Anatomy of an Alcohol Transport

What actually happens when BU students drink too much

More than 460 BU students have been medically transported for drinking too much alcohol since January 2012. Photo courtesy of Flickr contributor Four12

Most students heading out on a weekend night to the GAP—Allston’s infamous house party district along Gardner, Ashford, and Pratt Streets—never imagine that their night will end in an emergency room. That, however, can be their final destination if they drink too much and pass out at a house party, stagger home along Commonwealth Avenue, or swipe a credit card instead of their student ID when entering their dorm—three actions that can suggest to friends, passersby, resident assistants, and security staff that they are in need of help from the Boston University Police Department.

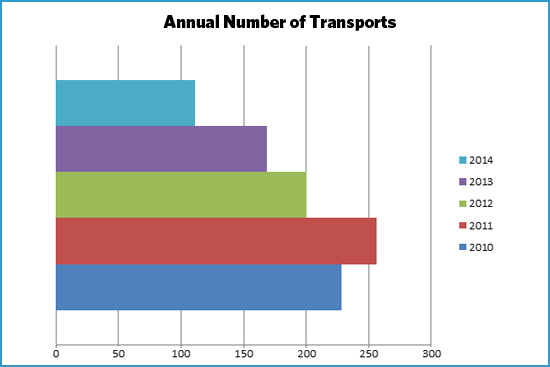

Since January 2012, the BUPD has overseen the medical transports of more than 460 students who drank too much, most of them freshmen and sophomores living in on-campus housing. Nearly an equal number of male and female students were transported across all age groups, except among sophomores, where roughly two-thirds of cases were women. A medical transport can be a frightening and embarrassing experience (parents are informed), so frightening and embarrassing that, police say, very few students require more than one. But unless a student has personally experienced it, what actually happens during a medical alcohol transport remains a mystery. To unravel that mystery, BU Today spoke with several people involved with transports. We also contacted students who had been transported, but none were willing to talk about the experience.

First, a little perspective.

“The reality,” says Leah Barison, a Wellness & Prevention Services counselor at Student Health Services (SHS), who works with students who’ve been transported, “is that one in three BU students chooses not to drink. And among those who do drink, two out of three do so responsibly. For the most part, people are not massively overdoing it, but they tend to think that others are doing it more.”

That skewed perspective can fuel rash decisions. “For a lot of students, their first year of college is the first time they’ve tried alcohol, and they aren’t aware of their limits,” says Katharine Mooney, director of Wellness & Prevention Services. “They just want to meet people and make friends, and alcohol is used as a social lubricant to do that.”

A call for help

Medical transports usually begin with a call to BU Police. Often, someone realizes that a friend or acquaintance is dangerously drunk. More often, an RA recognizes the signs of alcohol poisoning and calls for help.

“I’m certain that over the years, RA intervention in incidents involving intoxicated students has saved lives,” says David Zamojski, assistant dean of students and director of residence life.

When police arrive, they consider two options: they can bring the student in for protective custody to sober up, or they can call an ambulance to get the student medical attention. Most prefer the second choice. “We don’t know how much they drank or if they took drugs,” explains Thomas Robbins, BUPD police chief. “We want them to be safe.”

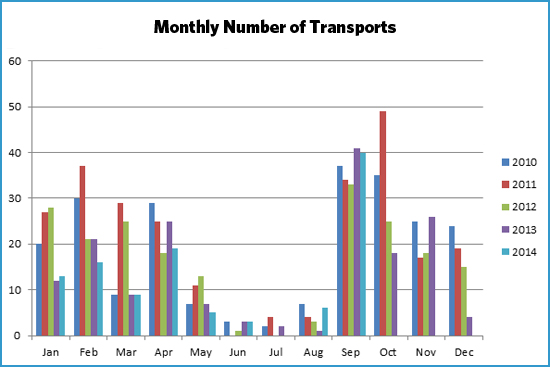

Since the beginning of fall semester, at least 40 students have been transported to the Boston Medical Center (BMC) emergency room. During the peak period, the weekend of September 25 through 28, 13 were brought to the hospital. That number alarmed University officials, who are now seeing the number of transports decrease as the semester progresses. September and October are historically the worst months for transports, and—for unknown reasons—February and April come in close behind. Overall, transports have been decreasing since 2011, when the number for the year rose above 250.

Students have criticized the BUPD, claiming that they send drinkers to the ER when they’re just tipsy, but Mooney says that’s not true, noting that last year’s average blood alcohol content (BAC) among transported students was 0.19, more than twice the legal limit in Massachusetts for driving.

Time as treatment

Andy Ulrich, executive vice chairman of the BMC emergency department, says impaired students arrive at his ER unable to have a coherent conversation, are generally uncoordinated, and often fall asleep. Sometimes he and his staff give students a Breathalyzer to get an accurate read on their BAC or start an IV to prevent dehydration. In most cases, “time is the treatment,” he says. “It’s a pretty standard equation, how long it’s going to take for their BAC to come down.

“Rarely do we have to do anything more extensive or more aggressive,” adds Ulrich, who’s also a School of Medicine associate professor of emergency medicine. “Certain drugs can be treated with an antidote or by pumping the stomach, but the effects of alcohol are so quick after you take it, there’s nothing left in the stomach to pump to lower the alcohol level.”

Ulrich says he worries less about alcohol poisoning than sexual assault and secondary injuries from falls or car accidents. He and his staff also monitor students for signs of drug use, and they try to determine whether the alcohol binge was spurred by out-of-hand social drinking or if it might mask a chronic problem, suicide attempt, or mental illness.

Students are free to leave the ER once they sober up, Ulrich says, and they are released into the custody of a family member or friend. The physical trauma is mostly behind them; now they face the mental, emotional, and social challenges awaiting them back on campus.

Alcohol 101

The University requires all medically transported students to attend counseling through Wellness & Prevention and to use an online educational program called Alcohol eCHECK UP TO GO, which provides accurate and personalized feedback. Barison and her colleague Dawn Belkin Martinez, an SHS social worker, receive a list of all medically transported students from the BUPD each week, and they reach out to them to schedule counseling sessions.

Barison says most come in willingly and express a mix of emotions. They feel disappointed in themselves, and they worry about what their families will think. They also worry about their scholarships and athletic status.

While her office encourages abstinence, Barison teaches harm reduction by attempting to provide students with the skills they need to drink safely. Counselors and students discuss drink sizes and alcohol content (a Solo cup filled to the brim is 18 ounces, or a beer and a half). They cover the meaning of BAC, and how weight and birth sex determine how much a drink will affect them over time. And they talk about alcohol’s biphasic effect, where one drink can act like a stimulant and feel good, but additional drinks push students to the “point of diminishing returns,” leading to a loss in coordination, speech, and judgment.

There’s a tendency to think that “some is good, more is better,” Barison says. “With alcohol, that’s not the case.” She helps students brainstorm strategies for how to drink more responsibly, such as eating beforehand, spacing out drinks, and sticking to a nightly limit.

Barison then sends students away with homework. They keep track of their drinking on a notecard and complete e-CHECK UP. She and the students review this information in a follow-up session, and they discuss a plan for moving forward.

Should the situation call for it, Barison may refer students to Behavioral Medicine at SHS for short-term mental health counseling or to an outside provider for long-term care. If she perceives a chronic drinking problem, she gives them a list of support groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous, which holds a meeting at Marsh Chapel every weekday from 1 to 2 p.m.

(No) crime and punishment

Students transported from residence halls meet with a Residence Life official to discuss the incident, while those transported from public property or off-campus housing meet with a Judicial Affairs officer. They are reminded that first offenses could mean University probation and a $100 fine. Second offenses up the ante. Students with a second on-campus offense could lose housing privileges, while those found off-campus or on public property could face deferred suspension. Third offenses are rare, but they could trigger suspension from BU.

“Things do change after a second transport,” says Alan Brust, Judicial Affairs assistant director. “If it happens again, you may have a serious problem, at which point we may have to talk about you going home to sort it out.”

Underage students often fear they or their intoxicated friends will get in legal trouble if they call the BUPD for help. Robbins says that unless they’ve committed a crime such as vandalism or assault, there will be no repercussions from his department. “It’s more important that you get help for your friend,” he says.

Zamojski says students who call the BUPD to have themselves or a friend transported do not face University sanctions. “The University will not give you a record if you get medical attention for a friend who needs it,” says Kenneth Elmore, dean of students. Bottom line, say all concerned, if you see someone in trouble from drinking too much, make the call. It could save a life.

Students have to remember “that they’re not bystanders,” Elmore (SED’87) says. “It’s up to all of us to look after each other” by acting confidently, managing a night out responsibly, and keeping an eye on those who don’t. “I want you to have all the fun you can stand,” he says, “but I want you to have a plan to do that.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.