Should People Be Fined for Sleeping Outside?

As the US Supreme Court hears a historic case, Grants Pass v. Johnson, on criminalizing people sleeping outside, BU social scientists say there are better ways to prevent and end homelessness

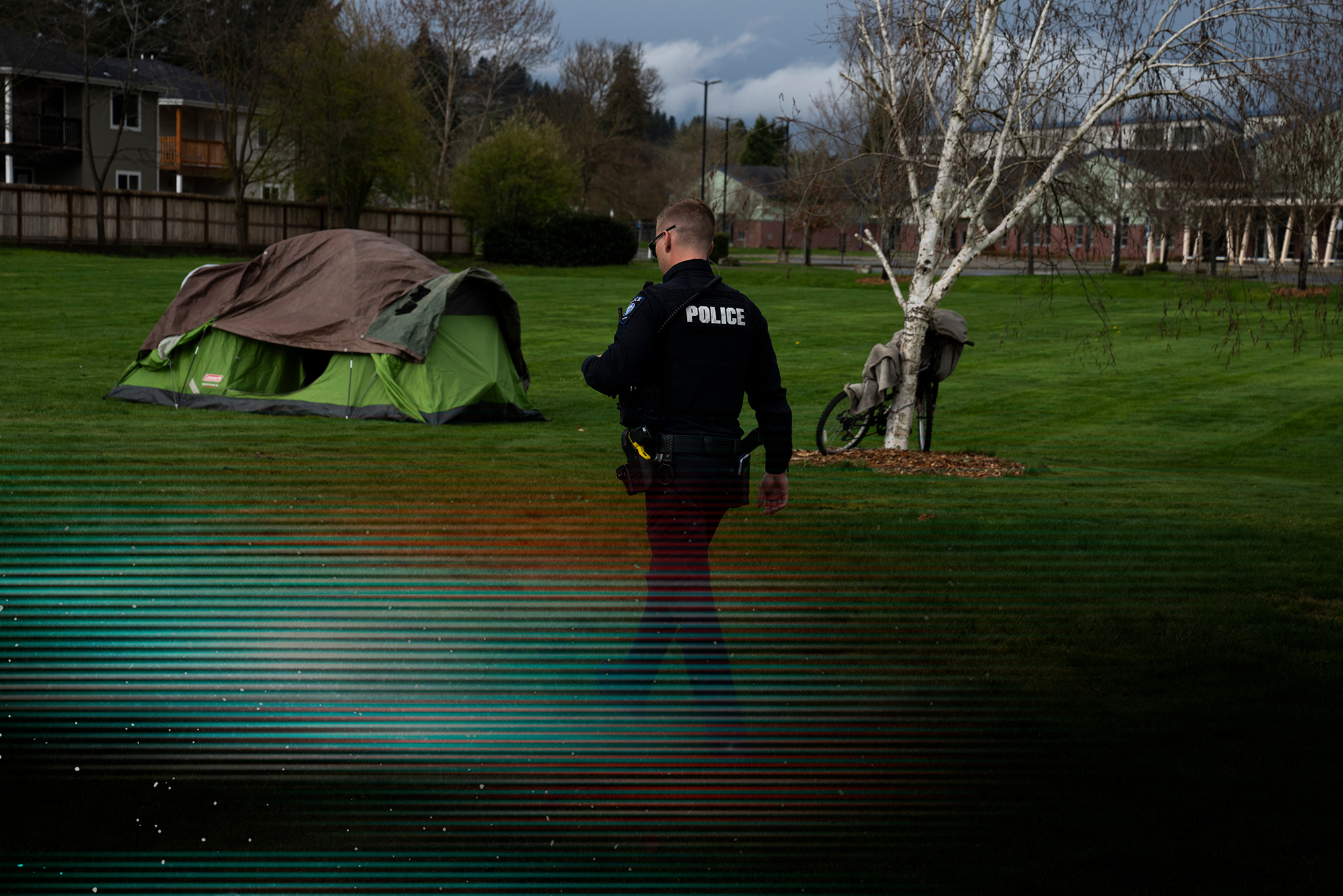

A Grants Pass, Ore., police officer performs a welfare check on a person experiencing homelessness. The US Supreme Court is set to decide if the city’s ordinances clamping down on sleeping outside are unconstitutional. Photo via AP Photo/Jenny Kane

Should cities be allowed to ticket or jail people for sleeping outside, even if they have nowhere else to go? That is the question the US Supreme Court will consider April 22 in City of Grants Pass, Oregon v. Gloria Johnson, when it will decide if local ordinances that punish people for sleeping outside (and for using items like a blanket, pillow, or box to protect themselves from the elements) are considered a “cruel and unusual punishment” under the Eighth Amendment.

As researchers who have focused much of our work on the causes, consequences, and policy solutions to homelessness, we believe they are—and legal experts, including the ACLU and National Homelessness Law Center, make strong cases for this. Moreover, as social scientists who study the most effective responses to preventing and ending homelessness, we also see the case as a time to highlight what works (solutions that focus on housing) and what doesn’t (punitive approaches) to address the nation’s homelessness crisis.

The Grants Pass case comes at a time when the number of people experiencing homelessness in the United States is at an all-time high. After a decade-long period of consistent declines in homelessness between 2007 and 2016, the number of people experiencing homelessness has grown each year since. Between 2022 and 2023 alone, the number of people experiencing homelessness at a given point in time increased by 12 percent—the largest single-year jump on record.

Policymakers at all levels of government are facing increasing pressure to find solutions. In this context, some local officials—including leaders in Grants Pass, Ore.—have attempted to pursue policies that impose fines or jail time for people who bed down on city streets, even when no other alternatives are available. Their goal: deter people experiencing homelessness from staying in the city. Such approaches to homelessness have long been controversial, and the Grants Pass case will decide their fate.

Local leaders argue that they need flexibility to implement laws like the one in question, so they can make progress reducing homelessness in their communities. But policies that criminalize people who are unhoused fail to address homelessness and exacerbate the harm it causes. In a recently submitted amicus brief that we endorse, social scientists gathered evidence showing how the enforcement of anti-homeless laws harms individuals’ health and exacerbates poverty through exposure to environmental hazards, sleep deprivation, fines, incarceration, and lost and destroyed personal belongings. Criminalization measures like the ones enforced by Grants Pass fail to reduce homelessness in public spaces, make no significant impact on public safety, and fail to bridge people to shelters or other service programs that help them exit homelessness.

What works instead? Research we have conducted shows that cities can tackle homelessness through policies that address its root causes. For example, our work shows that as the cost of rent increases in a community, so does the size of its homeless population, and rates of homelessness in a community begin to skyrocket once the median rent in a community exceeds about 32 percent of the median household income. We’ve shown that the impact of rental levels on homelessness persists when looking at different measures of homelessness and rates of homelessness within specific racial groups.

Likewise, we have also documented how rising income inequality is contributing to growth in homelessness via its impact on low-income renters. We’ve also shown that increases across measures of local structural racism—namely inequities across housing, poverty, and criminal justice—contribute to higher rates of homelessness among Black people.

Cities need real solutions. Our colleagues at Boston University have shown that mayors feel accountable to address the issue of homelessness, yet lack the tools to do so. But it’s hard to see how allowing cities to criminalize homelessness will do anything to improve the structural conditions that are the real drivers of homelessness. Instead, communities should pursue solutions that prioritize the one thing that has consistently proven to be effective at addressing homelessness: housing.

More concretely, we know that policies and programs that provide permanent, subsidized housing or shorter-term financial assistance can help people exit homelessness and keep them housed. And we know that, at scale, such strategies can lead to real progress in ending homelessness. Indeed, the US Department of Veterans Affairs has invested heavily in housing-led solutions to homelessness, resulting in a 52 percent decrease in veteran homelessness between 2009 and 2023.

Pursuing policies that have a broader effect on access to quality, affordable housing is also key. For example, our colleagues have demonstrated the critical importance of housing policies—like land use and zoning—to help prevent and end homelessness in the long term. April is National Fair Housing Month, which reminds us that we have tools to prevent race-based housing discrimination, redress histories of uneven urban development, and develop more equitable cities—if we fully enforce our laws and implement our values.

What can you do? First, you can learn more about the Grants Pass case and how to participate in a national week of action. If you have family, friends, or colleagues in Washington, D.C., you could encourage them to attend the Housing Not Handcuffs: Johnson v. Grants Pass Supreme Court Rally at the courthouse on the day of the oral arguments. Finally, regardless of the outcome, you can carry forward knowledge on what works to end homelessness—and what doesn’t—into your own communities.

Molly Richard is a postdoctoral associate at the Boston University Center for Innovation in Social Science. They are a signatory on the Grants Pass v. Johnson amicus brief that 57 social scientists submitted to the Supreme Court. Thomas Byrne is a BU School of Social Work associate professor and an investigator at the Department of Veterans Affairs’ National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans and with the Center for Healthcare Organization & Implementation Research at the VA Bedford Healthcare System.

“Expert Take” is a research-led opinion page that provides commentaries from BU researchers on a variety of issues—local, national, or international—related to their work. Anyone interested in submitting a piece should contact thebrink@bu.edu. The Brink reserves the right to reject or edit submissions. The views expressed are solely those of the author and are not intended to represent the views of Boston University.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.