop on its US tour, and visitors are invited to sign a letter addressed to the president urging him to make the Indian Health Services implement the Standardized Sexual Assault Protocols that were adopted in the Tribal Law and Order Act of 2010.

Gluckstein says she’s especially pleased to provide an opportunity for college students to learn more about the world’s indigenous peoples. And she offers some advice as they contemplate their own career path.

“I like to say to students that life is a long journey, and the excitement of the journey is not having the crystal ball and knowing exactly where you’re going, especially if you’re an artist. You’re really trying to listen deeply to your heart, your intellect, what you feel committed to, how you want to make a difference, and that takes time to emerge. Listen to what it is you want to say in the world…but don’t wait until you feel like you’re perfect. That will never happen.”

Dignity: Tribes in Transition is on view at the Boston University Art Gallery at the Stone Gallery, 855 Commonwealth Ave., through Sunday, March 29. Hours are Tuesday through Friday from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday and Sunday from 1 to 5 p.m. The exhibition is free and open to the public. By public transportation, take an MBTA Green Line B trolley to BU West. Note: The gallery will be closed for spring break, from March 7 through 16.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.