Did Hip-Hop Help Obama?

BU alum tracks the hip-hop industry, from 1968 to 2008

More than 30 years ago, hip-hop subculture thrived mainly in NewYork City’s Harlem and the Bronx. Even as hip-hop grew in popularityamong young people, those who held the power to popularize thegenre—record companies, radio stations, and MTV—wanted nothing to dowith it, fearing it was “too black.”

In The Big Payback: The History of the Business of Hip-Hop (New American Library/Penguin, 2010), Dan Charnas (CAS’85, COM’85) examines hip-hop’s evolution, particularly the business deals that madethe industry what it is today. To understand how hip-hop became soculturally ingrained, Charnas writes, it’s necessary to understand thetalent and recording industry executives who negotiated contracts andhunted for the next big star. A hefty 672 pages, the book often readslike a novel, bringing the characters—such as emerging moguls RussellSimmons and Rick Rubin—to life.

In hip-hop’s early days,kids looking to make a quick buck would spin records at local parties,rhyming along with the music. As they progressed and learned how to useturntables, the crowds and competition grew. In the 1990s and 2000ship-hop surged, as well-known rappers like Tupac Shakur, the NotoriousB.I.G., and Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs gained huge followings. Charnascredits hip-hop with helping the United States resolve long-standingracial issues, bring the country together, and educate a generation.

Charnas has written for The Source magazine and the Washington Post andworked for Profile Records and Def American Recordings. He earned amaster’s at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, wherehe was awarded the school’s top honor, a Pulitzer Traveling Fellowship.He is also a Kundalini yoga instructor. BU Today spoke with him about his book and about what hip-hop means to America.

BU Today: The idea for the book came from a magazine article you proposed, yetnever published, about the first generation of white and ethnicentrepreneurs whose disco-and-dance record labels were saved by hip-hopmusic. How did the book evolve?

Charnas: Actually,this book has its genesis, at least its spiritual genesis, at BostonUniversity. I graduated in 1985. I was a communications and liberalarts major and an editor of the Muse, part of the Daily Free Press.

Hip-hop was surging in cultural importance while I was in Boston. Iminored in African American studies—my senior thesis was on racialsegregation in the music industry. It analyzed white America’srelationship with black culture over several hundred years. At the endof the thesis I forwarded the notion that hip-hop could actually helpresolve the ambivalence that white America felt towards black folks andblack culture. Hip-hop was vitally important in educating and preppinga generation for a new multicultural society.

The booktracks from 1968 to 2008 and ends at Barack Obama’s election. I thinkin many ways hip-hop has been a part of setting up the conditions forthat to have occurred. I think, ultimately, that’s the importance ofhip-hop in the late 20th and early 21st century. I wanted to write abook that would really place hip-hop in American history.

Can you explain the title?

Can you explain the title?

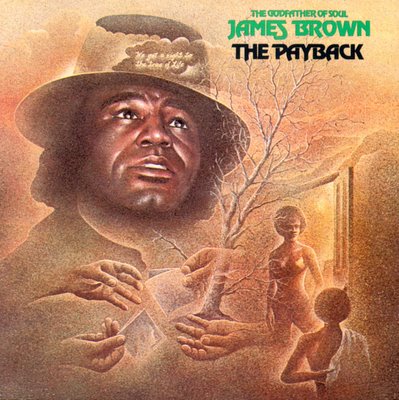

“The Payback” is an old song by James Brown. It’s a song about revenge—someone took his girl, so he’s going to mess this guy up. When you say“the big payback,” it’s very well known to people in hip-hop culture.But it’s also a triple entendre. It’s called “the big payback” becausethere are a lot of people who invested their lives, their fortunes,their reputations, and everything in the notion that hip-hop could beas powerful as any American music culture that preceded it.

But in another way it’s payback meaning revenge on America, meaningmainstream American culture took so much from black culture and blackpeople.

What was the most difficult part of writing the book? Were there stories that people didn’t want told?

I would say the prospect of getting access to everyone was very scary.I didn’t get everyone, but I got the most important people. The fewfolks I didn’t get I could report around, meaning I could get theirstory without actually talking to them. I would say the hardest partwas working a full-time job in media and writing this book at nightwith a new wife and a new baby. I’m still tired.

A big complaint about hip-hop is the amount of violence and misogyny in the lyrics. Do you believe that’s true? Is it changing?

One of the things I say in the intro to the book is that a lot ofpeople feel that hip-hop is not worthy because it’s materialistic,vulgar, and misogynist. I think those conclusions are unfair. Those arenot hip-hop’s ills—those are America’s ills, and hip-hop is a child ofAmerica. And as hip-hop became more mainstream, it adopted those valuesof materialism, of celebrity worship. I’m not saying that that stuffdidn’t exist in the music before it became successful, but that thosewere real experiences that came from the milieu in which this musichappened.

I think that as subcultures become mainstream, they do become debased.I think that one of the things that we lost in hip-hop is that it usedto be very diverse. You could have political hip-hop and comic hip-hopand female rappers along with male rappers, and there was this verymuch back-and-forth, give-and-take on the hip-hop scene. But we lost alot of that. Because things have become so successful, for many peopleit’s more of a path to cashing in than it is something you do for thelove of it.

Do you think there will be any more hip-hop moguls like Russell Simmons or Jay-Z, or are they a dying breed?

Hip-hop tended to breed people who thought like businesspeople, becausethey were on the outside. Russell Simmons had to do what he did andJay-Z had to do what he did because there was no one doing the work ontheir behalf.

I’m going to put Damon Dash in there with Jay-Z, because as a team,when they were rejected at labels, they made their own—existinginstitutions didn’t work out for them. Russell Simmons made his owninstitution, his own industry.

Now that there areinstitutions, I think there are people who don’t feel the need to beentrepreneurial. But then again, the music industry is falling apart,so everyone needs to be entrepreneurial. Who is next I’m really notsure. All of our current moguls were made during a time when the musicindustry was a lot more powerful than it is now. I don’t know whathip-hop culture is going to produce next; all I know is that it won’tlook like the hip-hop of previous years. It will surprise us all.

You’vedescribed the book as the story of “a generation of African Americanscarving out their own economic space in corporate America.” What wasthe typical route to hip-hop success?

Hip-hop started asthe kids in the Bronx who couldn’t afford to dress up, who weren’t oldenough to get into Harlem nightclubs, so they made their own partiesinstead. They created their own cottage industry. And then there wereechoes. Institutions turned hip-hop away because they didn’t think itwould make money. Even if they did think there was money to be made,the racial, inner-city part of it scared them.

Take Russell Simmons. No one wanted to mess with his art, so he tookartists into his small fringe music label, and that grew. Rap music wasturned down by MTV, so smaller video shows sprang up to fill the void,and the same thing happened with radio stations too. For many yearsthere were no pop radio stations playing rap music, so KDAY in LosAngeles filled the void.

Take Russell Simmons. No one wanted to mess with his art, so he tookartists into his small fringe music label, and that grew. Rap music wasturned down by MTV, so smaller video shows sprang up to fill the void,and the same thing happened with radio stations too. For many yearsthere were no pop radio stations playing rap music, so KDAY in LosAngeles filled the void.

The phenomenon of being shut outpushes you to do your own thing. Take the rappers that have startedtheir own clothing companies, like Roc-A-Fella founders Damon Dash andJay-Z. Rocawear, started by the two, has a chance to be an enduringAmerican brand. That’s how you know hip-hop has had a lasting effect onour society.

My dad wears a Sean John tie, not becauseit’s hip-hop, but because it’s good. That’s the only reason peoplewanted programmers to play hip-hop—because it was good. It was America.

Amy Laskowski can be reached at amlaskow@bu.edu.

This story appeared in the Winter-Spring 2011 issue of Bostonia.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.