Defying Gravity

BU satellite team goes weightless

Seven College of Engineering students are still walking on air, at least figuratively, after a recent opportunity to test their satellite design at near-zero gravity. Members of the Boston University Student Satellite for Applications and Training (BUSAT) team participated in a weeklong series of microgravity flights over the Gulf of Mexico in late August.

“It was one of the coolest things I’ve ever done,” says mechanical engineering graduate student and project manager Nathan Darling (ENG’13). Through NASA’s Flight Opportunities Program, the students were able to test and fine-tune the space-worthiness of a prototype modular satellite designed to deliver scientific instrumentation into orbit. They also learned to work upside down in rapidly changing gravity environments and perform on-the-fly equipment repairs to ensure a successful test.

Not only did the flights provide valuable insight into their satellite’s performance in a space-like environment, but “it’s pure gold,” Darling says, for student spaceflight engineers to be able to count this among their experiences. “We’re all really interested in aerospace careers.” Just being at the Johnson Space Center was a thrill for the young engineers, who returned to Boston sporting NASA T-shirts. Team members got the idea to apply for the program at the annual AIAA/USU Small Satellite Conference, held in Logan, Utah, in August 2011, recalls Christopher Hoffman (ENG’13). “We met a team from Colorado, and they had a video of themselves testing their satellite in a microgravity environment.” The BU team worked through the application process, and a proposal written by microgravity team members Darling and David Harris (ENG’15), who is also president of the BU Rocket Team, was approved last winter.

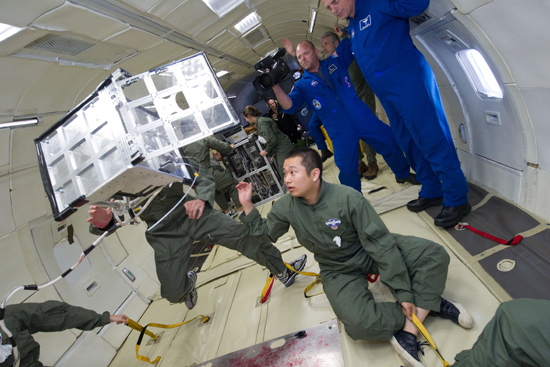

During the team’s August flights, which took place in a modified Boeing 727 jetliner, the students floated for periods of 25 seconds at a time, first with limbs akimbo and eventually with a measure of control, while testing the satellite’s hardware. Of specific interest was the dynamics of a door-like component on their satellite holding a solar panel. They’re hoping that the satellite, which resembles a contemporary end table, will facilitate many future space research missions—technology that “will make scientific instruments that fly in space as easy to use as your USB mouse,” Darling predicts.

Funded in part by the U.S. Air Force through the University Nanosat Program, the satellite project is the result of six years of efforts by more than 60 undergraduate and graduate students studying engineering, computer science, physics, and astronomy. Ted Fritz, a College of Arts & Sciences astronomy professor, provides project leadership through the BU Center for Space Physics. Fritz has appointments in the ENG mechanical engineering and electrical and computer engineering departments as well. The student project is also supported by contributions from ENG and CAS.

“The team did very well,” says Fritz, who along with the BUSAT students has fingers crossed for the final satellite competition review, on January 10 at Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, N.M. “They’d searched out the microgravity possibilities and all I had to do was bless it,” Fritz says. “That they went through all this and are still speaking to one another is quite impressive.” He says all of the current BUSAT team members hope to commandeer some type of van to drive out to Albuquerque together.

NASA’s Flight Opportunities Program provides low-cost access to suborbital space, about 60 miles above sea level, where researchers can expose their technologies to brief periods of weightlessness in a reduced-gravity environment using both commercial aircraft and rockets. The program also offers them the opportunity to loiter high in the Earth’s atmosphere using commercial balloons. The BUSAT team’s flights—three in all—lasted about two and a half hours each, with up to 60 fleeting periods of microgravity simulated by the plane going into a controlled free fall.

If that sounds sickening, it often is. Rarely a flight goes by without at least one, and usually more, scientists experiencing motion sickness, in spite of the standard preflight shot of antiemetic. But unlike many fliers, “none of the BU students threw up,” says Steven Yee (ENG’11,’13). A two-hour safety session helped prepare them to take precautions (never lose your grip on any object, large or small), but it could not have properly prepared them, he says, for “the sensation of sitting and suddenly there’s no force on your butt.” The inside of the plane’s stripped-down fuselage is completely padded so no one goes careening into hard metal. But the effort involved in focusing everything from limbs to eyeballs can be draining. “We were exhausted by the experience,” recalls Yee, who along with other teammates gained physical confidence with each spin, and ultimately gave himself over to that weightless feeling.

The experience was unlike what many of the students had expected. (Yee was thinking, wrongly as it turned out, “roller coaster.”) Once familiarized with the sensation, and the fleeting time available to test the solar panel door, the students “ended up doing a lot of work upside down,” says Erik Knechtel (ENG’14). Working the solar panel mechanism as it hovered in front of them, the team discovered that the spring action, which worked fine in the lab, needed some modification to function easily at zero gravity. With the device suspended in air, team members even “did some wire stripping with our teeth,” to repair a faulty circuit, Knechtel recalls.

A level of vigilance was required to make sure no parts drifted away, according to Darling. In near-zero gravity even the tiniest wayward screw or washer could lodge in the aircraft’s control systems and endanger the entire aircraft, so if a part can’t be accounted for, the craft is grounded until the part is found. “At one point we accidentally set a few washers loose, but Josh grabbed one and Chris grabbed another,” says Darling.

The BU team happened to be in Houston when Apollo astronaut Neil Armstrong died at age 82. Four BUSAT team members were on board the final flight of the week, when the pilot performed a memorial lunar gravity parabola in honor of the Apollo 11 astronaut. Armstrong, an icon of early American manned spaceflight, used similar parabolic microgravity testing for equipment used to develop lunar lander missions.

If the BUSAT team is selected as competition winner in January, members will have two more years to bring their satellite to flight status, with funding of $55,000 each year, says Fritz. In the meantime, he says, “to give you an idea of how enthusiastic this crew is, a call for proposals for a competition to design CubeSat, or miniature variety satellites, was just announced—and Tuesday we submitted two proposals.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.