Regenerating the Soil Economy: Policy Insights from Northeastern Agriculture

By Eric Christine

As topsoil degradation and climate change threaten ecological habitats across the US and the world, transitioning toward sustainable farming practices is key to reducing the environmental impact of the global food system.

The Northeastern US currently ranks among the top regions in terms of adoption and current implementation of land use practices that promote soil health. Small and medium-sized farms often lead in adopting these practices, but they face various financial barriers. Current federal farm payments favor large commodity farms that are less likely to use regenerative practices. A focus on effective support for smaller farms to transition to sustainable practices is therefore essential.

The landscape of farms is changing in the Northeast, and policies aimed at incentivizing the implementation of soil health management practices can prove useful toward advancing the economy and environment. As the call for greater investment to aid farmers in transitioning toward regenerative practices gains momentum, the Northeast could be a model for federal policies that seek to enhance support for local producers across the nation.

The Economics of Soil Health Management Systems

A 2024 report analyzing the economics of soil health management practices published by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Forestry Service of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) outlined the importance of two distinct practices for sustaining the long-term productivity of US agriculture: cover crop usage and no-till farming. The tradeoffs for farmers are different for each practice, as cover crops may be used in tandem with no-tillage and vice versa. Conservation tillage is a related approach that uses some tillage but leaves more than 30 percent crop residue post-tillage.

Since 2017, the number of farms utilizing no-till and conservation tillage practices has increased by 4 percent and 9.8 percent, respectively, while cover crop use has decreased by 6.6 percent across 10 Northeastern states (Connecticut, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Number of Farms Using Selected Land Management Practices in 10 Northeastern US States, 2017 vs. 2022

Source: 2022 USDA Census of Agriculture. Chart generated in RStudio.

Tillage Practices

Conventional or intensive tillage involves breaking up the soil to prepare for planting crop seeds, mixing fertilizer into the soil, or to control weeds. The problem with this practice in the long run is that it contributes to soil degradation, reduced productivity and greenhouse gas emissions via machinery and release of sequestered carbon.

Alternative methods to conventional tillage such as conservation tillage or no-till have grown in popularity, especially in the Northeast. There are many private sector benefits to implementing either practice, such as reductions in labor, machinery and fuel costs plus improved nutrient recycling and water infiltration in the soil, helping to increase yields over time. According to the NRCS report, no-till systems appear to be among the least costly methods of crop production.

Moreover, the benefits of regenerative practices extend to the public through many mechanisms. No-till systems can enhance the sequestration of atmospheric carbon, reduce nitrogen and phosphorous runoff, and create a robust topsoil environment—promoting biodiversity and improving water quality.

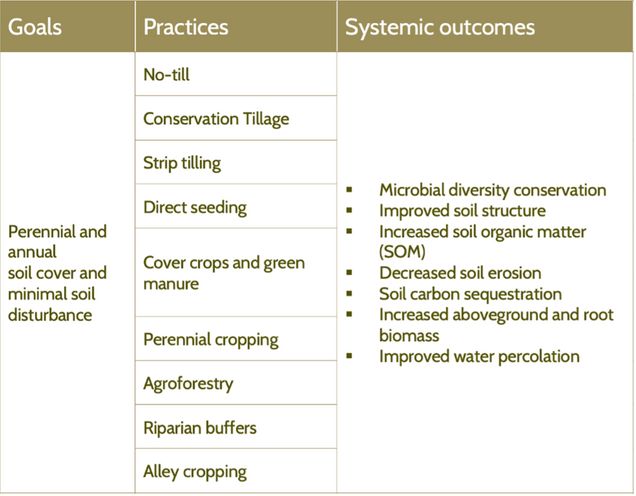

These observations echo those of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, which frame regenerative agriculture as essential to ecological resilience—highlighting practices like no-till and cover cropping as critical to global soil health and climate mitigation (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Systemic Outcomes of Healthy Soil Practices

Source: Adapted from Recarbonizing Global Soils: A technical manual of recommended sustainable soil management, FAO 2021.

Cover Crops

Cover crops are plants grown primarily to protect and improve the soil between periods of regular crop production, typically not harvested for distribution. Crops such as legumes (soybeans, alfalfa, peas, etc.) are favored for their ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen, allowing more nutrient bioavailability for cash crops. The NRCS report found difficulty in examining the costs and benefits of cover crop implementation given limited research, identifying a need to invest more in this field.

Figure 3: Percentage of Cropland in Cover Crops in the US, 2017

Source: Adapted from Economics of soil health management systems that sequester carbon: key research needs for the northeastern United States, Rejesus et al. 2024.

A 2023 study analyzing farming practices in four Northeastern US states found that incentives programs generally promote cover crop adoption—cover crop use persisted even after the termination of short-term financial support. The report also found that male farmers who operated larger, conventional farms were more amenable to cover crop adoption. The article concludes that:

“Evaluating participation is important for optimizing incentive programs and recruiting farmers who have been underrepresented in existing programs, including new and beginning farmers, women farmers and farmers operating smaller farms and organic farms.”

Assawaga Farm: A Model for Regenerative Practices in the Northeast

Assawaga Farm is a small, organic producer of vegetables located in Putnam, Connecticut. The farm incorporates a range of cover crops, produces a variety of crops for sale and utilizes no-till agriculture without herbicides—an important distinction since many large no-till producers use herbicides to kill off their crops. Despite no participation in government-sponsored cost-sharing programs or crop insurance, the farm remains profitable due to steady local demand and a diverse crop portfolio.

Through diversification, Assawaga Farm naturally minimizes the risk of lower yields. According to co-owner Yoko Takemura, “[t]he reason why a lot of vegetable farms are diversified is so that if one crop doesn’t do well, another crop is probably going to do really well, so… every year, we get better, the soil gets better, the crops grow better.”

The combination of regenerative practices at Assawaga Farm serves as a model for the regional expansion of cover crop adoption and no-till implementation. Besides supporting the transition of current farmers, policies must allow support for new farmers as well. As Yoko explains, access to land remains one of the greatest barriers for new farmers: “[l]and is the biggest issue… It’s very expensive, and there aren’t many options.” She also acknowledges that her and her husband, Alex Carpenter, were lucky to purchase their land before the COVID-19 pandemic, after which land prices had increased.

Trends in the Northeastern US

Figure 4 shows the distribution of farms in the Northeast by size. Small and medium-size farms predominate overall, but in recent years their numbers have declined while farms over 1,000 acres represent the fastest-growing category in the region.

Figure 4. Farm Size Distribution by Acreage Across 10 Northeastern US States, 2017 vs 2022

Source: 2022 USDA Census of Agriculture. Chart generated in RStudio.

Farms over 1,000 acres typically focus on a narrow range of commodity crops (corn, soybeans, wheat, etc.). In contrast, the smaller operations declining in number are far more likely to employ regenerative practices, prioritizing diversification of crops and soil health. Larger farms are generally male-operated, incorporate conventional tillage, and have less diversity in terms of crops grown. Current incentives programs tend to favor large farms and disadvantage smaller producers in the Northeastern US.

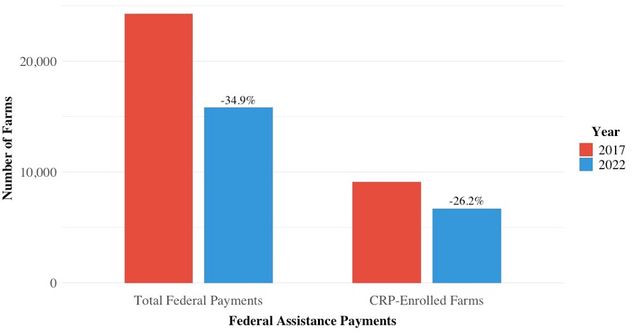

As the NCRS report and the 2023 study suggest, cost-sharing programs play an important role in cover crop adoption and the implementation of other soil health maintenance practices like conservation tillage or no-till. Questions regarding the role of such programs in the context of adoption within the Northeastern US are critical moving forward. As it stands now, producers across the region are receiving substantially less federal support relative to 2017.

Figure 5: Northeastern US Farms Receiving Federal Assistance Payments, 2017 and 2022

Source: 2022 USDA Census of Agriculture. Chart generated in RStudio.

Even as some conservation practices expanded between 2017 and 2022, the decline in cover crop adoption and the shrinking number of small and mid-sized farms suggest that financial problems —exacerbated by pandemic-era increases in land prices and input costs—may have constrained sustainable transitions. The expansion of 1,000+ acre operations raise further questions about the future of land access and resilience in the region’s agricultural system.

Policy Recommendations

Farmers typically bear the entirety of the costs of the labor, land and cover crop use associated with sustainable farming. Yet there are numerous societal benefits reaped (literally and figuratively) from conservation tillage and cover crop use: reduced carbon emissions, less nitrogen and phosphorous runoff in water bodies, enhanced water infiltration and increased biodiversity. Thus, increasing fiscal incentives for farmers to adopt optimal soil health management practices will not only boost the resilience of the region’s soil and improve the quality of the crops produced but also provide broader social and environmental benefits.

Greater public investment in research and data collection is essential for supporting the transition to regenerative practices. This investment can generate valuable information to support farming approaches that incorporate cover crops, no-till systems and organic farming. It can also foster public understanding of the importance of transitioning to sustainable farming. Maintaining and increasing funds allocated to programs like Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education must remain a policy priority to encourage independent research regarding the transition to regenerative agriculture, which is also a public good.

The US Farm Bill, currently set to expire on September 30, 2025, provides an opportunity for policymakers to strengthen incentives programs designed for the Northeast as well as other US agricultural areas. Of course, states and individual farms have unique needs, meaning that programs must be nuanced and tailored to help transitioning or beginning farmers.

One promising policy pathway is to create clear environmental cross-compliance standards for federal cost-sharing programs, ensuring that financial assistance payments are directly linked to regenerative practices that improve soil health. Through programs like the Environmental Quality Incentives Program, which currently offers financial assistance on a voluntary basis, financial aid could be conditioned on the implementation of soil health management best practices such as no-till or cover cropping, which are extensively utilized in the Northeast. Other policy options include expanding land transition incentives and low-interest loans for beginning farmers, addressing key financial barriers for small and medium-sized operations.

As Assawaga Farm demonstrates, regenerative practices are both sustainable and profitable—yet remain too often unsupported. Redirecting incentives to prioritize farms that adopt regenerative practices presents an opportunity to optimize soil health, support local agriculture and secure a resilient food system for the future.

Some organizations and initiatives currently working towards good policies for healthy soils in the Northeast are:

- Northeast Healthy Soils Network

- Northeast Organic Farming Association

- Northeast Healthy Soil Network Conferences

- Food Solutions New England

Eric Christine is a Master of Public Health candidate at Boston University specializing in food policy and sustainable agriculture.

*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Economics in Context newsletter.