In the Beginning, Man Created…

BU poised to become a synthetic biology powerhouse

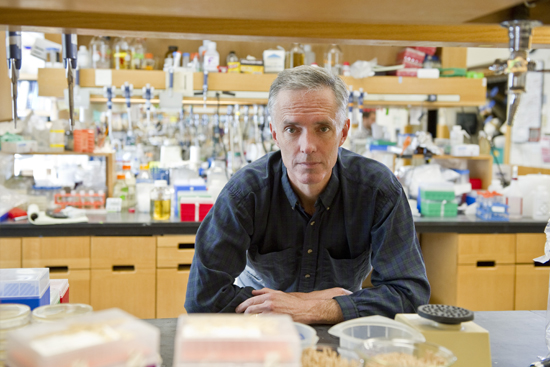

ENG’s James Collins says synthetic biology is “genetic engineering on steroids.” Photos by Kalman Zabarsky

The age of synthetic biology was turned on, literally, with a switch built by two BU researchers 13 years ago. James Collins, now a William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor and a College of Engineering professor of biomedical engineering, and his graduate student Timothy Gardner (ENG’00) altered the genes of E. coli bacteria so that they could be made to produce proteins or not produce proteins, essentially creating a two-gene on/off switch for a biological circuit.

The researchers described the achievement in a paper published in Nature in January 2000, an issue that also described a three-gene oscillating circuit built with the same genetic components by two Princeton physicists. Exactly 10 years later, Nature described the work done at BU and Princeton as the “defining pair of experiments” that mark the start of synthetic biology.

In those days, says Collins, who is also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, the Human Genome Project had captured the attention of cutting-edge biologists, as well as of the press. It would be years before the appellation “synthetic biology” entered the vernacular, and more important, before the science was distinguished from genetic engineering. Today, he says, the difference between the two fields is almost as clear as on and off.

“What genetic engineers were doing was cutting and pasting,” says Collins. “They were introducing genes to enable organisms to be production organisms—they were essentially swapping a red lightbulb for a green lightbulb.” By contrast, he says, synthetic biologists design and build the circuits that power the bulb. “Introducing the lightbulb is not engineering. That’s home design. Designing the circuit is engineering. Synthetic biology is genetic engineering on steroids.”

Collins’ standard definition of the field goes like this: “Synthetic engineering is a new field that is bringing together engineers and biologists who design and construct biomolecular components and synthetic gene networks to reprogram cells, endowing them with novel functions.”

The novel functions he refers to include the production of new fuels and medical treatments. Collins was recently awarded a Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation grant to engineer a yogurt bacterium that will respond to, and kill, cholera bacteria in the human intestine.

Synthetic biology has intrigued scientists at dozens of research institutions, but the field’s alpha schools are generally considered to be the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of California, San Francisco, on the West Coast, and Harvard and MIT on the East. Recently, however, with encouragement from President Robert A. Brown, as well as Jean Morrison, University provost and chief academic officer, and Kenneth Lutchen, ENG dean, Collins has been strengthening the ranks of synthetic biology expertise at BU.

Douglas Densmore, the Richard and Minda Reidy Family Career Development Assistant Professor in the ENG electrical and computer engineering department, came to BU two years ago from UC Berkeley. Ahmad “Mo” Khalil, an ENG assistant professor of biomedical engineering and a former postdoctoral fellow under Collins, joined BU last fall. Also last fall, Collins helped to recruit Wilson W. Wong, an ENG assistant professor of biomedical engineering and previously a postdoctoral scholar in cellular and molecular pharmacology at UC San Francisco. The recruits, who like Collins work in a large, new state-of-the-art lab at 36 Cummington Mall, belong to a happily incestuous community: Khalil earned a PhD at MIT, which is a member of SynBERC, the Synthetic Biology Engineering Research Center, where Densmore was a postdoc. Collins is also affiliated with Harvard through that university’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering.

“You could build it around the four of us,” Collins says. “And I don’t think there’s much doubt that BU is a major player in this exciting new field.”

Read Part I: Software Apps Help Synthetic Biologists Work Faster and Better.

This article was originally published in the fall 2012 issue of Bostonia.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.