Getting to Net Zero: Can We Do It?

By Stacey Yuen

In advance of the upcoming November climate summit in Glasgow, President Joe Biden has pledged to slash US greenhouse gas emissions by 50 percent by 2030, and 100 percent by 2050 − a marked departure from the climate denialism that characterized much of his predecessor’s term. With that commitment, the US now joins the ranks of major global players like the U.K. and European Union, which have vowed to cut emissions by 68 and 55 percent, respectively, by 2030. The global effort to reach net zero emissions by 2050 is critical for avoiding the worst impacts of climate change, but a key question remains: Can countries do it, and if so, how?

For Dr. Jonathan Harris, a senior research fellow at the Economics in Context Initiative who specializes in the macroeconomics of global climate change, the numbers speak a resounding “yes” for the US context. Speaking at the Dimensions of Sustainability Earth Day Symposium 2021 organized by the University of Massachusetts Boston, Harris analyzed the feasibility of implementing a Green New Deal in the US, its potential impact on emissions and the American workforce and the costs of implementation.

A (Surprisingly) Strong Start

What are the prospects for a Green New Deal to transform the US economy and to keep it operating in tandem with the country’s climate goals? Harris observed that the US has, encouragingly, been on track to meet the emission reduction target of 26-28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025 that was set as part of the 2015 Paris Agreement.

“Surprisingly, we are actually meeting those targets,” Harris said. “Obviously, this does not have to do with any kind of deliberate policy under the Trump administration. But just through the increase in renewable energy, cutback in coal and improved efficiency,” net emissions per year are already decreasing (see Figure 1 below).

As of 2020, the US had actually exceeded its emissions goal set under the 2009 Copenhagen Accord of 17 percent below 2005 levels in 2020. Emissions in 2020 were 21 percent below 2005 levels, although that result should not be taken as definitive, due to the general slowdown in activity caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, emission levels are already rebounding with recovery. Nonetheless, net zero remains a viable goal because, despite having the “worst possible policies” under Trump’s administration, “we are somewhat on track,” Harris said.

Figure 1: US Emissions Targets, 2015

Note: In 2018, actual US emissions were 10 percent below 1995 levels. In 2020, due to the covid-19 crisis, emissions were 21 percent below 2005 levels.

But how?

Harris identified several major developments that are already underway, but need to be accelerated to achieve the US’s net zero goal.

First, wind, solar and geothermal energy industries need to expand drastically. These industries currently provide about a third of the 11 percent of primary energy consumption that comes from renewable energy sources (the other two thirds come from biomass and hydroelectric energy). Wind, solar and geothermal industries should eventually replace the fossil fuel sector, which currently supplies 69 percent of total energy consumption in the US

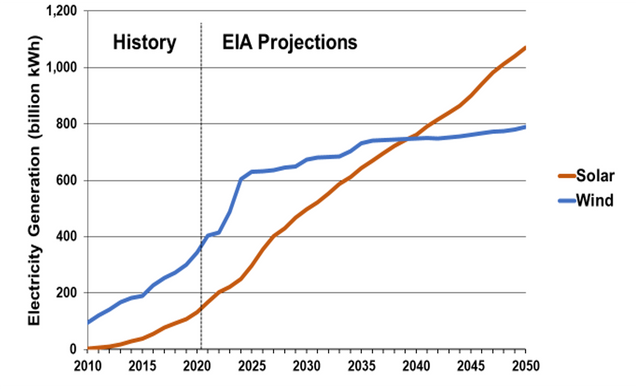

Thus far, there has been a rapid growth in installed wind and solar capacity that will only continue to rise significantly, according to projections by the US Department of Energy. Based on conservative estimates that do not take into account aggressive policy changes, the energy generated from wind and solar sources is likely to increase by two and six times, respectively, by 2050 (see Figure 2 below). Without subsidies, wind and solar are already the lowest-cost energy source globally, and account for about 70 percent of new installed capacity in the US and worldwide, Harris said.

Figure 2: US Electricity Generation from Wind and Solar

To achieve these goals, the US needs to expand the capacity of its electric grid by approximately 60 percent by 2030 to handle the vast amounts of wind and solar power. Vehicles and home heating systems need to be electrified: by 2030, electric vehicles’ (EVs) contribution to new car sales need to increase from its current 2 percent to at least 50 percent, while the percentage of homes that employ energy-efficient electric heat pumps need to double from current numbers to hit almost a quarter. The example of Norway illuminates the way forward: as of 2021, EVs accounted for 54 percent of sales in Norway, with an 83 percent share including hybrid vehicles. Sales of gas-powered vehicles in Norway declined from 71 to 17 percent in just five years, signaling that the path ahead for the US, while challenging, is not unrealistic.

In addition to expanding renewables, about half of the job of cutting emissions depends on ratcheting up energy efficiency. Citing a 2017 study by the International Renewable Energy Agency, Harris observed that reaching net zero by 2050 could be accomplished with 50 percent of the carbon reduction coming from a transition to renewable energy and 45 percent from energy efficiency gains. In other words, lowering the ceiling of total energy demand is just as critical as raising the floor of renewable energy supply.

Finally, the aforementioned innovations need to be coupled with robust efforts to halt the destruction of forests and allow secondary forests to grow. Forests already remove 29 percent annual anthropogenic carbon emissions. On a global basis, halting forest destruction and land-use change and allowing secondary forests to grow could sequester more than 90 percent of the current gap between emissions and removal rates, Harris said, citing a 2018 study.

Selling the Deal to Americans

Estimates of tens of trillions of dollars to implement the Green New Deal are misleading, Harris said. Although trillions in investments will eventually be required, critics overlook the economic principle of increasing marginal cost: a McKinsey study found that the costs of abating up to a third of total emissions are actually negative, then the next third is relatively low (see Figure 3 below). Initial efforts will largely involve increasing efficiency.

Figure 3: Global Greenhouse Gas Abatement Cost Curve for 2030

In fact, the plan could be “politically very popular” if handled well, according to Harris. Notably, worldwide, investments in clean energy already generate significantly more jobs than fossil fuel investments (see Figure 4 below). Providing rebates to lower-income groups could ensure that these individuals do not get disproportionally hit by a carbon tax, or could be designed to have a redistributive impact so that they actually comparatively benefit, Harris said.

Figure 4: Jobs Generated by Investing One Million Dollars in Clean Energy versus Fossil Fuel Production

Financing the plan will require policies that include raising revenue through raising corporate taxes, repealing Trump’s tax cuts on wealthy individuals, closing inefficient tax loopholes and eliminating fossil fuel subsidies. However, the private market does not appear “too concerned” for now, Harris said, citing the market’s quick rebound from its 1 percent dip following Biden’s announcement on raising corporate taxes.

Deficit spending may also be feasible, particularly when looking at debt as percentage of future GDP, Harris suggested. If you value the US economy like a company, using a discounted cash flow analysis, the debt to GDP ratio is just 0.7 percent, the lowest since 2004. The tremendous benefits of cutting emissions and avoiding catastrophic global warming – an estimated $23 trillion, according to the major reinsurance company Swiss Re – suggests that running up a current deficit should not pose a major problem.

The cost of cutting emissions will increase quite significantly the closer the US comes to net zero. But, as Harris noted, moving with the beneficial policies first and obtaining the large employment benefits of a Green New Deal will make the effort both politically and environmentally sustainable.

*

Never miss an update: Sign up to receive ECI’s newsletter.