Strange Bedfellows

Unique collaboration makes case for philosophy's relevance

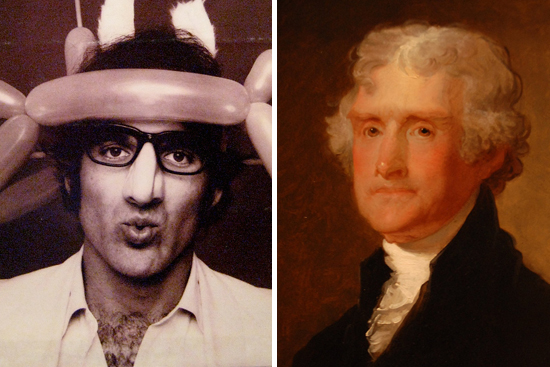

Famous philosophy majors Steve Martin and Thomas Jefferson. Martin photo courtesy of Tim Yates. Jefferson painting photo by Metal Chris.

A finance major and a philosophy professor are in a room. (No, this isn’t the setup for a joke.) The prof has just given the student a less-than-stellar grade on a paper, which makes this prelude to collaboration all the more bizarre. Yet that meeting led philosopher David Roochnik and Pooja Sahani (SMG’14) to launch a campaign extolling the virtues and relevance of philosophy for everyone—even business students.

It began earlier this semester when Sahani met with Roochnik, a College of Arts & Sciences professor and chair of philosophy, to talk about that paper. “I told him I’m a management student…but I took a risk” by taking philosophy classes, she says. His reply: “You’re doing the best thing you could do…just to become a more engaging person in life. And that’s the point of school.” When she mentioned her interest in a consulting career, Roochnik told her he needed a consultant for a problem that’s been bugging him: the number of philosophy majors has fallen from 194 five years ago to 138 currently.

He and Sahani struck a deal: the department would pay $1,000 to hire her and her fraternity, Alpha Kappa Psi, whose members share an interest in business, to study the slide and arrest it if possible. The fruit of that effort is a panel discussion tomorrow night featuring Roochnik and several philosophy major alums who’ve struck career gold in fields from technology consulting to webinar production. Posters advertising the event also plug famous philosophy majors, from Thomas Jefferson to Steve Martin.

The campaign comes after Sahani, who is minoring in philosophy, and her frat peers surveyed more than 130 students across BU’s schools about whether they’d taken a philosophy class and why they didn’t take more, or any.

“A majority of the students don’t see much value in a philosophy degree,” Sahani says she discovered. That indifference isn’t confined to BU; the University of Louisiana at Lafayette dropped its philosophy major two years ago, citing cratering student interest. On the other hand, the percentage of American college degrees in philosophy and religious studies (data collection lump the two together) rose slightly between 2000 and 2010, although it remained small, says Amy Ferrer, executive director of the American Philosophical Association at the University of Delaware.

Still, Roochnik sees rough seas ahead for the humanities—he’s heard similar concerns about a dearth of majors from colleagues in BU’s history department—as the Great Recession and parents’ concerns for their children’s income prospects put a premium on career-oriented majors. “BU has a very fine tradition of supporting liberal education and therefore the humanities,” he says. “That’s why I came to BU 17 years ago.…But clearly, the emphasis at BU is shifting to the technical fields.” Even once the recession ends, cost pressures in higher education will continue to make popular, career-focused disciplines more attractive, he says.

Yet students deceive themselves by thinking philosophy is useless, Sahani argues. A business student with liberal arts subjects like philosophy under her belt stands out from competitors for that corporate job who’ve never broadened their studies, she says. “I had an informational interview with the vice president of Goldman Sachs two years ago. He’s an English major.”

Philosophy also has provided a mental treadmill, adding muscle to her business skills. “Philosophy teaches you how to be logical, and to be an exceptional businessman or businesswoman you have to be very logical to solve problems, whether they’re ethical issues or how to increase a company’s profit. And sometimes, the management classes we’re taking now don’t train your brain to think that way. Companies trust that liberal arts brain to be knowledgeable, to be analytical.”

Alec Dalton (SMG’15, SHA’15), another student helping with the project, says business law and ethics are rooted in philosophy. “Ethics is such an enormous part of what we’re studying in business today,” he says, “especially when you consider things like the 2008 financial downturn,” abetted as it was by Wall Street venality.

Jennifer Bower (CAS’13) took just one philosophy class, on argumentation and reasoning, and that was back in freshman year. A few weeks ago, she took the Law School Admission Test. “My almost natural ability to read, comprehend, and analyze the majority of the questions on each practice test was from what I had learned in the philosophy class I took almost three years before,” she says.

The student philoso-philes have been promoting philosophy’s relevance in day-to-day conversation with peers, and Sahani has convinced at least one who had never considered taking a philosophy class to give some thought to one in the future. “I viewed philosophy as a very abstract…study that did not have much practical purpose,” says Aaren Johnson (CAS’16), who is weighing a degree in political science. After talking with Sahani, he says he’s now interested in taking a course in the philosophy of politics.

Some of the surveyed students who’d taken philosophy classes reported that they’d found the subject inordinately difficult, with its analytical emphasis and heavy amount of writing. But Sahani points out that some classes require no prerequisites (for example, Philosophy of Film and Philosophy of Sport).

And for students seeking a challenge, those tough classes can be rewarding, as she knows from experience: “I’m taking Philosophy 300. It is a very hard class. But I’ve never felt so fulfilled. Ever.”

The panel discussion tomorrow, Thursday, November 1, is at 7 p.m. in the Metcalf Center for Science and Engineering, Room 109, 590-596 Commonwealth Ave.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.