Tory’s Story

Archaeology buff, language lover, and BU’s only deaf freshman

Tory Sampson would have you believe she’s like any average freshman. She is passionate about her studies, has joined several clubs, attends campus events, and has already developed friendships she hopes will last a lifetime. She wants to spend a semester abroad studying in the Middle East and plans to become an archaeologist and explore ancient Egyptian ruins. She loves languages and is picking up her fourth, Arabic.

But anyone who meets Sampson (CAS’15) knows she is anything but average. She is singularly focused, eager to explore the new and test her own limits, and possesses self-confidence far beyond her 18 years.

She also happens to be deaf, and has been since birth. It is a fact that has never stopped her from accomplishing her goals.

“With interpreters, I’m on the same playing field as hearing students,” Sampson says. “There’s no reason to treat me any differently. I can do the same as any student.”

Sampson, who identifies herself as a member of the deaf community, grew up in San Diego, where she attended a mainstream public high school. Passionate about languages, she took French, played lacrosse, and blended in with a student body a third of whom took ASL as a second language.

“Coming to BU wasn’t a culture shock,” she says. Although it’s harder to find people who know ASL here, “it’s really a lot like high school.”

When it came time to think about college, Boston University was a natural choice, she says. Sampson, whose parents are also deaf and whose older brother, Matthew, is hard of hearing, had been to Massachusetts a couple of times on vacation with her family. She first fell in love with Boston then and was attracted to BU because of the reputation of its archaeology program. It’s a field she has been fascinated with since a fifth grade field trip, where she discovered a button during an archaeology dig.

Adjusting to life at BU, Sampson says, has been smooth. Like other freshmen, she found her classrooms, adapted to dorm life, and honed her time management and study skills. But she has had to juggle a layer of complexity most students never experience. She relies on a light instead of an alarm clock to wake up each morning, works with the Office of Disability Services to schedule ASL interpreters for classes or campus events, and must arrive 15 minutes early to snag a front seat. And she always carries a notepad so she can talk to anyone she meets who isn’t fluent in ASL.

“Many people think I have an interpreter with me 24/7,” she says, adding that children sometimes ask if she has ears. They seem relieved when she pulls back her wavy golden hair. “I’m just a normal person. I’m happy to change the way they’re thinking.”

On a Tuesday afternoon early this semester, Sampson sat among students at a horseshoe-shaped table in a Core Curriculum humanities class with Jennifer Knust, a School of Theology associate professor of religion, as they discussed Buddhists’ belief in the endless cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

Sampson scanned passages in The Life of the Buddha and absorbed the discussion with signing from BU ASL interpreter Christopher Robinson and freelance ASL interpreter Janine Sirignano, who sat to the left of Knust’s podium and took turns interpreting.

The rapid-fire theoretical discussion was hard for the uninitiated to follow, and visibly intense for the interpreters. They paused as Sampson took notes and continued when they had her full attention. When Sampson flashed a quick smile in response to Knust’s occasional jokes, it was 30 seconds after the punch line. She participated in the discussion via the interpreters and never shied away from clarifying her response if she sensed it hadn’t been fully conveyed the first time.

One of the courses Sampson took fall semester was Arabic, but she quickly discovered that it concentrated heavily on listening and speaking, while she needed to focus on reading and writing the language. She dropped the class after a month and worked with Hanan Khashaba, a CAS lecturer in Arabic, and the Office of Disability Services to create a directed study course for spring semester that met her goals.

Diving into uncharted territory

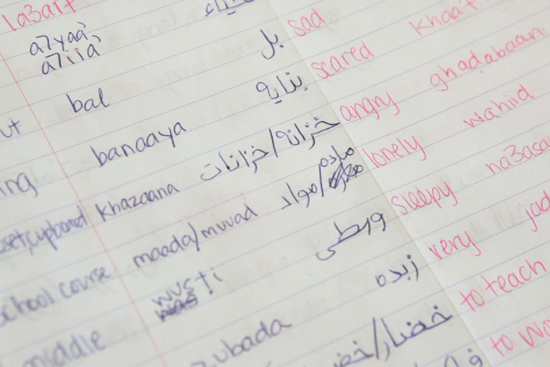

On a Friday morning in February, Sampson sat at a conference table with an Arabic workbook, her notebook, and a miniature whiteboard. Two interpreters, Caity Cross-Hansen and Linsay Murphy, sat to her right, rotating every half hour, while Khashaba stood a few feet away at a larger whiteboard. They were about to dive, as they do three times a week, into uncharted territory.

English speakers studying Arabic must learn a new alphabet, get accustomed to writing and reading right to left, and acclimate to sounds that have no direct translation in their native language. Imagine being an interpreter who must distinguish those new sounds and transliterate them into ASL. Then imagine the challenge for Sampson, who must stick those hybrid signs together and create words in a language she cannot hear.

Over the course of an hour Khashaba taught Sampson new letters, common pronouns, and how to conjugate “to have.” She then pulled out a shopping bag and mail from the Middle East to work on translations. Finally she told Sampson to write three sentences in Arabic describing herself.

Most first semester students, Khashaba says, make it through three units in her class; Sampson will undoubtedly finish six. “She always asks for more—more vocabulary, more homework,” Khashaba says. “I have to have backup plans with me all the time.”

“I’m taking Arabic because I don’t want to be one of those typical Americans who go into another country and say, ‘I expect you to know my language,’” Sampson says. “That’s not what I want. I want to go to a country and show that I have respect for the people of that country and their culture.”

And there’s another side to her interest. “I’ve found that if I meet someone who learns ASL and tries to communicate with me,” she says, “I have so much more respect for them. I’m glad that they actually try. I’d like to do the same for Arabic speakers.”

In addition to learning Arabic, Sampson has taken on another challenge: trying to master the tango. On a recent afternoon, she watched as BU ballroom dance instructor John Paul was urging students to “listen for the rhythm” of the tango music before pairing up to practice their new moves.

“Gentlemen, you should be very busy,” Paul said, a nod to the overwhelming ratio of women to men in the class.

Paul extended a hand to Sampson, who accepted as her cheeks flushed apple red. She did not hear the tango music playing from a nearby stereo. (Only loud noises—like planes, screams, or a passing motorcycle—register for her.) Her brow furrowed slightly as she concentrated on the complicated moves of the dance. Dancing requires trust between partners; dancing deaf ups the ante on that.

Back on the sidelines, Sampson practiced with her friend Rebecca Lopez (SED’15), who knows ASL. The two laughed, joked, and twirled each other around in a separate section of the dance floor.

Sampson says she can’t believe her first year of college is almost over. She’s already looking forward to the fall and pursuing more archaeology and anthropology classes (she recently decided on anthropology as a second major). But first things first: she needs to pack for China. She and her brother are spending a month this summer traveling through Beijing, Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Chongqing.

Apparently a love for languages is a family trait—Matthew is fluent in Mandarin.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.