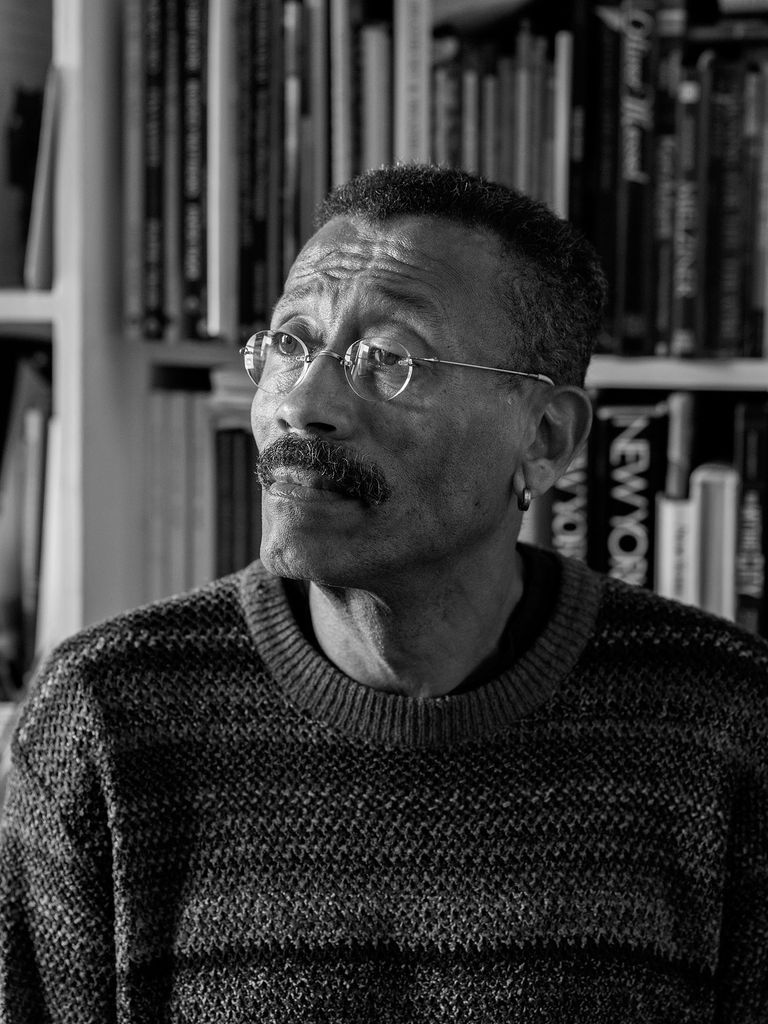

The “Hidden Figure” Bringing Hollywood scripts to Life: CFA Alum and Production Designer Wynn Thomas

For more than 40 years, alum Wynn Thomas has created the look for films such as Malcolm X, A Beautiful Mind, and Hidden Figures. This fall, he was recognized with an honorary Oscar.

The “Hidden Figure” Bringing Hollywood Scripts to

For more than 40 years, alum Wynn Thomas has created the look for films such as Malcolm X, A Beautiful Mind, and Hidden Figures. This fall, he was recognized with an honorary Oscar.

Production designers like Wynn Thomas (CFA’75) play a crucial role on a film set, working closely with the director to establish the visual concept—the mood, atmosphere, color, and composition—and then making sure the movie adheres to that look and feel throughout filming.

If you’ve been to the movies in the last 40 years, chances are you’ve seen Wynn Thomas’ work on the big screen.

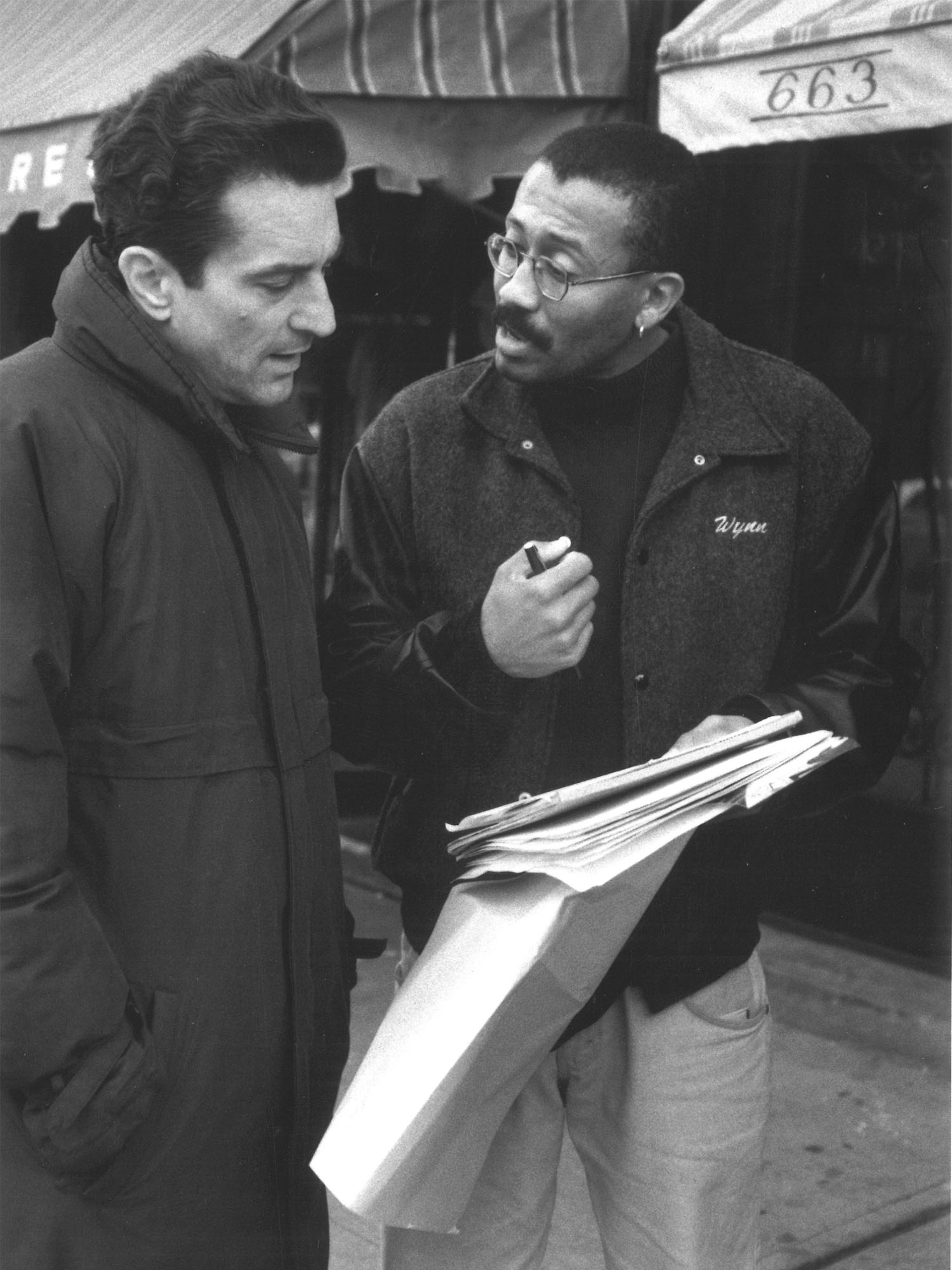

As one of the film industry’s most respected production designers, Thomas (CFA’75) has created the visual look for such acclaimed movies as Do the Right Thing, Malcolm X, Mars Attacks!, A Beautiful Mind, Cinderella Man, A Bronx Tale, and Hidden Figures, collaborating with directors like Spike Lee, Tim Burton, Robert De Niro, and Ron Howard.

“The production designer is responsible for taking the writer’s words and turning them into concrete images,” says Thomas. “No one else on a film does that. We illustrate the film, we formulate the look of the movie.”

Over the course of his decades-long career, Thomas has designed an art deco jazz nightclub for Mo’ Better Blues, created the unforgettable spaceship in Mars Attacks!, and recreated Vietnam’s famous Mỹ Sơn temple complex for Da 5 Bloods, shot in Thailand. Directors routinely praise his attention to detail, his gift for collaboration, and the way his designs enhance a film’s storytelling and emotional arc.

Despite having worked on more than 40 movies, Thomas has never been nominated for an Academy Award. “I knew that the work was good,” he says. “I just came to terms with the fact that it wasn’t going to happen for me.”

Until now. This summer, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) announced that Thomas would receive an honorary Oscar at the Academy’s 16th Governors Awards in November. This year’s other honorees were actor Tom Cruise, director and choreographer Debbie Allen, and singer-songwriter and actor Dolly Parton. The award is given “to honor extraordinary distinction in lifetime achievement, exceptional contributions to the state of motion picture arts and sciences in any discipline, or for outstanding service to the Academy,” according to AMPAS.

“Production designer Wynn Thomas has brought some of the most enduring films to life through a visionary eye and mastery of his craft,” AMPAS president Janet Yang said in announcing his award.

Thomas is only the second production designer in history to receive an honorary Oscar. (Robert Boyle, who worked on many of Alfred Hitchcock’s films as well as Fiddler on the Roof, was the first, in 2008.)

“I’ve been pinching myself, saying, ‘Oh, my gosh, I’m going to have an Oscar in the fall,’” Thomas says. “It’s fantastic to have the work recognized—the contributions I’ve made to the film business recognized. And it’s recognition for all of the incredible craftsmen and craftswomen I’ve collaborated with for the last 40 years. It’s a thrill to share this moment with them.”

Asking Three Questions at the Start

A production designer plays a crucial role on a film set, working closely with the director during preproduction to establish the visual concept—the mood, atmosphere, color, and composition—and then making sure the film adheres to that look and feel throughout filming. They hire and manage the entire art department, a staff that can number more than 100 and will include set designers, illustrators, graphic artists, props people, makeup artists, special effects supervisors, and production scouts.

Thomas says he asks himself three questions at the start of each project: “How do I feel? What do I want the audience to feel? And what do I want the actors to feel?”

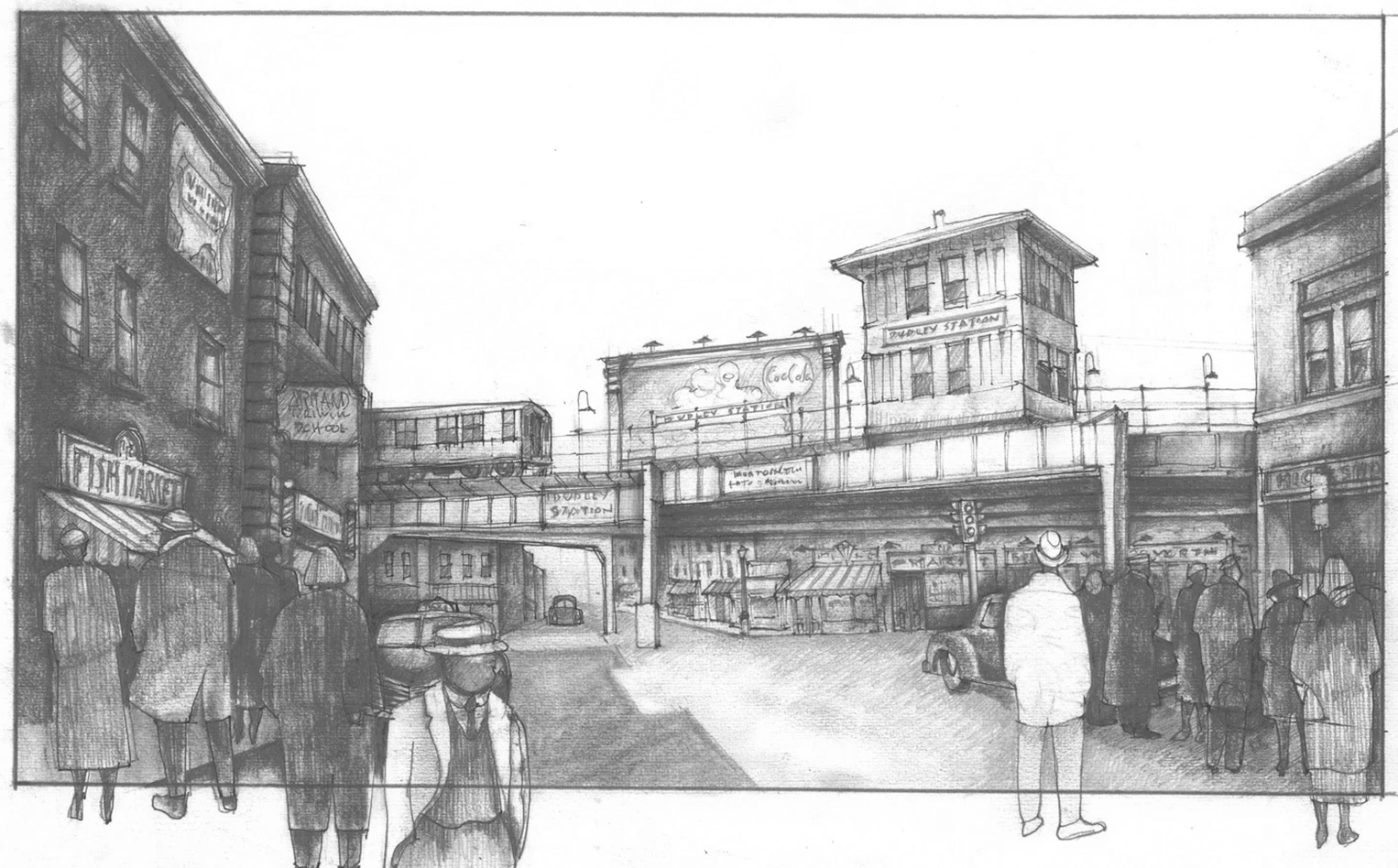

Perhaps no film better illustrates that approach than Malcolm X, which traces the life of the civil rights activist and Black nationalist leader from his early years serving time for grand larceny to his presence on the national political stage before being assassinated in 1965.

Thomas prefers to design using pencil and paper, as he did with the sketch (top) for Malcolm X. The scenes of Malcolm X’s early adulthood (left) have lots of color. For the scenes of him in jail (right), Thomas chose grays and pale greens. Clockwise, from top: courtesy of Wynn Thomas, Cinematic/Alamy.com, Maximum Film/Alamy.com

Thomas realized the film essentially unfolds in three sections. He decided that the first part—which includes Malcolm X’s early adulthood in Boston and his brush with crime, running an illegal numbers racket and committing a series of burglaries—would look like a 1940s Technicolor crime film, with extravagant sets and lots of color. The middle section, when Malcolm X is in jail and is introduced to the Muslim faith, chronicles his rebirth. For that section, Thomas drained most of the color from the sets. “It’s a series of grays and pale greens,” he says. And for the third act, he says, “when he has come into the assurances of his manhood, you’re surrounded by natural colors.”

Regardless of the project or the director, Thomas’ approach is always the same. After reading a script, he does extensive research, poring over the picture collection at the New York Public Library and in his home library, visiting museums and art collections, and paging through books. “Research does one of two things,” he says. “It either confirms what you’re already seeing in your head, or it will inspire you to take a different approach.”

For the film King Richard, a biopic about tennis stars Serena and Venus Williams and their family, Thomas wanted to know what their Los Angeles neighborhood looked like, what kind of food would have been on their pantry shelves.

“I look at a wide variety of images and resources and kind of fill up my body and soul with those images and then allow myself to form a conceptual approach to the film,” Thomas says. Once the director signs off on the visual concept, it’s distributed to everyone working on the film so that each person he’s collaborating with—costume designer, cinematographer, location scouts—is working within that framework.

Thomas says too many production designers today rely solely on the internet for their research, which is surprisingly limiting. “They’re all looking at the same thing, the same images,” he says. “The great thing about the library—not just the picture collections, but books—is that you’re seeing images that aren’t on the internet.”

And unlike many younger production designers, he prefers to design the old-fashioned way: using pencil and paper.

“All this stuff that I’ve stored up in my head comes out through my pencil. I can’t get it out through a computer. It has to travel through my body and come out through my pencil.”

After Thomas has articulated his ideas on paper, his team turns the set designs into computerized images.

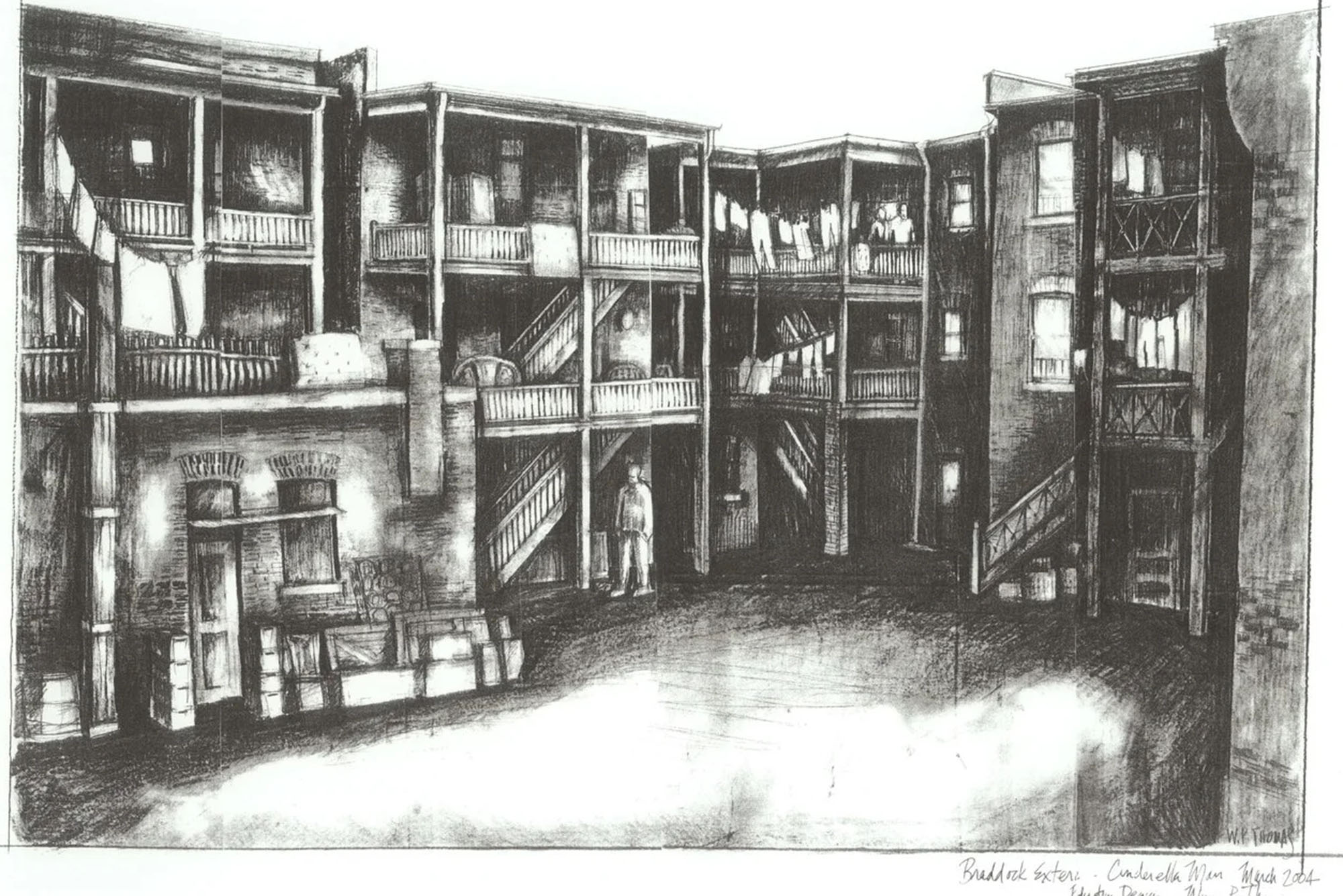

Successful production design helps to convey the emotional arc of a movie, Thomas says. For example, when designing Cinderella Man, the 2005 Ron Howard film starring Russell Crowe as real-life heavyweight boxing champion James J. Braddock, Thomas visited North Bergen, N.J., where Braddock had struggled to support his family during the Great Depression. “It had no emotional feeling for me,” Thomas says. So with the help of his location scouts, he began looking for architecture that was more reflective of the story. He put the family in an apartment with rough, stone walls and designed the exterior of the home so it existed in a back courtyard, surrounded by a series of porches that looked as though they were about to collapse on the family.

For the 2005 film Cinderella Man, Thomas designed the exterior of the home so it existed in a back courtyard, surrounded by a series of porches that looked as though they were about to collapse on the family. Photos courtesy of Wynn Thomas

Likewise, when designing the 2016 movie Hidden Figures—about three real-life Black female mathematicians who worked at NASA in 1961 during the height of the space race—Thomas was uninspired by the actual NASA facility where much of the action takes place. The Langley, Va., campus largely consisted of two-story, red brick, boxy buildings.

Thomas knew from his research that the story wasn’t just about a group of astronauts traveling into space. The main character, Katherine Johnson (played by Taraji P. Henson), is embarking on her own journey.

During location scouting on the campus of Morehouse College in Atlanta, Ga., where the film was to be shot, Thomas came across a building he immediately felt was right for the Space Task Group. “I went inside and discovered a huge, circular room, and I said, ‘This is it!’ I decided not to treat the space where she’s working as a realistic space, but to treat it as part of Katherine’s journey through space. She’s traveling down this long corridor, and she ends up going into a room that is essentially a big, huge globe. She’s on her own journey, just like the astronauts…. When she walks into that space, you want her to go, ‘Wow!’ There should be a moment of astonishment, because this is a world she’s never seen before.”

For the NASA facility where the main character in Hidden Figures works, Thomas created a huge circular room. “When she walks into that space, you want her to go, ‘Wow!’” he says. “There should be a moment of astonishment, because this is a world she’s never seen before.” Photo courtesy of Wynn Thomas (left) and Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy.com

The Road to the Oscars

Thomas had his own moment of astonishment when, as a 13-year-old, he watched the film adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ Summer and Smoke on television. “I was blown away by it,” he recalls. “There’s something about that movie that spoke to every fiber in my soul.” He headed to the local library in his Philadelphia neighborhood, devouring every Tennessee Williams play he could find. He got a job ushering at a local theater company, Society Hill Playhouse. Throughout high school, he spent nearly every day at the playhouse, stage-managing shows, running the box office, and acting in productions.

At the same time, Thomas was developing an interest in art. He was enrolled in a special art program at Overbrook High School, and when it came time to apply to colleges, he decided to combine his twin passions and become a set designer. He chose Boston University’s College of Fine Arts because of its strong theater program.

“The great thing about BU’s set design program was that it gave me a foundation to launch my career from,” Thomas says. “It taught me the basics of theatrical stage design. I learned how to draft, I learned about color, I learned about painting scenery.”

After graduation, he returned to Philadelphia, where he spent the next three years painting sets for the Philadelphia Drama Guild. After several years in his home city, he moved to New York and landed a job as set designer for the Negro Ensemble Company, the groundbreaking Black theater company. The company attracted a roster of talented young actors just launching their careers, including Denzel Washington and Phylicia Rashad. One day, an actor who had auditioned for the company but didn’t get in, and who happened to be an experienced carpenter, took a job building sets for Thomas. His name was Samuel L. Jackson.

Thomas also had a chance to work as a set designer on a couple of productions for the Public Theater in New York and at regional theaters like New Haven’s Long Wharf Theater, where he worked on the first production of David Mamet’s American Buffalo with Al Pacino.

But he soon felt pigeonholed. “I wanted to do Shakespeare,” he says. “I wanted to do musicals. But I was stuck doing Black theater, and I didn’t know how to deal with the issue.”

From stage to screen

In an effort to broaden his career options, Thomas joined United Scenic Artists, Local USA 829, so that he could work on Broadway and in film.

Richard Sylbert, an Oscar-winning production designer, was in New York to begin work on Francis Ford Coppola’s Cotton Club and was giving a lecture one evening, which Thomas attended. The next day, Thomas called the production office and told Sylbert he’d be willing to work for free on the film just to gain experience. Sylbert told him he had no openings in the art department, but reluctantly agreed to meet with him and look over his portfolio. During the meeting, he took Thomas on a tour of the set.

“It was a master class,” Thomas recalls. Sylbert offered to let him do some photographic research for him that day. A few hours later, Sylbert was told that Coppola needed models of every set in the film. Could Thomas handle the task? For the next six months, he built the models—and watched how a film gets made.

When The Cotton Club wrapped, Thomas moved on to the film Beat Street. He met Spike Lee, who had applied for the assistant director job. Lee didn’t get the post, but he and Thomas stayed in touch and, in 1986, Lee asked Thomas to be production designer on his groundbreaking film, She’s Gotta Have It. The film, shot in 10 days (everyone worked for free), was a huge hit at Cannes. It launched Lee’s career and a decades-long collaboration between director and production designer that included the films Do the Right Thing, Jungle Fever, Malcolm X, Crooklyn, and Inside Man.

Thomas says the two men share a kind of visual shorthand. “Sometimes there’s a connection that one makes with an artist,” he says. “And you can’t explain what that is, because it’s all organic and instinctual. That’s the connection we have.”

Now, after a lifetime of illustrating some of Hollywood’s most indelible films, Thomas says that receiving an Oscar is not only an affirmation of his own contributions to the industry. It’s also a reminder of how far he’s come.

“The American dream is still alive and well…. I’ve had a career telling some great stories, and I’m extremely thankful for that. That’s the great gift that my career has given me.”

Watch here as Wynn Thomas accepts his honorary Academy Award during the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Governors Awards ceremony on November 16, 2025.