Handling History Instead of Reading It

Class gives presentation at Mass Historical Society tonight

Tonight students will give a public talk and presentation of artifacts titled Making History: King Philip’s War in Documents and Artifacts at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston. Photos by Chitose Suzuki

A conflict featuring torture, the starving and enslavement of POWs, and racial and religious prejudice, with attempts to convert those on the other side. Today’s war on terror, or civil strife in some modern despotism?

Nope. Here’s another clue: this conflict killed a greater percentage of the American population than any other war in our history. If you’re thinking the Civil War, wrong again. These facts belong to King Philip’s War (1675–1678), a colonial catastrophe involving New England’s settlers and their Native American allies against tribes led by Metacom, sachem of the Wampanoag, known as King Philip to colonists. The war not only wiped out entire settlements and took 4,000 (mostly Native American) lives, but also ended the era of armed resistance to colonization.

For most college students, studying this 334-year-old pivot point in American history would involve listening to lectures. James Johnson’s students are giving one.

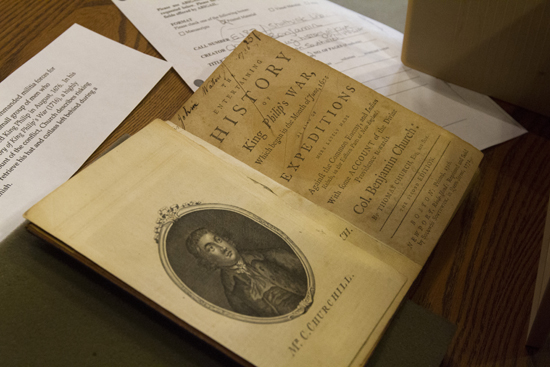

Tonight, at the Massachusetts Historical Society, the 20-plus students, most of them freshmen wrapping up their first semester of college, will give a public talk and a presentation of artifacts from the war: the flintlock from the gun that killed Metacom, a food bowl he used, a cutlass carried by a colonial commander the day Metacom died, and contemporaneous written accounts about the conflict, among them a Puritan minister’s diary containing his sermon topics and his conversations with Indians about converting to Christianity.

Making History: Conflict and Community in Boston’s Past is one of several courses involving innovative teaching techniques that the University Provost’s Office has jump-started, according to Johnson, a College of Arts & Sciences associate professor of history. His course syllabus says that it’s “designed to involve students in the very activities practicing historians carry out.” Besides mounting an exhibition at the Historical Society, Johnson’s students have learned about Boston’s 1970s busing crisis by touring Roxbury and the South End with former mayor Raymond Flynn and former state senate president William Bulger (Hon.’96). They’ve taken an architectural tour of Copley Square to study how European tastes and immigrants remade the city during the Gilded Age.

Yes, Johnson does lecture. But so did a Historical Society staffer, on how to do archival research. And on a brisk, sunny December day, professor and students hoofed it to the society’s ornate building on Boylston Street to rehearse tonight’s presentation, donning white gloves and gathering around artifacts-laden tables as society representatives gave tips on arranging and discussing the treasures.

Some of the suggestions were mundane (don’t dress like a slob; make sure any books displayed are open to an interesting page, like a description of Metacom’s death). But at the table showcasing that death, society art curator Anne Bentley wielded an 11-pound long gun and showed the students how the flintlock would have fit on it.

“It goes through the wooden stock and it goes through the barrel,” she explained. “This locking mechanism would release, and the metal on the metal would create a spark that would ignite the powder.”

“I’m a history major, and this is the best class I’ve taken so far,” said Philip Tankovich (CAS’15). “With the presentation, you put so much more effort into it,” not just reading about the war, but speaking about it to those who’ll attend the exhibition. “You have to talk to people,” he said. “There has to be not just analysis, but expression of that analysis as well, so that people can understand it. It’s definitely a multidimensional project. It’s cool.”

Mercedes Bonilla (CAS’15) plans to major in Latin American studies, and Johnson’s class has made her want to travel to that region for similar hands-on work. “It’s not just reading an article about the war; I’m actually looking at the texts that they wrote…or the weapons that killed people, or the bowl that might’ve held their food.…It’s no longer that illusion. It becomes very real.”

The course has been a learning experience for Johnson as well: he’s a European cultural historian and has never taught about Boston before. “I was intrigued about the idea of doing something totally different from the kinds of courses we normally teach,” he said.

As for his students, he hopes they get “a deeper understanding of what goes into interpreting the past and how a certain amount of that is really piece by piece by piece, matching together fragments and bits of partial stories.” On the first day of class, he asked the students why we should study the past. Most said so as not to repeat its mistakes. Johnson will repeat the question on the last day of class, “and I hope that they have a much more subtle understanding of why we study the past.…What we today look back and call mistakes were part of a complicated network that makes it not so easy to say, ‘Let’s avoid those mistakes now.’”

After all, he says, the class has discussed how the trappings of King Philip’s War—fears of another culture, talk of whose side God is on, allegations of torture—are familiar to anyone in our post-9/11 world.

Making History: King Philip’s War in Documents and Artifacts is tonight, Thursday, December 13, with a reception at 5:30 p.m. and the presentation at 6, at the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1154 Boylston St., Boston. The event is free and open to the public.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.