The Little Dive with a Long History

Brinks robber hangout, BoSox refuge, blizzard shelter: the Dugout at 80

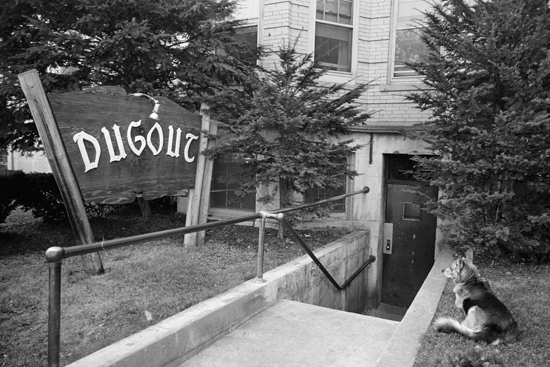

“This is a bargain basement bar,” wrote a Boston Globe reviewer of the Dugout in 1979, “and it doesn’t pretend to be anything else.” That dive-and-proud-of-it spirit persists at the Dugout today. Photo by BU Photography

What is it about the descent of a few steps that makes a bar seem special? Cheers, the old Rathskeller, the BU Pub—all in basements. Perhaps such a place feels like home, its cozy dimensions tugging at our cave-dweller roots. Beneath street level, out of sight, and away from the bustle of work, patrons feel free to loosen their neckties, share their off-the-cuff opinions, and tell off-color stories.

Or is it the thrill of the illicit? Fugitives from the law go underground, and the original dive bars were in cellars—literally underground. In a nation that once outlawed alcohol, maybe imbibers are seeking a speakeasy vibe: walking down those stairs and into a dimly lit barroom feels like an act of rebellion against an imposed morality.

Or perhaps, in the case of the Dugout Cafe, it’s a bit of both.

Some say the Dugout was a speakeasy during Prohibition. According to Boston’s Licensing Board, the Dugout’s was one of the first liquor licenses issued after the December 1933 repeal of the Volstead Act, which had established Prohibition in the United States in 1919. In the eight decades since it officially opened in 1934, the modest watering hole below 722 Commonwealth Avenue has been a haven for pro boxers, big-league ballplayers, and career criminals, as well as BU students, staffers, and professors. And the joint looks its age—the way regulars like it. Wood paneling, wobbly stools. Bud and Sam on tap. Free popcorn. Even with a few patches and updates, the Dugout has kept a timeless and comfortable quality, like a favorite old pair of jeans.

“It’s a no-baloney kind of bar,” says bartender Bob Lupo (although he doesn’t use the word “baloney”). “We don’t take credit cards, there’s no air-conditioning, if you ask for a Piña colada, I’ll probably tell you to buzz off. But it’s a relaxed sort of place. We expect you to treat it like your home—don’t leave a mess, but it’s a good place to just hang out and shoot the breeze.” (Lupo doesn’t use the words “buzz” or “breeze” either.)

For decades, the Dugout belonged to a former bootlegger who owned racehorses and managed prizefighters—a local celeb once more recognizable than Ted Williams. A man so well connected, he’s said to have swayed elections and even punched out a governor. A proprietor who, like Deadwood’s Al Swearingen, lived upstairs from his establishment, and who probably would have agreed with Swearingen that “as a base of operations, you cannot beat a farthing saloon.”

(Swearingen did not use the word “farthing.”)

Heavy hitters

Jimmy O’Keefe was born in 1904 near Kenmore Square. As a child, he played in an open field soon to be Fenway Park. In his teens, he delivered groceries from a horse-drawn wagon. Then as a young man, he opened a pharmacy that did a brisk trade in “medicinal” liquor, one of Prohibition’s many loopholes. O’Keefe parlayed that success into a small business empire, encompassing nightclubs in Boston and on Cape Cod. He hired a future math teacher, George Daly (SED’25), to keep the books for his various income streams. (Daly, who happens to have been my grandmother’s uncle, was by no means the last BU student or graduate O’Keefe would employ.)

Situated roughly halfway between Fenway Park and Braves Field (now Nickerson Field), the Dugout was especially popular with baseball fans, sportswriters, and gamblers, as well as many of the Red Sox and Braves players. Sox manager Pinky Higgins (1956–1965) reportedly fell off his stool there at least once. In his first year in Boston, Ted Williams—a rookie, sure, but a much-hyped rookie on pace to hit .327 with 31 home runs and 145 RBIs—borrowed O’Keefe’s car. A police cruiser soon pulled him over. The patrolman didn’t recognize the young driver, but demanded, “What are you doing driving Jimmy O’Keefe’s car?”

Two years after opening the Dugout, O’Keefe forayed into politics. He was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1936. The following year, he worked behind the scenes to get Maurice Tobin elected mayor of Boston; Tobin scored an upset win over the legendary James Michael Curley. By 1945, Tobin was governor of the Bay State, but when he refused to find a job for an O’Keefe friend, the disagreement devolved into fisticuffs. O’Keefe won.

Those years were stormy in general for O’Keefe. His Nantasket nightclub was firebombed in 1937. His one brief marriage ended in divorce in 1941. Days later, a brawl erupted in the Dugout that resulted in prison terms for two patrons—one a boxer, the other a convicted robber who’d been on probation. And in 1942, the Boston Health Department closed the Dugout for more than a week, part of a citywide crackdown on nightspot code violations following the tragic Cocoanut Grove fire that claimed the lives of 492 people.

Small wonder that a Boston University dean called for the Dugout’s permanent closure. William Sutcliffe was dean of the College of Business Administration (precursor to the School of Management), one of the first BU schools to move from Copley Square to what is now the Charles River Campus. In 1946, he filed a request that the city’s Licensing Board revoke the taproom’s permit “on the grounds that the place is not conducive to academic work,” the Boston Globe reported. The board held a hearing.

The Dugout’s license was renewed.

Crime of the century

Four years later, the two most notorious Dugout customers would attain that notoriety when they took part in what was then the biggest heist in American history. On January 17, 1950, Adolph “Jazz” Maffie, Joseph “Specs” O’Keefe (no relation to Jimmy), and nine other men robbed the Brink’s, Inc., armored car depot in Boston’s North End, getting away with more than $2.7 million. The meticulously planned robbery took the FBI almost seven years to solve, and it was dramatized in the 1978 film The Brink’s Job, starring Peter Falk and Peter Boyle. The stolen money has yet to be recovered.

And the crooks dreamed it up at the Dugout.

At least, that’s the story. The late Frank Kennedy, a Dugout bartender for decades, used to point to the corner booth “where the Brinks guys planned it,” says broadcaster and author Bernie Corbett (CAS’83), who also tended bar there part-time for years. And that wasn’t just Kennedy’s recollection. It is documented that Maffie and Specs O’Keefe knew Jimmy O’Keefe. Maffie even used Jimmy O’Keefe’s Restaurant, at Boylston Street and Massachusetts Avenue, as his alibi: Maffie’s wife testified that she was having dinner with him there when the robbery took place. (The jury didn’t believe her.) And a postal worker later told the Globe he remembered often seeing Maffie and his bodyguards at the Dugout.

Still, is it likely that the gang of robbers, all 11 of them, planned the complicated heist, in its entirety, in such a public place? That seems a stretch. Even if it were just Maffie and Specs who spent time at the Dugout, they surely wouldn’t want to be overheard talking shop. But Lupo points to the back room. That’s where he always heard the crooks had congregated. It would certainly be more private. Furthermore, these men spent 18 months planning the caper, the biggest of their criminal careers. It likely dominated their waking thoughts for that time. So did they discuss the job while hoisting a few at the Dugout? It’s hard to believe they didn’t.

A sportsman and a gentleman

In 1961, O’Keefe himself was arrested, at the Dugout. An undercover vice detective overheard him placing bets over the phone. O’Keefe’s friends, who were legion, clogged the BPD switchboard with calls, demanding to know how the police could do such a thing. “It was like arresting Santa Claus,” the Boston Record-American noted. Within a month, the beloved tavern owner was found not guilty.

Santa Claus? The governor-puncher? Yes, for all O’Keefe’s ability to handle himself in the rough world he lived in, it’s his generosity that is best remembered today.

“He had a heart of gold,” says Corbett. “In times of trouble, he’d give you 10 or 20 bucks or whatever you needed, no questions asked.” The old man never turned down a panhandler or other unfortunate who wandered in looking for meal money or even a free drink. “Poor bastards,” O’Keefe told one reporter. “They could be any one of us.” He also helped out BU’s Buildings & Grounds workers when they went on strike in 1978.

And he was a father figure to thousands of BU students. (Remember, the legal drinking age was 18 in Massachusetts for most of the 1970s.) When O’Keefe died in 1987, Senator John F. Kerry (D-Mass.) marked the occasion during official proceedings of the US Senate, telling his colleagues, “The Dugout Cafe served as…a counseling center for students from Boston University.” Kerry (Hon.’05) (today the US Secretary of State) added that O’Keefe was the “definition of compassion.”

Crossroads of Terrier Nation

The Dugout remained popular with sporting old-timers—former middleweight world champion Johnny Wilson played cards there every night until closing time; Ted Williams stopped by to reminisce in 1981—but by the 1970s, the bar was most strongly associated with a college sport: BU hockey. The Terriers electrified the city that decade, winning three national championships and five conference titles. They earned seven Beanpot trophies and went to the Frozen Four almost every year.

“Believe it or not, these were the prescholarship days,” says Brian Durocher (SED’78), and players needed part-time jobs to get by. “It was a hockey tradition that your junior or senior year, you’d get hired at the Dugout,” whether as bartender, bar-back, or bouncer. (Durocher, who is now head coach of the BU women’s hockey team, was goalie and cocaptain of the national champion 1978 squad.) The whole team gathered in the old alehouse after games, along with the usual mix of fans, sportswriters, and assorted hangers-on. The jukebox featured “O Canada” for those players who hailed from north of the border.

Famously, the Dugout was open during the Blizzard of ’78, when at least two and a half feet of snow fell across New England. Hundreds of fans spent the night in the Boston Garden after watching BU beat BC in the first round of the Beanpot. Governor Michael Dukakis declared a state of emergency as snowdrifts covered entire cars and roads were impassable.

“Somehow,” defenseman Jack O’Callahan (CAS’79), a member of the 1980 “Miracle on Ice” US Olympic team that took gold, later told the Globe, “our team bus got back up Commonwealth Ave. to the campus. Suddenly, Coach Jack Parker [SMG’68, Hon.’97] halted the bus and said, ‘Gang, we’ve stopped here beside Marsh Chapel so we can offer a prayer of thanks.’ We all jumped out and went to Jimmy O’Keefe’s house of worship across the street—the Dugout Cafe.”

The next day, police enforced a ban on all but essential vehicles. O’Keefe reportedly got around this by having his beer delivered via a Boston Edison utility truck. The power was still out that night, and Durocher was serving beers by candlelight. Globe reporter Joe Concannon joked, “Can’t you do something about this?” Durocher just shrugged. At that, Concannon would write in the paper, “The lights and the jukebox went on. When your team is 20-0, you have it all under control.”

Durocher channeling the Fonz. A tongue-in-cheek tale told to illustrate a point?

“No, that was a real-deal, 100-percent true story,” says Durocher now. “It was the weirdest thing.” He shrugs and raises his palms in the air. “I just went like this, and the lights went on.”

Players still gather at the Dugout after the Beanpot. While literal candles are no longer needed, Corbett says the bar’s present owner “has done a terrific job as the keeper of the flame.” (Bill Crowley, Jr., inherited the place from his father, who inherited it from his longtime boss O’Keefe.) “It’s part of the fabric of the BU hockey family,” says Corbett. “The Dugout is the crossroads of Terrier Nation, and long may it run.”

Summing up the appeal of the little bar in a burrow, Corbett laughs while paraphrasing Ernest Hemingway: “All you need is a clean, well-lighted place.”

Patrick L. Kennedy (COM’04) can be reached at plk@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.