What a Southern Plantation’s Paper Trail Can Reveal About the Lasting Legacies of Slavery

Historian Mary Snyder (GRS’29) spent her summer building the archives of the Whitney Plantation’s store

Before her summer internship at the Whitney Plantation, Mary Snyder (GRS’29) worked for the Historic Charleston Foundation and Monticello, the home of founding father Thomas Jefferson. Photo by Sydney Joelle Walker

What a Southern Plantation’s Paper Trail Can Reveal About the Lasting Legacies of Slavery

BU historian Mary Snyder (GRS’29) spent her summer building the archives of the Whitney Plantation’s store

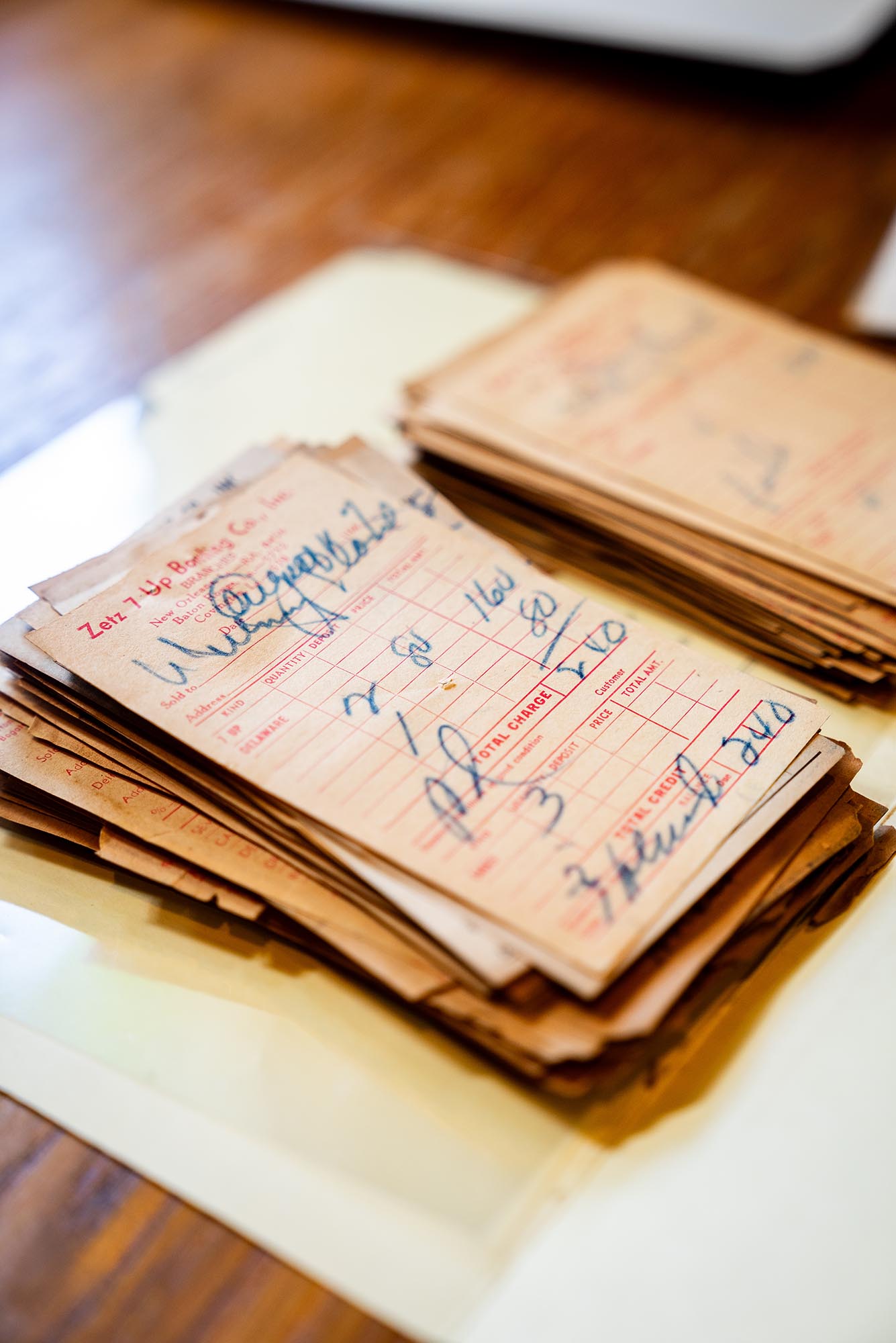

Rice (30 cents), oatmeal (20 cents), and meat (50 cents) all appear on Whitney Plantation worker John Johnson’s 1953 grocery bill. He spent $14.18 on 24 items, a balance carried over when he left Whitney to start a new job at a nearby plantation. “We understand that Johnson owns a balance of about $25,” his new manager wrote to his former boss. “Will you therefore bill me for the difference as soon as possible?”

This running total would continue to follow Johnson, indebting him to his bosses—just like thousands of other Black Americans who worked as sharecroppers on Southern plantations until the 1970s.

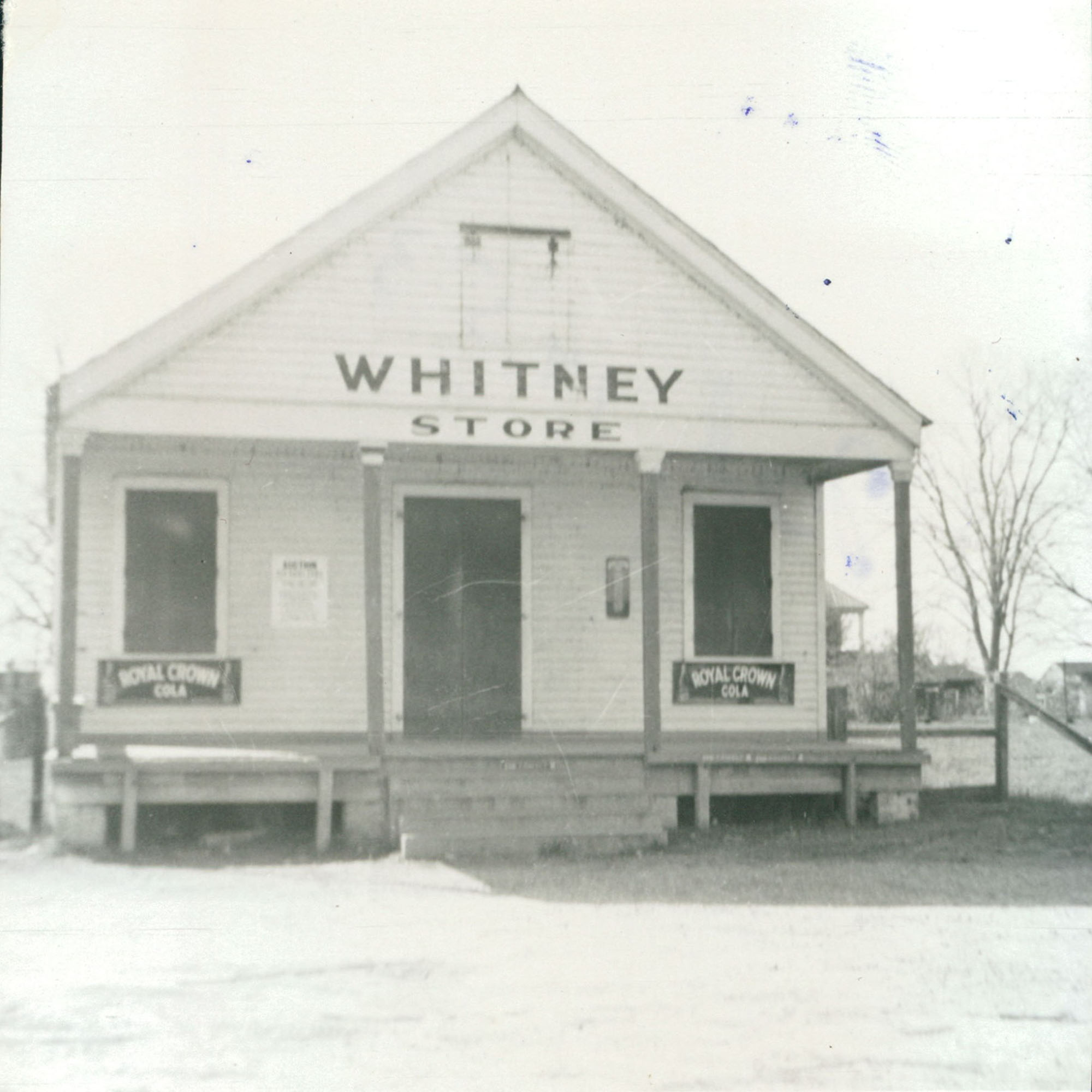

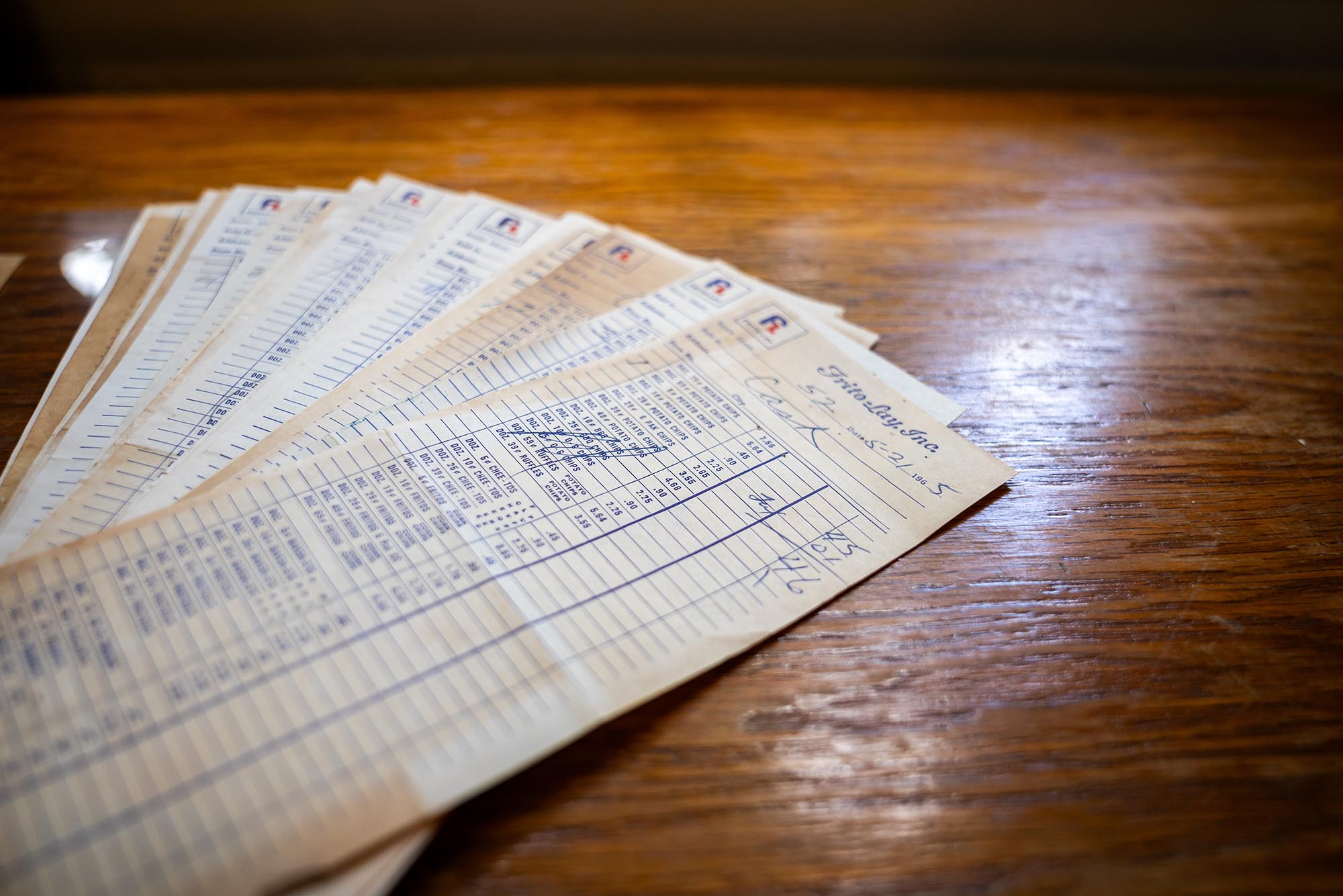

The bill and the letter are two of thousands of records studied by Boston University PhD student Mary Snyder, who spent her summer on the grounds of Whitney Plantation, now an historic site, on the banks of the Mississippi River in Louisiana, about an hour’s drive west of New Orleans. Snyder (GRS’29) pored over decades of handwritten receipts, tax returns, insurance claims, letters, and other documents from the Whitney Plantation’s store, which sold everything from clothing to medicine to groceries—and even handled workers’ personal affairs.

The records, Snyder says, tell an important story of the Jim Crow era. After emancipation, formerly enslaved workers often returned to plantations to work for low wages and in harsh conditions. Without money for housing or food, they had no choice. Plantation owners in turn set up stores, where the workers could buy groceries, medicine, clothing, and other items—usually at inflated prices and on a credit system. Anything the workers purchased from the store was subtracted from their paychecks at the end of the week. All of this prevented them from getting out of debt and moving off the plantation.

“Little has been written on wage-fixing in sugar plantations during this time frame,” says Snyder, a student in American and New England studies. “Many plantations don’t do an in-depth study of what happens to the site after Reconstruction.”

When Snyder took on the project, she wondered what records, like tax returns from the 1950s, could add to understanding the history of these grounds. Building on a decade of research performed by Whitney’s executive director, Ashley Rogers, Snyder’s 12-week internship involved cataloging 52 boxes of documents that, in the future, will be digitized and available to researchers.

“The collection provides an understanding of the legacies of slavery in that transformation: postbellum into Jim Crow into the civil rights era,” Snyder says. “We have a tendency to jump from the period of enslavement right into the present day, or we’ll talk about Jim Crow, but we don’t see how nuanced the mechanisms are that stay in place even after emancipation.”

A Different Kind of Plantation Tour

Other plantations in the South host weddings and offer tours of the “big house” by costumed guides, complete with mint juleps on the porch and nary a mention of the brutality that earned the owners their fortunes.

The Whitney is strikingly different, asking visitors to confront the country’s deep-seated effects of racism. It is considered the first and still one of the only museums in the country to focus on slavery. Mitch Landrieu, the former mayor of New Orleans and a top advisor to President Biden, once compared the site’s significance to Auschwitz.

The plantation was started in 1752 by the Haydel family and expanded over the years, growing indigo plants, rice, and, most important, sugar. Sugar was a brutal crop that required constant, hazardous labor, and “for many enslaved people, being sold south to Louisiana was considered a death sentence,” reads the history section on the Whitney’s website. At its peak, the grounds were run by more than 350 enslaved people who produced more than 400,000 pounds of sugar every year. They also tended to the owner’s family, who lived in the Creole-style “big house” mansion, which is flanked by an allée of Spanish moss oaks.

After the Civil War ended, the house fell into disrepair, and its future was uncertain. In 1999, a wealthy local trial lawyer bought the Whitney land. After learning the site’s history and seeing documents that included the names of enslaved people, he felt compelled to invest $8 million of his own money to restore the property and develop it into a museum. He collaborated with artists, historians, preservationists, and researchers in the lead-up to the site’s 2014 opening.

Today, when visitors arrive at the Whitney, they receive a card with the name and story of a formerly enslaved person who’d been interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project in the 1930s. Eerily placed around the site’s chapel are 40 life-size casts of slave children who lived—and, in many cases, died—on the plantation. The grounds also include seven slave cabins, and just outside their doors are massive iron kettles that enslaved people used to boil sugar cane.

Although Snyder has spent years studying historic preservation and interpretation of 19th-century US historical sites tied to the history of enslavement, she was surprised and affected by her first visit to the Whitney.

“The mission of the site is to provide a history of slavery, and so when you go around the grounds and through the buildings, it feels like you are genuinely following these enslaved men, women, and families’ life journeys,” she says. “Unlike many other sites, there is little attention given to the enslavers.”

This spring, Snyder, who has a master’s degree in library and information science from Wayne State University, was looking for an internship and contacted executive director Rogers, who enthusiastically hired her to help finish their store’s archives project.

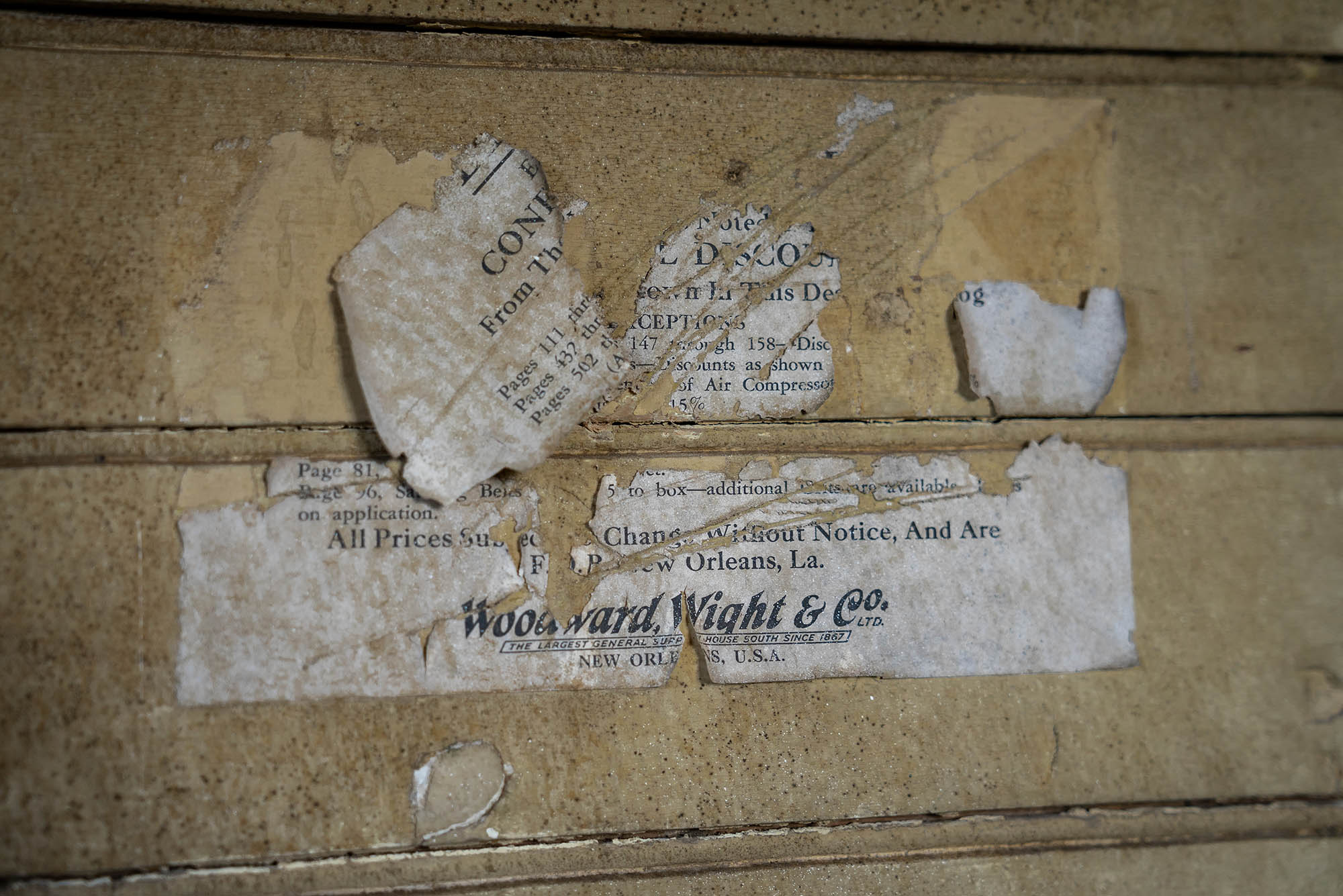

Before the Whitney opened to the public, Rogers had found previously untouched boxes of records in the plantation store. Much of the contents had been damaged and were covered in dirt and dust, but she salvaged hundreds of records spanning 1939 to 1975. In 2015, Rogers began working on this archival research project with help from previous interns and the Historic New Orleans Collection. In 2022, the Whitney received $85,000 from the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, a program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, to aid in the project.

“Everything had already been sorted into major themes, but there was no structure within those themes,” Rogers says. “Mary’s work this summer has helped to cap off a decade-long project. These records tell the story of the plantation in the 20th century, and they will be invaluable to Whitney Plantation as well as future researchers.”

Snyder created a cataloging system within the existing overarching structure. She reorganized and meticulously ordered the records, which had been stacked in boxes or housed in sheets of transparent Mylar. Most important, she inventoried each box and created a metadata system (a structured index), which will be especially helpful to future researchers. Her work is also helping inform the ongoing physical restoration and interpretation of the plantation store, which will one day be open to visitors.

Snyder says those brittle invoices, payroll records, medical bills, and letters revealed a few themes. “They paint a really paternalistic picture of how, while these workers were no longer enslaved, the plantation owners maintained control over their lives through wage-fixing and other means,” she says. “They created a system in which anything that the employee or the laborer needed, the plantation store would source those things, and then determine how much to deduct from their paycheck. A lot of times the laborers didn’t even have cash in hand. And that was to restrict their economic mobility. So my work traced that.”

Many of the store records had been damaged and were covered in dirt and dust, but hundreds were salvaged—and can now be studied. Photos by Sydney Joelle Walker

Rogers says she is unaware of any other Southern plantation doing similar work with their store records, though she has seen some plantation store records in university archives. “On the whole, I think this is a very under-researched area,” she says. “I think that because plantations are so focused on the antebellum era, they may not see the value in preserving these 20th-century records.” She hopes that the analysis of how plantations operated in the 20th century will soon catch up to what we know about their Civil War-era histories.

Snyder says she was honored to work on the Whitney Plantation and chip away at this project. “It is a museum that really does fulfill its mission: it is dedicated to pushing forth a more inclusive narrative,” she says. “It was also eye-opening for me, as someone who usually is in the 19th-century space, to recognize how little we fully understand what happened in 20th century daily life… Preserving and interpreting records and buildings from this period will help us all better understand how the legacy of slavery truly permeates through to today.”

Sybil Haydel Morial (Wheelock’52,’55) was a retired educator and longtime community and civil rights activist in her home city of New Orleans. She died at age 91 on September 4.

In her memoir, Witness to Change: From Jim Crow to Political Empowerment (John F. Blair, 2015), Morial recounts the story of her great-great-grandmother Anna, who was purchased from an auction house by the Whitney Plantation’s original owners, Marcelin and Azelie Haydel. As was the case with many enslaved women, Anna was assaulted by one of the Haydel men, and her son was, therefore, also enslaved.

Eventually, Morial’s family fought their way off the plantation. In her book, she describes how she grew up in New Orleans’ Seventh Ward in a bungalow built “by a freeborn man of color.” Her father was a respected Creole surgeon. Morial attended Xavier College for two years before transferring to BU, where she met Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon. 59) and went on to earn a master’s in education. Her husband, Ernest “Dutch” Morial, was the first Black mayor of New Orleans. They raised five children.

In addition to her long career in education, Morial organized the Louisiana League of Good Government, which has a mission to increase Black voter registration and turnout, and mentored women to become leaders.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.