The Dresser: Imagining Huntington’s Seagull

Veteran designer brings elegant nuance to Chekhov classic

Cast members of the Huntington Theatre Company’s current production of The Seagull, at the Boston University Theatre. Photos by T. Charles Erickson. Drawings by Robert Morgan

At last month’s meet-and-greet kicking off rehearsals for the Huntington Theatre Company’s current production of The Seagull, the room erupted in applause after veteran costume designer Robert Morgan handed the actors his elegantly drawn visions of what they’d wear on stage. Morgan, who has designed costumes for such Broadway productions as The Full Monty and Dr. Seuss’s The Grinch Who Stole Christmas, has twice been nominated for a Drama Critics’ Circle Award. Former director of the College of Fine Arts School of Theatre, Morgan has been creating costumes for its productions on and off for nearly three decades. Now a freelancer who divides his time between the roar of the greasepaint and the stillness of Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, Morgan works in hectic bursts, sometimes applying his encyclopedic knowledge of period dress to design costumes, and depending on budget, sometimes to rent and forage for them.

For Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull—directed by Huntington favorite Maria Aitken (The Cocktail Hour, Betrayal, and Private Lives)—he is dressing actress Kate Burton, in the leading role of Irina Arkadina. Burton last appeared with the Huntington in 2009 in The Corn Is Green. Known for her prominent stage and television career, especially for her portrayal of bible-thumping Vice President Sally Langston in the ABC series Scandal and Ellis Grey in the ABC series Grey’s Anatomy, Burton has been nominated three times for a Tony Award, Broadway’s highest honor. In The Seagull, romantic intrigue, jealousies, and artistic temperaments ignite when Arkadina, accompanied by her novelist lover, visits her aspiring playwright son. Playing a famous actress, Burton is the most lavishly attired of the cast of The Seagull, which runs through April 6 at the BU Theatre.

Morgan spoke with BU Today about what goes into designing costumes for the theater, and how he weaves in the process his sprawling knowledge of history, class, textiles, lighting, and movement, as well as of the plays themselves.

BU Today: Will you design pretty much any production that comes your way, or does it need to be, so to speak, a good fit?

Morgan: Actually, some of the greatest experiences are jobs that I never would have thought someone would ask me to do. I did a wonderful production of Dr. Seuss’s How the Grinch Stole Christmas. It started in San Diego and then it went to New York and it’s been touring on and off for years. It’s a wild piece of design and I loved doing it. Now, somebody called me about five years ago expressing an interest in having me do a musical on SpongeBob Squarepants in Japan, and I thought, I’m not the right guy for this. But that was the only time.

Once you’re on board as costume designer, how much creative freedom do you have?

It depends on the director and how clear the production is in the director’s head. I do remember a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream I did once and the director said, ‘I’d like it to be late 19th century,’ and I presented him with a bunch of sketches that were late 1700s, and convinced him to move the period back 100 years. And in the case of The Seagull, Maria Aitken’s first instinct was to stay right on period in this production, which would be late 1800s. And I suggested about 1906, which got us out of the fussiest part of the Victorian era. I had a hard time imagining Kate Burton playing Arkadina in big mutton-sleeve dresses.

In the leading role of Arkadina, Kate Burton wears a linen costume designed by Robert Morgan.

Do poufy costumes sometimes inhibit actors?

It depends on the actor. Some actors love everything their costume does to them, and they use the restrictions of the costume cleverly and instinctively. Other actors rebel against discomfort. But in many cases, what may seem like an obstacle with clothing can yield very specific behavior. It’s very difficult to imagine an actress playing Arkadina, for example, who refuses to wear a corset. She wouldn’t walk properly, she wouldn’t hold herself properly. She would breathe differently. Her spine would collapse. We go to extraordinary lengths as technicians to make the period garments as actor-friendly and as comfortable as we can. In many periods women couldn’t raise their arms above their heads because of the way the sleeves were cut above the shoulders. But in a play, an actress may have to get her hand up above her head, so you figure out how to put elastics in certain places. There are craftsman-like solutions to most problems. For example, if an actress really has a hard time breathing in corsets, you can replace some of the canvas panels with elastic. And that is definitely true in opera, where breathing is the main issue.

So what looks to the audience like simply a dress really has much more going on?

Yes, there is a lot going on there. You start with the undergarments and the petticoats and the shoes and the height of the heel and the weight of the fabric, the cut of the garment. You know, some characters require rigidity and stiffness. Others need to feel like there is air under every petticoat and every skirt. We ask ourselves, how will the fabric move? How does it fall across the body? All of that is very important.

What periods in fashion history do you like most?

I love the 1790s. I love transitional periods. You know you’re moving from the typical 18th-century clothing, with all its silks and ruffles, into a revolutionary time in the 1800s. And over just a couple of years, clothes change radically and that transition is marvelously interesting and is the great thing about doing a play with characters of different ages who can fall anywhere in that span. Because old people would certainly wear old-fashioned clothing and the young kids would be in the cutting-edge stuff. And those transitional periods are not familiar to audiences visually. But every period has its own charm and its own problems in terms of cut, fabric, and how clothes get worn and why they get worn. The interesting thing about my job is that every time I do a play it’s different. There is endless variety.

What does a costume reveal about a character’s backstory?

I think that designers have to be like actors in that they have to understand what the story is. You don’t just choose clothing, you understand? One of the things I always do when I design a modern dress play is try to decide where everybody shops, how much money they have, what their taste is like, where they actually go shopping.

Take us through the process from design to creation.

Well, I always go back to research. I like it to a certain extent. I get very itchy to draw after I spend a lot of time researching. So what I like to do is go back to the research in the beginning, middle, and end of the process, because you can go back and look at what you’ve done and say, I think that collar should be cut differently, or maybe we can use this embellishment here. Just doing it at the beginning often doesn’t serve; you need to find answers to the specific problems that arise. Whenever you’re designing, you’re making selections. We change as we grow and we’re influenced by the culture that we’re a part of, so you’re always, by selection, reinterpreting a period. If you look at old theater costumes that are supposed to be different periods, you say, oh my word, I can’t believe they thought that was an accurate depiction of that period, because it’s so heavily influenced by the current period they worked in. With period dramas that were designed in the 1940s, you can see the ’40s all over those clothes. So no matter how truthful you think you’re being to a period, there is always an element of modernity to it.

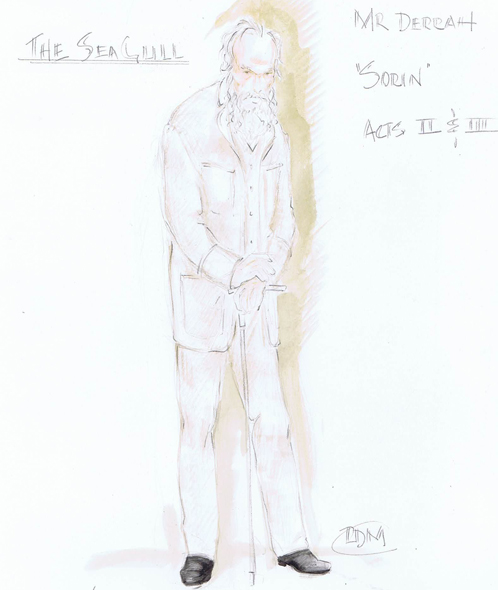

Thomas Derrah as Sorin and Morgan Ritchie as Treplev in The Seagull. Morgan’s drawing of Derrah’s costume is at right.

When you design a costume for a play like this, how important a consideration is the casting?

If you know the actor, you have a sense of what they project, what their essential elemental being is like. You have discussions with the director and the actor. You can either choose to heighten some quality that the actor already has, or in some cases you can attempt to provide something that the actor doesn’t project naturally. But that’s a very dangerous choice to make.

So you take into account an actor’s bearing?

Yes, or the actor’s sense of theatricality. Let’s say you have a very energetic person and you really think that languor is essential. Anytime you make a choice like that you have to be dead certain that the actor is completely on board and can use it. Because if the actor can’t use it, then you’re out there by yourself making a statement and the actor is going in a different direction, and you both look like idiots.

Tell us about color decisions.

Color is the fastest way to communicate something to an audience. There are color clichés, and color is the real basic building block of the design vocabulary. She wears a blue dress, red dress, black dress—instant associations. My problem as an audience member, which is where I want to be, is that when design is presented that forcefully to me, I get really uncomfortable and stop listening to the words. I say, “Oh, they’re telling me this.” And I don’t want to be told what I feel is obvious. I’m using color very specifically on the character of Nina in this play. She progresses through a series of blues, creams, and whites. I just couldn’t see her in any other color. The color is pretty much reserved for her, but I have to pick blues that are toned and so subtle, so the audience isn’t aware that she is being presented to you with that kind of innocence and truth, the connotations that blue has. It has to be handled really lightly and subtly. When it’s obvious, the story is over. Who wants to know at the beginning of a scene how it’s going to play?

What were some of the main considerations for you in designing The Seagull?

I’ve done this play before, but I must tell you that the first time you do a play of this complexity and depth, you’re really lucky if you can get a gloss on it, unless you have a director that can take you to the heart of it and is really a great communicator. Maria is extraordinary. She’s both a director and an actress, and she can think like both, and she’s a great communicator. After Maria looked at my sketches, I think every single one of Nina’s costumes changed, because Maria had a much more carefully thought-out and sensitive, in-tune knowledge of the character. I had made a lot of interpretive mistakes, and she was able to very clearly describe where I needed to take everything to correct it.

Can you give us an example?

In the second act, Nina turns up at the estate. She knows that she’s going to be there all day; she’s managed to get away from her parents. She’s completely overcome with the excitement of being in such a bohemian atmosphere with famous people. So she dresses very carefully for that event. I had done what I had thought was a beautiful sketch, but I had made her too fussy, too ruffly, too frilly, and too arch. She looked artificial. It looked as if she had quite an extensive wardrobe and she picked out her fanciest stuff and she was really done up. The mistake I made was that the costume did not project her basic innocence. It was too knowing, too contrived. Maria said, “I think this is lovely, but I think it needs to be a lot simpler. I think it just needs to be the simplest white dress you could possibly imagine.” So I went back and resketched it. I knew exactly what she meant, and I knew why. The dress is just simple and white and long, with a tiny bit of lace insertion and a bunch of tufts. It’s a nothing dress. Of course she’ll be beautiful in it, but there won’t be all the guile, artistry, all the fussiness of what I had originally designed.

What materials did you use for these costumes?

They’re all over the place. We have three acts that are in the summer, so there is cotton, silk, linen, light wool. That’s basically your choice.

Don Sparks as Shamarayev and Burton.

Can you use synthetic fabrics?

Sometimes. We’re using some synthetics on the petticoats because they hold up better and they don’t have static cling. The skirts ride better on them than the original petticoats, which would have been cotton and would have been starched. But we don’t want to put our wardrobe people through the agony of having to cold-water starch and press all the coats. That’s stupid. You need to make substitutions when you can. I sometimes like to use synthetic blends, because with certain costumes you can avoid wrinkles. Arkadina lounges on the ground in Act II, and I had originally rendered what I thought would be a linen skirt. But when I knew she was going to be on the ground at a picnic, I knew I couldn’t use linen, because she would look like wadded up newspaper by the end of the scene. Instead of using a synthetic, we bought very lightweight wool that won’t wrinkle, that will recover its smoothness.

With the shrinking of domestic marketplaces like New York’s Garment District, is it difficult finding materials for your designs?

You can’t find the beautiful old stuff you used to find. Like old ribbons—you could find old, woven ribbons that were very wide. It’s harder and harder to find fabric because no one sews at home anymore. I mean, could you imagine trying to design a Shakespeare play and only having Joanne’s to go to? That’s every costume designer’s nightmare.

How much do you have to know about lighting when you’re designing costumes?

If you work with the same lighting designer over and over again you get a sense of their color choices and you can talk to them and say, what are you thinking about for color in this scene. Now, the first act in this play is at night. There certainly will be a lot of clear light, blue light, and maybe some lavender light. Maybe there will be a little amber that comes from lanterns or something. So I know that the whites in that scene are going to jump, they’re going to be etched. So, dead white in that scene is going to be dangerous. Anytime you’re doing a night scene, that is the case. If you’re doing a daytime scene, the light designer can range from anyone who prefers the yellow side of the spectrum to a pink side of the spectrum. You don’t always know what’s going to happen. You hope for the best, and if something looks really wrong, you sit down and have a discussion. You say to the lighting designer, I’m having trouble with the color of the costumes; is there anything you can do to correct them, give it a little more purity?

What do you like about working with the Huntington?

I work with wonderful people in a really compatible atmosphere, with talented people out of the eye of the storm—which is New York. Working in New York is just hideous. It’s so hard. I’ve done enough shows there. I’m too old now. It’s so exhausting and the stress level is so high. There are so many people that want to be at that trough, that are fighting to get there, that they have no power over the process. I have been so lucky. Really, really lucky.

Hear more of Robert Morgan discussing his work on The Seagull here

The Huntington Theatre Company’s production of The Seagull runs at the BU Theatre, 264 Huntington Ave., Boston, through Sunday, April 6, 2014. Tickets may be purchased online, by phone at 617-266-0800, or in person at the BU Theatre box office. Patrons 35 and younger may purchase $25 tickets (ID required) for any production, and there is a $5 discount for seniors. Military personnel can purchase tickets for $15, and student tickets are also available for $15. Members of the BU community get $10 off (ID required). Call 617-266-0800 for more information. Follow the Huntington Theatre Company on Twitter at @huntington.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.