Remembering Nelson Mandela

BU community weighs antiapartheid leader’s towering legacy

The world is mourning the loss of Nelson Mandela, winner of the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize, who spent a lifetime fighting racism and inequality. Mandela, 95, died yesterday at his Johannesburg home. The former African National Congress leader, once quoted as saying, “There is no easy walk to freedom anywhere,” was imprisoned for 27 years for his antiapartheid activism. Following his release in 1990, Mandela—a tireless advocate of peaceful reconciliation after apartheid’s dismantling—went on to become South Africa’s first black president, in 1994. He served one term, stepping down from office in 1999. One of Mandela’s daughters graduated from BU. Zenani Mandela Dlamini (MET’92) is the South African ambassador to Argentina.

BU Today asked several Africa scholars and others on campus to comment on Mandela’s life and enduring legacy.

John Thornton, College of Arts & Sciences professor of African American studies and history, author of Africa & Africans in the Formation of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800 (Cambridge University Press, 1992), Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500–1800 (Taylor and Francis, 2000), and coauthor with Linda Heywood of Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585–1660 (Cambridge University Press, 2007)

How often it is that an idealistic young man joins a cause about which he is passionate and sometimes sacrifices a great deal for it? This is not at all uncommon—graves are full of passionate young people ready to sacrifice their lives for what they believe in. But how common is it, also, for those passionate young people, having begun to effect the change they sought, to find themselves yielding to other pressures and gradually becoming as much a part of the problem they addressed as the solution they aspired to?

This is exactly what makes Nelson Mandela so remarkable and even close to unique. He, like so many other young South Africans, took on the obvious evil of apartheid and racism with passion and determination. And he, like so many others, made sacrifices on behalf of the cause—in his case not his life, but his liberty. Yet when he achieved the goal and was put in the presidential palace, he refused to fall into the trap of power and wealth. He remained steadfastly committed to that goal while president, and took that conviction so far as to step aside when he felt he could no longer pursue it with sufficient energy.

Linda Heywood, CAS professor of African American studies and history, author of Contested Power in Angola: 1840s to the Present (University of Rochester Press, 2000) and coauthor with John Thornton of Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585–1660 (Cambridge University Press, 2007)

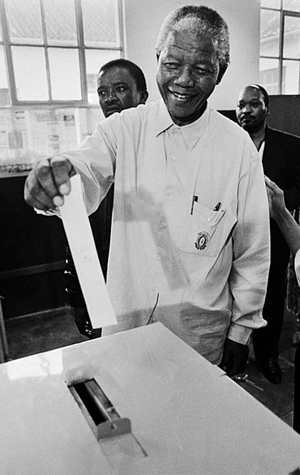

Nelson Mandela and his struggle to achieve justice for his people dominated my academic life during my second year as a graduate student in African history at Columbia University in 1974, when I was a research assistant working in a dingy basement in Harlem. I was leafing through newspaper clippings and papers of the Council on Africa, an African American organization formed in the 1950s by white and black scholars and political activists who started the first public campaign to get Americans involved in public agitation to bring an end to the apartheid system. It was from that research and graduate papers done on Angolan and South African history at Columbia that I developed my passion for the South African cause. I participated in many of the boycotts of South African products and the Free Mandela campaigns of the early 1970s. When Mandela was released, it was as if my own father had been unfairly imprisoned and was now free. I came to admire Mandela even more for never using the race card, but always talking about the law, human dignity, and rights. The sight of South Africans of every color lined up along miles of streets to exercise their right to vote is an image that will remain with me forever. This was all due to the courage of Nelson Mandela. I think we are indeed blessed to have had this angel among us.

Timothy Longman, director, African Studies Center, and CAS associate professor of political science, author of Christianity and Genocide in Rwanda (Cambridge University Press, 2009)

Nelson Mandela was an important figure for African politics because of how he acted in office—his decision not to seek vengeance against those who had imprisoned him and oppressed his people, his willingness to share power with former enemies, and ultimately his decision to step out of power voluntarily. Democracy and good governance are based more on good political practices than on laws and constitutions, and Mandela is a towering figure because he established the practices of limiting presidential power. In African politics, presidents who allow their power to be limited have been unfortunately rare, and Mandela’s willingness to do so helped launch South Africa on a positive political path.

Barbara B. Brown (GRS’71,’79), director of the Outreach Program, African Studies Center

Today, Nelson Mandela is revered as a saintly man who brought South Africa to freedom. But years ago, such a view was not widely shared in the United States. For starters, most people had never heard of him. From 1963 until 1990, he was in prison for treason. Many other Americans, including political and educational leaders, distrusted him as too “radical,” a man who consorted with communists and was prepared to take up arms, if necessary, for freedom. When he was freed from 27 years in prison, the acting president of BU lambasted the superintendent of the Chelsea schools for encouraging students to look to Mandela as a role model. Mandela, he said, did not serve freedom, but rather “has thrown in his lot with killers.” In 1988, President Reagan labeled Mandela’s political party “one of the world’s most notorious terrorist groups.” Six years later, that group, the African National Congress, easily won South Africa’s first free election and installed its leader, Nelson Mandela, as president. The world cheered, including those who had earlier and shortsightedly denigrated the ANC and Mandela.

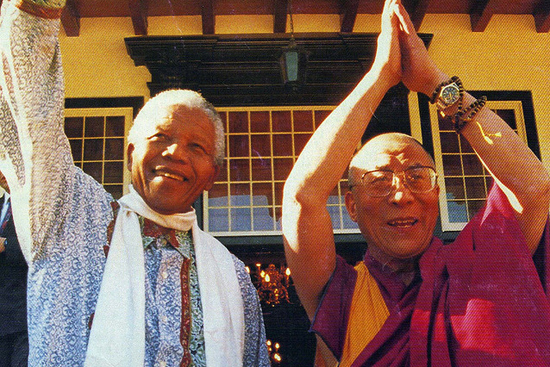

Happily, the world stopped fearing him and came to recognize his greatness. Against all odds, he was able to broker a hotly disputed end to apartheid. He sacrificed his personal life, because he believed that a world of human equality and dignity is possible. He did it all with grace, with firmness, and with his broad, handsome, smile. Thank you, Madiba.

Susan Griffin, CAS senior lecturer, romance studies

One of my abiding memories of Nelson Mandela from when I still lived in South Africa is that he was never too busy or too important for us little people. I volunteered for an organization back in the early 1990s, and we organized home and school exchanges between high school students of different races. This was at a time when both groups still knew very little about one another, and Soweto was considered a very dangerous place amongst most South African whites. Four of our students—two black and two white high school students—decided to stop by Nelson Mandela’s house in Soweto only a few weeks after his release from prison. They never dreamed that he would take the time to speak with them.

Kenneth Elmore (SED’87), Dean of Students

Nelson Mandela was the shining example of grace and dignity on this earth, with politics that tore at the limits of nonviolence within a surreal, dystopian society. He awakened my intellectual fire and later conquered a world.

His words, work, and persistence insisted that I be conscious. He was my Sengbe Pieh, Harriet Tubman, Ella Baker, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Angela Davis. He made me learn of front lines and about places I rarely considered—Angola, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Zambia, and Mozambique.

I am so glad I got to be present with him—a quick moment from within a crowd. I felt my heart banging and I cried. I’ll cry again.

Long live his spirit that gave me the first movement in which I felt I was an active participant. It pleases me that I will have deep memories of the time we lived on this earth together. Peace to Nelson Mandela.

Carl Hobert, School of Education lecturer and founder and executive director of the nonprofit Axis of Hope Center for International Conflict Management and Prevention

Mandela, spelled another way, is “Lead Man,” and this he was, is, and will be for millions of people in our shrinking world, now and for generations to come. During his 27 years of incarceration, he became known for his profound integrity and sacrifice on behalf of others. In his roles as former president, father, grandfather, and protector of others, and even when in poor health, he has continued to believe in serving and protecting others, forever, and he has done so with an eternal smile. For generations of children who will follow in his footsteps, he will be a visionary freedom fighter who knew how to inspire others as the humble leader of his cause. Just as so many millions believed for countless years, we must now declare: “Free Mandela.”

Dexter L. McCoy (COM’14), president, BU Student Government

The impact of Nelson Mandela’s life reaches far and wide. Before ascending to the office of president of South Africa, Mandela stood by his convictions, and after becoming president he still held true to them. His legacy will always be one of strength, courage, and a genuine love for the good of people. When faced with adversity, Mandela has taught the world to press on and follow their moral compass.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.