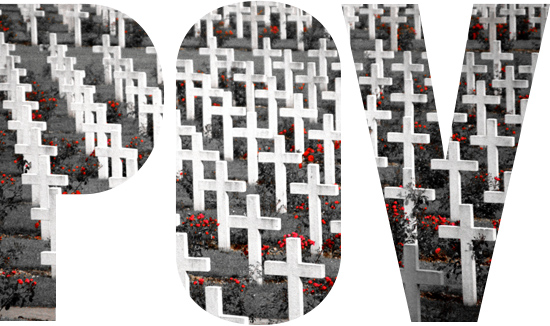

POV: The Legacy of World War I

A century later, its specter haunts us still

Nearly a century has passed since the guns of the Great War fell silent, since new grass re-covered scarred landscapes of the vast killing fields of Flanders and Verdun, Galicia and western Russia, since bright alpine flowers returned to the flinty battlefields of the Isonzo valley. A hundred years since terrible new flying machines lifted war into a third dimension and odd little U-boats took it down into a fourth. Yet a specter is haunting Europe still, and the world. A specter of total war. It stalks and hunts us all.

We have an uneasy (and quite inaccurate) shared memory that no one planned it, that it was somehow all a terrible and tragic mistake. It was not. The Great War was, as are all wars, the outcome of hard choice and callous calculation. It was also marked by blunder and miscalculation, incompetence and incomprehension, courage and folly, sacrifice and suffering, new marvels of efficient killing, and bloody murder on a scale the world had never seen before.

It was started by the two German-speaking powers, with contributory culpability and initial enthusiasm from Serbs and Russians, rather less from the French, little at all from the British. Others entered later, for venal reasons and most of the same illusions: Turks, Italians, Rumanians, Bulgarians, and Americans, until all the world’s great empires and most of its wealth and peoples were committed to years of total war.

We are horrified by its vast carnage, its waste of youth, matériel, and moral energy. We are tormented by suspicion that its 10 million dead settled very little or nothing at all, and made the decades that followed and the era we inherited far, far worse. We are right to thus remember it, for its immediate legacy was that it was completely indecisive on the major issues that really mattered. And that meant a second world war quickly followed, far more destructive and full of worse horrors, with more mass killing and learned hate.

Yes, the Great War ended four historic dynasties: Habsburg, Hohenzollern, Ottoman, and Romanov. Yes, it smashed apart two large multinational empires (Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman) and knocked large bits off two more (German and Russian). Yes, it spilled diverse and quarrelsome peoples into new and untidy states in the Balkans, Central and Eastern Europe, and across the Middle East, leaving us to live among the ruins and rubble of ghost empires even today. And although the two largest, the British and French, got bigger in its immediate aftermath, it mortally wounded them as well.

Yet, it left two key questions unanswered, so that a second and more terrible total war had to be fought inside a generation. First, unresolved was the problem of Germany’s ambition and place in the international system. Contrary to an enduring myth of the wanton harshness of Versailles, Germany in fact emerged from defeat mostly intact. Militarily and geostrategically, it was in a far superior position as it rearmed to again challenge the international order. The alliance that hemmed it in before 1914, and defeated it in 1918, fell apart: Great Britain (and America) quickly returned to old delusions of “splendid isolation,” abandoning France to face Germany alone. Paris also lost its traditional Russian ally, which withdrew into radical, armed isolationism under Lenin and Stalin, then allied with Nazi Germany in serial wars of aggression from 1939 to 1941.

More fundamentally, the Great War endorsed force as the main means of political resolution in Europe, even as it heralded a predicted culmination of military affairs in true total war: all-out commitment of all resources and populations of whole nations to total victory, by whatever means science and engineering and industry provided. Diplomats spoke of arbitration and conciliation and peaceful dispute resolution. It was mere veneer over the new reality, post-1918, that major states and peoples were less restrained in the use of force than before, far more willing, even eager, to employ any means against their enemies. In just 20 years Europeans graduated from slaughtering youths in uniform to mass starvation of “enemy civilians,” terror bombing of cities, and multiple genocides of unarmed peoples.

We like to think that Europe learned something from the war, that it concluded as it buried the last of 10 million dead sons in 1918 that “we must never do this again.” Yet, Ernst Jünger’s Storm of Steel, not Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front or the acute protest poetry of Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, is the real signature work of the 1914 to 1918 generation. Jünger’s celebration of hard vitalism and of war and nation, not pacifism or cosmopolitanism, is a sadly truer representation of postwar (interwar) views.

The Great War broke so much of the old order that hitherto impossible paths to power opened for thugs and criminals in a dozen countries, leading to thuggish politics internally, then internationally. Mass dislocations contributed to state takeovers by criminal gangs devoted to cults of social violence: fascisti in Italy, Bolsheviks in Russia, Nazis in Germany. And to their erection of savage, murderous, expansionist regimes. Its promise of revolutionary change through destruction displaced law among nations with ugly fascist and communist belief in the virtues of violence, in murder and war as positive moral instruments. This abiding fact of states’ easy willingness to use force as their ultima ratio was hidden by silkscreen rhetoric of diplomats and the League of Nations. Just as it is hidden today behind the façade of the United Nations. It abides nonetheless.

And so what came after the artificial thunder along the horizons stopped were brutalized societies in place of discarded older civilizations, and newly vicious ideologies that overtly celebrated state terror and mass murder as central means of social engineering. Fascism and communism were loosed into the world, along with other terrible men and ideas that scoured humanity into the mid-20th century, and beyond. The darkness was so deep it briefly eclipsed civilization, as all the major powers, even the more-or-less decent ones, descended into savage barbarity of means in a second world war that killed 65 million, mostly innocent civilians.

The central legacy of the Great War was a general barbarization of the world’s major societies that did not end for 30 years, if then. The vanity of powerful nations, the blood lust of leaders and ordinary folk, consummated a marriage to depravity in a worse total war fought without mercy or garlands. The ancient distinction between soldier and civilian was obliterated as states embraced obscenely rational methods of mass killing: starvation via naval blockade and air interdiction; Nazi Einsatzgruppen death battalions and death camps; the abattoirs of the Soviet Gulag and Holodomor in Ukraine; the Rape of Nanjing and lesser massacres across Asia; universal acceptance of terror bombing, including careful targeting of civilians (“morale bombing”) by air forces of the democratic nations: Britain, Canada, and the United States. For a dread moment in the mid-1940s, civilization stopped.

The Great War was a terrible rupture in the deep subduction zone of world affairs. It began a tsunami of mass killing that took 200 million lives by the end of the 20th century and caused mammoth disruption of the lives of billions of innocent people on every inhabited continent. Its floodwaters are receding, but they leave behind exposed ethnic, religious, and regional hatred from Ukraine to the Baltic, from Bosnia to Iraq-Syria, and many other places.

Above all, it undermined the modern idea that civilization is progressive. It is much harder today to believe that humanity is capable of making rational and moral advances, alongside more impressive but merely material and technical progress that promises near-certain future destruction. Its specter thus haunts us still, warning that we, too, may yet be surprised in our progressive and technological vanity by atavism embedded in our nature.

Cathal J. Nolan is a College of Arts & Sciences associate professor of history and executive director of BU’s International History Institute. His next book, The Allure of Battle: Delusions of Decisive Victory, 1700-1945, will be published by Oxford University Press in 2015. He can be reached at cnolan@bu.edu.

BU’s Center for the Study of Europe and International History Institute will host a special symposium and concert on December 11, 2014, titled Remembering the Great War: A Centenary Symposium & Concert. Find more details here. The symposium panels are free and open to the public. The concert, Music of War, performed by the vocal chamber music ensemble Gamut, is also free and open to the pubic, but because of limited seating, an RSVP in advance is requested to edamrien@bu.edu. Both the symposium and concert will be held at the Castle, 225 Bay State Rd.

“POV” is an opinion page that provides timely commentaries from students, faculty, and staff on a variety of issues: on-campus, local, state, national, or international. Anyone interested in submitting a piece, which should be about 700 words long, should contact Rich Barlow at barlowr@bu.edu. BU Today reserves the right to reject or edit submissions. The views expressed are solely those of the author and are not intended to represent the views of Boston University.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.