Treating Tibet’s Traumatized

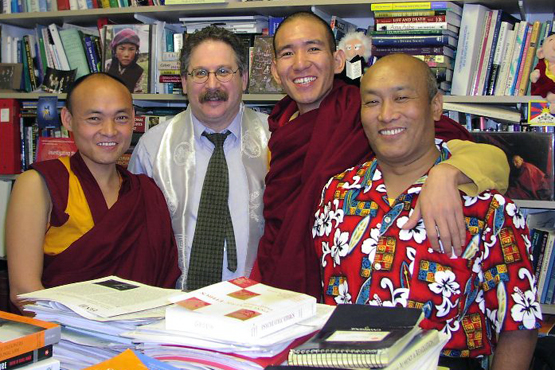

SPH’s Michael Grodin blends Eastern healing and Western medicine to help torture victims

After last summer’s Beijing Olympics, Michael Grodin’s monks were in trouble.

“When things happen in Tibet, it’s a crisis,” says Grodin, a psychiatrist and a professor of health law, bioethics, and human rights at BU’s School of Public Health. “When there were all those arrests, all of my monks started having flashbacks and nightmares.”

For the past 15 years, Grodin, who also teaches psychiatry and community medicine at the School of Medicine, has been treating a growing handful of Tibetan monks, survivors of Chinese prisons and prolonged torture who found their way to the United States and political asylum. To that end, Grodin created the Boston Center for Refugee Health and Human Rights (BCRHHR), which is based at Boston Medical Center and today treats some 500 clients from 50 countries, including sub-Saharan Africa, the former Yugoslavia, Latin America, Albania, southeast Asia, and Tibet, as well as Kurds from Turkey and Iraq.

The monks were diagnosed by their traditional healers as suffering from srog-rLung, roughly translated as a life-wind imbalance, which according to Tibetan medicine has the potential to develop into mental illness. Western doctors diagnosed them with a more familiar term: post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). With his 30-year background in treating survivors of trauma and torture and experience with Buddhism and Tibetan culture, Grodin took a mixed approach.

“After a while I was able to see the diagnosis, which is kind of a combination of homesickness, heartache, sadness, a mixture of depression and PTSD in Western terms,” he says. “It’s also a distinct sense of longing and guilt for being here with their fellow monks being back in Tibet, and missing their families. Then also a kind of rumination, constantly thinking about what’s going on in Tibet.”

In a paper published in the recent issue of Mental Health, Religion and Culture, Grodin and several BCRHHR colleagues describe the treatment he has employed, which integrates traditional Eastern techniques such as meditation, singing bowls, breathing exercises, and tai chi and qigong, with Western-style approaches like talk therapy and medication. BU Today asked Grodin whether the two medical hemispheres can productively coexist.

BU Today: How did you begin treating torture victims?

Grodin: I began my work with Holocaust survivors and became very interested in resiliency. I wondered why some people did well, some poorly. What’s protective, and what are the situations that allow people to be resilient? I think people focus too much on the negative and the bad things and not enough upon the positive, building on the strengths that people have. Most psychotherapy deals with people’s problems. I prefer to deal with strengths and what works and what was good in childhood. Let’s build on that.

What makes people resilient?

Factors such as early childhood upbringing, good object relations, a strong sense of self and ego structure, having a community that’s protective. Political activists who are arrested and tortured, but are part of a cause, do much better because they can somehow rationalize it. People who are taken off the streets and just tortured can’t make sense. People who are religious or have some kind of sense of meaning in the world, some kind of sense of purpose, tend to do better.

How did you come to work with Tibetan monks?

I was involved in the Tibetan community because of my activism around torture and what’s happening in China. About 15 years ago, I was asked if I would see one of the monks who had been imprisoned and tortured. I saw him and I was helpful, and then another monk came, and another. Next thing you know I was the center for all the monks. Because of my knowledge of Tibet and of Buddhism and my openness in working with Tibetan doctors and my experience with meditation, they became more comfortable coming to see me and trusted that this was a safe place.

What symptoms were they grappling with?

Meditation is a major part of their life and generally very comforting, so it was quite distressing for them that they were having flashbacks, to put it in Western psychiatric terms — meaning that they were reexperiencing what happened to them in prison — and so they would have vivid images, sometimes just anxiety, and a kind of hypervigilance, being on guard. Classic symptoms of PTSD.

If you have a tsunami, you have acute trauma and you have symptoms, but they are much easier to treat. But when you have Holocaust survivors or people in prison and they can’t escape, that causes enormous difficulties and develops what I call “soul death,” which is a lack of a sense of who they are — kind of the walking dead.

The other thing is the monks tended to dissociate from their bodies because they were being tortured. It’s like rape victims who have an out-of-body experience. We have to try and reconnect them with their bodies.

How do you treat them?

How do you treat them?

I do a lot of breathing exercises to recenter and recalm them, particularly when they get into these flashbacks. Breathing is a form of meditation. One of the things I think was going on was that the Tibetans who were doing the higher level kind of meditation were having a disinhibition. Their frontal lobes were keeping a hold on things and when they got into this deep meditative state, things opened up and all kinds of bad experiences and feelings came out. One of the things we’re finding with Holocaust survivors, who are very elderly now, is that as they start to develop dementia and strokes, they have a frontal release problem and get disinhibited and start to flash back and think they’re back in Auschwitz.

You also incorporate Western medicine?

Yes. I do psychotherapy. But I call it them coming to teach me about Buddhism. We meet. We talk. I listen. We do qigong, tai chi, we meditate together, practice some breathings and some mantras. And the singing bowls are wonderful, very calming and relaxing.

I also give them some antidepressants. For a while I was quite concerned about the interactions of my medicine with the herbs that the Tibetan doctors were giving them. The Dalai Lama’s physician was here once, and I went to meet him and brought the list of medications and the herbs. He said they were on too much of one compound or another. But I think the interaction between the two is pretty safe.

How do you communicate with the monks?

Through an interpreter mostly, though some of them have learned English. They know a lot more than they let on. The interpreters are in a very special situation because they’re privy to information that’s quite sensitive. There are some wonderful members of the Tibetan community who interpret and are very special and trusted.

Do you use any of the same approaches with non-Tibetan patients?

Yes, I do some of the bowls with the Africans. They love it. I did the qigong with a Kurd. In Latin America, it’s unacceptable to see a mental health provider because it’s not in their culture. So I go to the primary care clinic and I see them. They come and teach me about their country. We don’t call it therapy.

What about with Western patients?

I don’t treat Western patients, except for some Holocaust survivors, although I do some acupuncture treatment in the oncology department for people getting chemotherapy.

Do you find Western medicine becoming more receptive to Eastern healing?

I’ve practiced meditation for many years. I teach qigong and tai chi here at the medical school. I do acupressure, acupuncture, hypnosis. Some people call it alternative or complementary medicine. I call it integrated medicine. It’s funny to talk about it as alternative, because the Chinese have been doing it for 4,000 years. I would call that traditional and call Western medicine alternative. There’s been a growing acceptance, because it works, particularly for chronic illness and chronic disease, which Western medicine doesn’t do a very good job with.

What have you learned from the monks?

They’ve taught me about compassion. It’s an incredible thing that they have compassion toward their perpetrators. They’ve taught me loving kindness. They taught me about being present and being in the present. They taught me that we all go through struggles.

They’re very unusual. Very kind, very gentle. They’re great scholars. Some of them are like Ph.D.s in Buddhism, but they work here. One of the monks I care for sweeps the floors for a restaurant overnight. And he came to me and wanted to know if he was doing good job. Another one is a gardener. Another is a baker.

It’s been an incredible privilege and honor to work with these people, and hopefully I’ve helped them, too. My heart goes out to Tibet. What’s going on there is a horrible thing. What happened to these monks shouldn’t happen to anybody.

Caleb Daniloff can be reached at cdanilof@bu.edu.

Click here to listen to Terry Gross’ recent interview with Michael Grodin on NPR’s Fresh Air, where Grodin discusses the integrated treatment of torture survivors, including Tibetan monks.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.