Architectural Icon Gets Makeover

LAW tower was a tall order, delivered

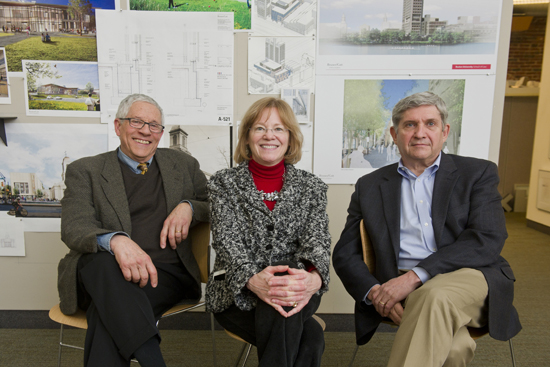

Leland Cott (from left), Lynne Brooks, and Peter Ziegler of the Cambridge architectural firm Bruner/Cott. The team designed the extensive exterior and interior renovations of the BU School of Law tower. Photo by Cydney Scott

Among the daily parade of students and faculty crossing campus in the shadow of the BU School of Law tower are some who wonder why the building, widely considered one of the less attractive on campus, is being so meticulously refurbished. Others, some who love it and some who don’t, acknowledge the structure’s iconic status as BU’s half-century-old beacon to those other universities across the river.

In fact, the building is an architectural treasure. At 18 stories high, it is one of a complex of circa 1960s buildings designed by the late Barcelona-born architect Josep Lluís Sert, a friend of Picasso and Miro, a protégé of Le Corbusier, and a 1939 refugee from the fascist Franco regime. Sert headed the Harvard School of Design from 1953 to 1969, where he was a mentor to Leland Cott of the Cambridge architectural firm Bruner/Cott, the firm that designed both the school’s renovated tower and the recently completed Sumner M. Redstone Building, which is merged with it. Sert’s bold designs, many employing unmasked reinforced concrete, include Harvard University’s Holyoke Center, now the Smith Campus Center, long the object of a love-hate relationship with those it dwarfs at ground zero of Harvard Square.

“We’re sort of infatuated with Sert,” says Cott, whose team on the BU LAW project includes principal architect Lynne Brooks and senior associate Peter Ziegler. Before it could tackle the tower’s weathered, poured-concrete exterior and cramped, dated interior, the firm “had to prove to BU, and to ourselves, that this was doable,” Cott says. “We had to reassure the dean that it was going to be okay, because a lot of people have bad memories of what it was like to be in the tower building, and they couldn’t see how it could be saved.”

“I think the single biggest design and programming realization we made was that the tower, with its very small square footage, was never really suited to being a good classroom building,” says Ziegler. “Very quickly we determined that it should not be a classroom building, but it would be one of the best administrative and faculty office buildings in the city, because of its size, its access to natural light, and its views up and down the river.” The architects got BU’s blessing to “let the tower be what it could be,” an office building, and put all of the assembly functions—classrooms, new social space, new space for clinical work—in a second, new academic building, which would become the Sumner Redstone Building, Cott says.

Today, the tower, with its lattice of external green and red panels restored to its original eye-popping shine, reflects Sert’s vision, while inside it meets the academic and human needs of its occupants far better than it had previously. “We are looking forward to the opening of the renovated law tower this summer, which will complete our construction and renovation project,” says Maureen O’Rourke, dean of LAW. “Once the LAW tower is back online, we will have new spaces for our student organizations and journals, clinical programs, library, and faculty and administrative offices. Most importantly, the tower will connect seamlessly to the Redstone Building and we will have the entire law school community back together again in one state-of-the-art complex.”

Designer of Mass MoCA in North Adams, Mass., and BU’s Yawkey Center for Student Services on Bay State Road, Cott is fond of quoting Winston Churchill on architecture: “We make our buildings, and our buildings make us.” It’s true, says Cott. “We have a different attitude about ourselves when we’re in a building that feels good and supports us.” Having the Sert tower do that was, so to speak, a tall order.

Built in a style often referred to as the brutalist (from the French béton brut, or “raw concrete”) school, the tower had fallen victim to the ravages of time on the outside, and never really suited its purpose inside. Chronic traffic jams in its six small and unnervingly slow elevators kept students waiting as long as 20 minutes to move between classes. The cross-ventilation and air conditioning systems were outmoded and the building lacked suitable meeting spaces. The awkward ground floor entrance was accessed from a wind-battered plaza (now downsized to welcoming landscaped gardens and paths) used only for foot traffic. The renovated tower and new Redstone Building now form a cohesive complex worthy of a law school founded in 1872, and that cohesive complex comes at a cost of $184 million, several million less than the price tag for a new facility in the same spot, according to Gary Nicksa, BU senior vice president for operations.

“We were charged with taking the vertical culture of the law tower and making it horizontal,” Cott says. That’s being done by revamping the tower with new mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems, larger bathrooms, and spacious modern facilities to house the school’s administrative departments, faculty offices, moot courtrooms, and writing programs.

The renovation is also being done in record time. BU officials “were originally looking at a four-year plan, where they were going to renovate the tower several floors at a time so some people could remain in the tower during construction,” says Brooks. “Even trying to renovate your house while you’re in it is a nightmare, so when we said, ‘If you move out, we can do this in one year,’ they agreed.”

“Before we got to it, the law school had no social space whatsoever,” Ziegler says. “As soon as class was over, students would leave and go to the GSU and stay there until their next class. They’d come and go by that little corner door.” With the Redstone Building complete, LAW students now have plenty of space. And light. And an inviting café, along with refrigerators and microwaves for brown baggers. The students linger, as do faculty, enjoying the river views, and there’s no longer the unnerving commuting time between classrooms, which are easily accessible from one other by elevator or stairs.

“The toughest sell was, frankly, internally, to try to do the best job we possibly could to work with Sert’s existing composition,” Cott says. “What I’m fond of saying is that the tower’s going to be better than it ever was.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.