Our Frankenstein Fascination, Explained by a BU Literature Scholar

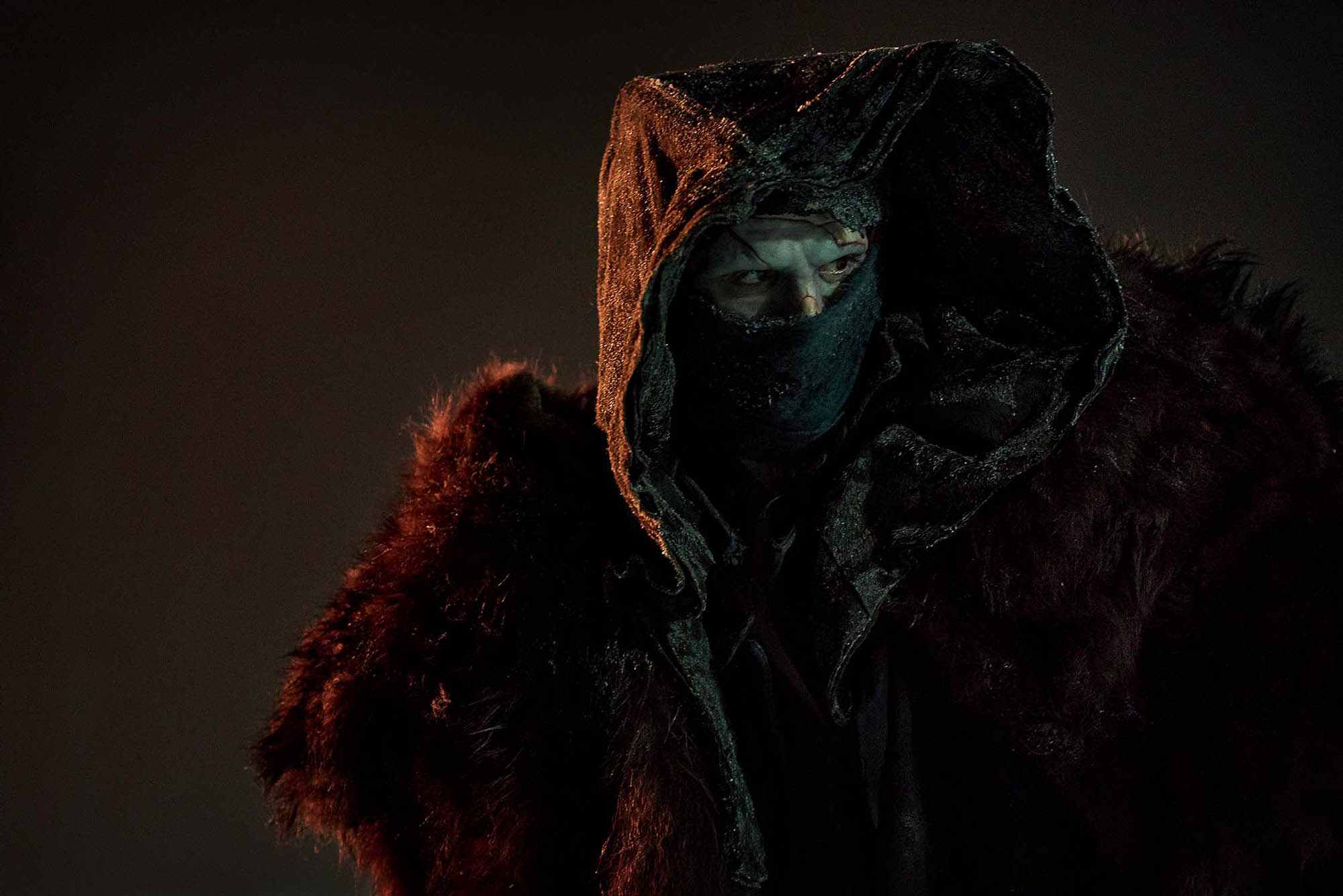

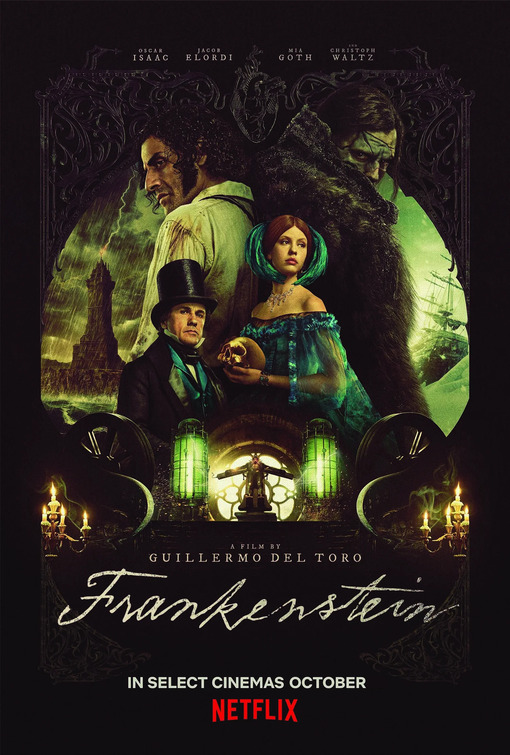

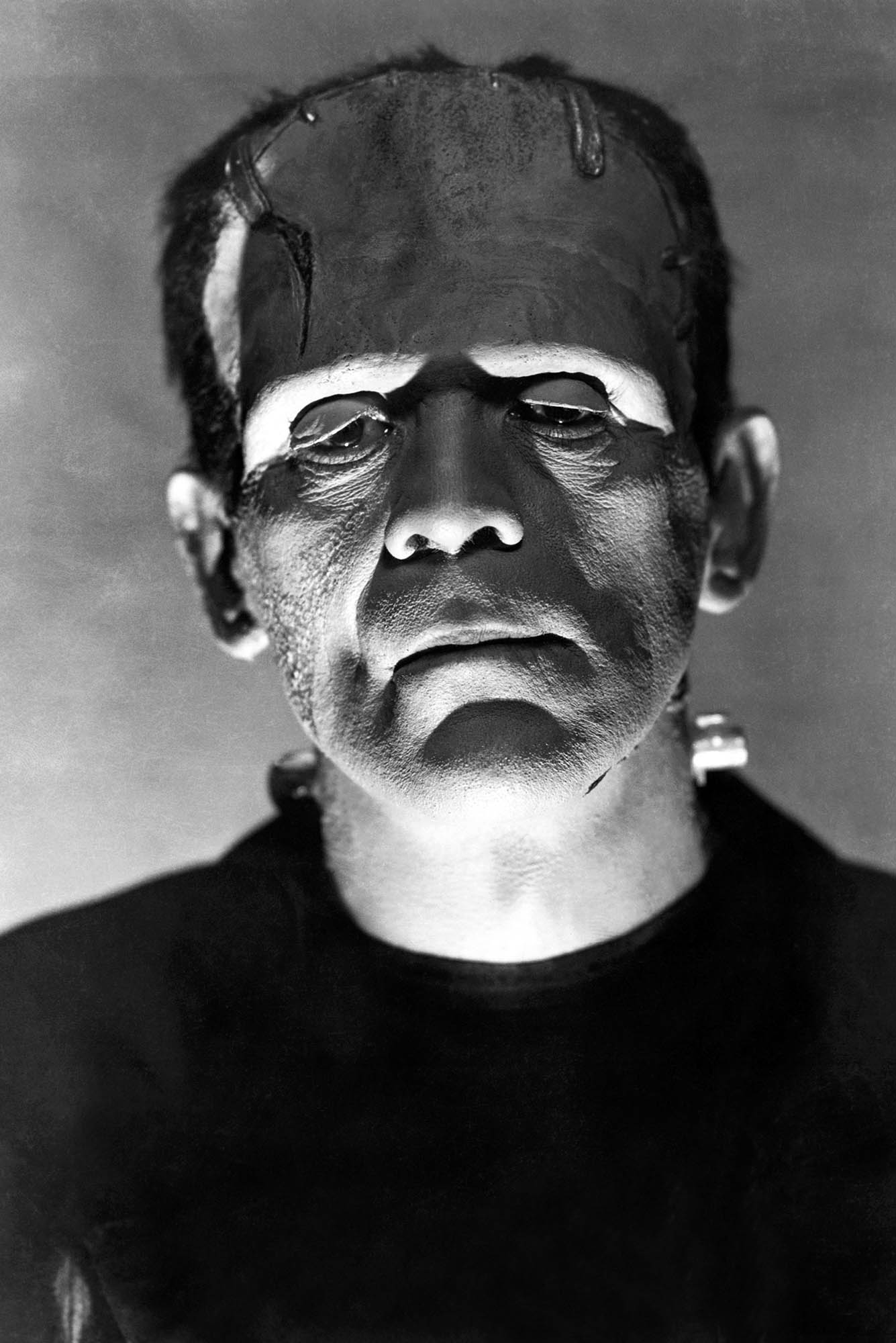

Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein is the latest adaptation of the iconic story, joining films like James Whale’s Frankenstein and Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Photo by Capital Pictures/Alamy

Our Frankenstein Fascination, Explained by a BU Literature Scholar

CAS lecturer Sarah Hanselman on Guillermo del Toro’s new movie adaptation—and why Mary Shelley’s story endures

Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein—another sweeping, gothic fairy tale from the Oscar-winning director—started streaming on Netflix in early November. It’s the latest in a long list of film adaptations of Mary Shelley’s landmark novel, joining 1931’s Boris Karloff–helmed Frankenstein, the 1974 cult favorite Young Frankenstein, and Kenneth Branagh’s 1994 iteration, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Del Toro’s version, starring Oscar Isaac as Victor Frankenstein and Jacob Elordi as the Creature, takes viewers from the frozen tundra to the halls of high society in Victorian England.

This Frankenstein hit Netflix’s number-one spot soon after its release and with over 33 million views, remains in the streamer’s top 10 list. The New York Times describes the film as “lush, melodramatic, sweepingly romantic, and achingly emotional.” That’s in part because of Elordi’s performance, which critics roundly call a standout. But it’s also because of del Toro’s signature lens, which has a way of illuminating the human behind the monstrous.

Ultimately, that is what Shelley’s story is all about, says Sarah Hanselman, a master lecturer in Boston University’s College of Arts & Sciences. Hanselman has a PhD in Victorian literature, and she teaches a Hub writing course on Frankenstein and its film adaptations for BU undergrads. She spoke with BU Today about del Toro’s movie and why we can’t get enough of Victor Frankenstein and his creation.

Q&A

with Sarah Hanselman

BU Today: What did you think of del Toro’s Frankenstein?

Sarah Hanselman: I really like the film. I think del Toro gets at the heart of Victor’s grandiosity and his inability to consider other people. This hubris that he has in the novel really comes across in the film. And I thought that the Creature was portrayed extremely sympathetically. You have a real sense of why he’s so angry. In the book, Shelley’s point is that there is a cost for reproduction. She herself had a child who died after a month, and her own mother died just after Shelley was born. So the parenting—and lack of parenting—thing is really front and center in the film.

What I see del Toro doing that I thought was really interesting is, how do you take these themes of loneliness and loss, parent-child—especially father-son—relationships, and make them speak to us now? The change he makes that I’ve just been chewing over is that he makes the Creature immortal. That is by far the most poignant expression, because the Creature is miserable: he’s lonely and he can’t die. And at the very end of the film, he walks off into the Arctic, and it’s just heartbreaking. I thought that was a really interesting twist on how to make contemporary audiences feel that desperation, that loneliness.

BU Today: What kinds of things does your class cover?

We start off by reading the novel. We talk a lot about narrative function—because the novel is shaped in a series of letters from a ship captain, Walton, describing how he and his crew found Victor Frankenstein in the Arctic, where he was chasing the Creature, after which Victor started telling Walton his life story. Part of the story Victor tells is how he remeets the Creature after a couple of years, and the Creature tells him his story. My students are always startled by how articulate and sympathetic the Creature is. A lot of them say that the Creature isn’t the monster; Victor is the monster for having abandoned him. So we have some really in-depth conversations about questions of education, nature versus nurture, parenting, abandonment, loneliness—all of these themes that the novel is really about. It’s not a horror story, except that to be lonely is horrible.

For the film adaptations, we look at James Whale’s Frankenstein and The Bride of Frankenstein. Then I have students present on four other adaptations: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Frankenweenie, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and Ex Machina. We talk a lot about what an adaptation is to begin with. We have conversations about: what’s a particular filmmaker trying to do? Who was the audience? What was the environment like [when the movie came out]? What are the directors getting right about the story, and what do you feel like they’ve really dropped the ball on?

BU Today: Do you have a favorite adaptation? Where does del Toro’s version fall, in your opinion?

I’d have to give it some space, because I saw this movie just recently and I don’t know if it’ll stand the test of time—but I think del Toro captures the themes of the novel most adequately. And he’s pretty true to the plot, which I appreciate. And he gives the Creature his voice; that really mattered to me. I liked the structure of the movie. I think this is probably the most faithful adaptation.

Kenneth Branagh’s version was also pretty faithful, but the central romance between Elizabeth and Victor [diverged from their more-modest storyline in the novel]. And I love the James Whale films, but they don’t bear any resemblance to the novel, really. And they have a lot to answer for, because that’s what everybody knows. If you ask my students at this point in the semester what comes to mind when they hear the word “Frankenstein,” they wouldn’t say, “a big, green, scary monster,” but that’s what they all say at the beginning of the class.

BU Today: Finally, what makes the story of Frankenstein so enduring? Why do we keep tuning in to remakes and reimaginings?

I often have students who want to take a psychological position on the novel for their research, and they start throwing around terms like “narcissist” and “attachment issues” and the like. Shelley didn’t have that language; she had that knowledge. We, as human beings, have not changed in the last 200 years. We still have the same drivers: we want love, we want acceptance. We’re still letting our science outrun our ethics. We still reject people who don’t look “right.” One of the things that I say to my students is, let’s be realistic here—we have a lot of sympathy for the Creature, but if he were to walk in the room right now, we’d be terrified.

So I think it’s a really remarkable novel in that way, that it really touches on all these very human emotions and experiences and foibles.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.