A BU Center to Promote Cleaner Cities?

Just one idea proposed at Smarter Cities conference

BU Today article by Rich Barlow

As both an engineer and a motorist, Christos Cassandras feels the pain of drivers on Commonwealth Avenue. Although he usually leaves work after the evening rush has waned, he invariably hits a red light at the BU Bridge, even when there’s no traffic coming on the cross street. After that, it’s one red light after another along the avenue with its synchronized traffic lights—“just to make my life as miserable as possible.”

Wouldn’t it be nice if communicating “smart” lights could sense when there’s no oncoming traffic and wave you through, the College of Engineering professor mused to a packed house attending Wednesday’s Smarter Cities conference at the Photonics Center. That dream could be realized someday by the nascent technologies Boston and other cities are pioneering to collect, analyze, and act on data such as traffic counts, according to Cassandras and other speakers.

In fact, we already have a high-tech version of the old-fashioned parking garage. Cassandras, who teaches electrical and computer engineering, said data shows motorists in major urban downtowns, including Boston’s, cruise an average of eight minutes in search of a parking space. BU has one garage linked to a “smart” parking system: motorists can check an app on their handheld devices to see if there’s an open space in the garage. (Reserving it, however, is one bug that still remains to be ironed out, Cassandras said.)

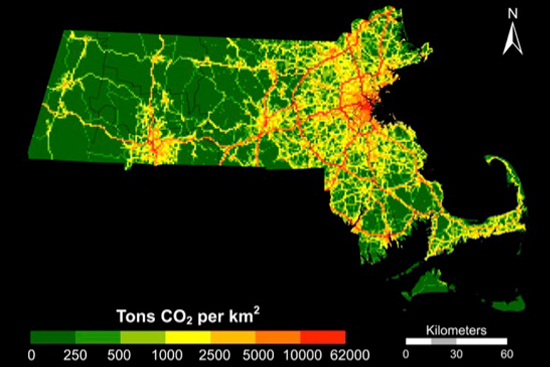

IBM bankrolled the conference as part of its Smarter Cities program, which supports data gathering to improve environmental, health, safety, and productivity initiatives in communities where company employees work and live. Lucy Hutyra, a College of Arts & Sciences assistant professor of earth and environment, is working with a grant from the IBM program to calculate better traffic counts in Boston and their related greenhouse gas emissions, which foster climate change.

Tag-teaming with Cassandras on his presentation to the assemblage of BU, IBM, and municipal leaders, Hutyra proposed creating a center or institute at the University to study and coordinate projects in environmental sustainability.

Boston has cut its greenhouse gas emissions to 7 percent below the 1990 levels, and Mayor Thomas Menino (Hon.’01) has targeted a reduction of 25 percent below that year’s levels over the next seven years. Statewide, Massachusetts hopes for a whopping 80 percent cut in emissions by 2050. The problem, Hutyra said in an interview, is that current emissions counts aren’t very good: they’re based on taking gas consumption and industrial activities and estimating average emissions resulting from each. Traffic counts are used occasionally as well, she said, although they aren’t conducted frequently enough to be of much value. She said that depending on who’s measuring, current emission estimates for Massachusetts can vary by as much as 40 percent.

“Nobody’s trying to cheat,” Hutyra said. It’s just that “we need better verification.” That could be achieved with laser spectroscopy technology that measures emission levels directly in the atmosphere; BU has such a sensor atop CAS measuring carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas. It’s part of a network of half a dozen sensors that BU and Harvard colleagues have established.

A center would enable government-corporate-academic partnerships, such as her Smarter Cities project, to “be more than one-offs—be something that is sustainable and something that can grow and evolve over time,” Hutyra said. She has discussed her idea for such a center with ENG Dean Kenneth Lutchen, another conference speaker, who expressed support in an interview.

“I think there’s a tremendous opportunity to create an integrated center or institute,” he said. “It would be a University-wide hub institute, which would have coalitions and partnerships with the private sector and government.” Budgeting such a center would require “a foundation or a company or a benefactor,” and “in order to make that work, you need one or more iconic, visionary faculty leader to help coordinate it.

“The next step is to identify how the key stakeholders would like to integrate and work at a University hub institute or center,” Lutchen said, “and identify what should be the portion of it that the University has to ante up, both with some staff resources and faculty time, and what should be the contributions from external constituents such as companies, foundations, or perhaps government funding.…I think we’re potentially a year or maybe two away from a major center.”

He noted that BU’s Sustainable Neighborhood Laboratory (SNL) already works with IBM, the city, and other businesses to make Boston “smarter.” For example, SNL and partners are working to collect and analyze data about energy use in Boston residential buildings and hotels to improve energy efficiency. One result: the Lenox Hotel recently installed energy-efficient windows, lighting, and insulation.

In another project, SNL is working with Roxbury’s Madison Park Development Corp., which operates more than 1,000 housing units for low-income Bostonians, to study energy use in those homes and how to make them more efficient.