Secrets of Ancient Egyptian Nile Valley Settlements Found in Forgotten Treasure

Archaeology student’s UROP project delves into 5,000-year-old wood charcoal that had languished at BU for decades

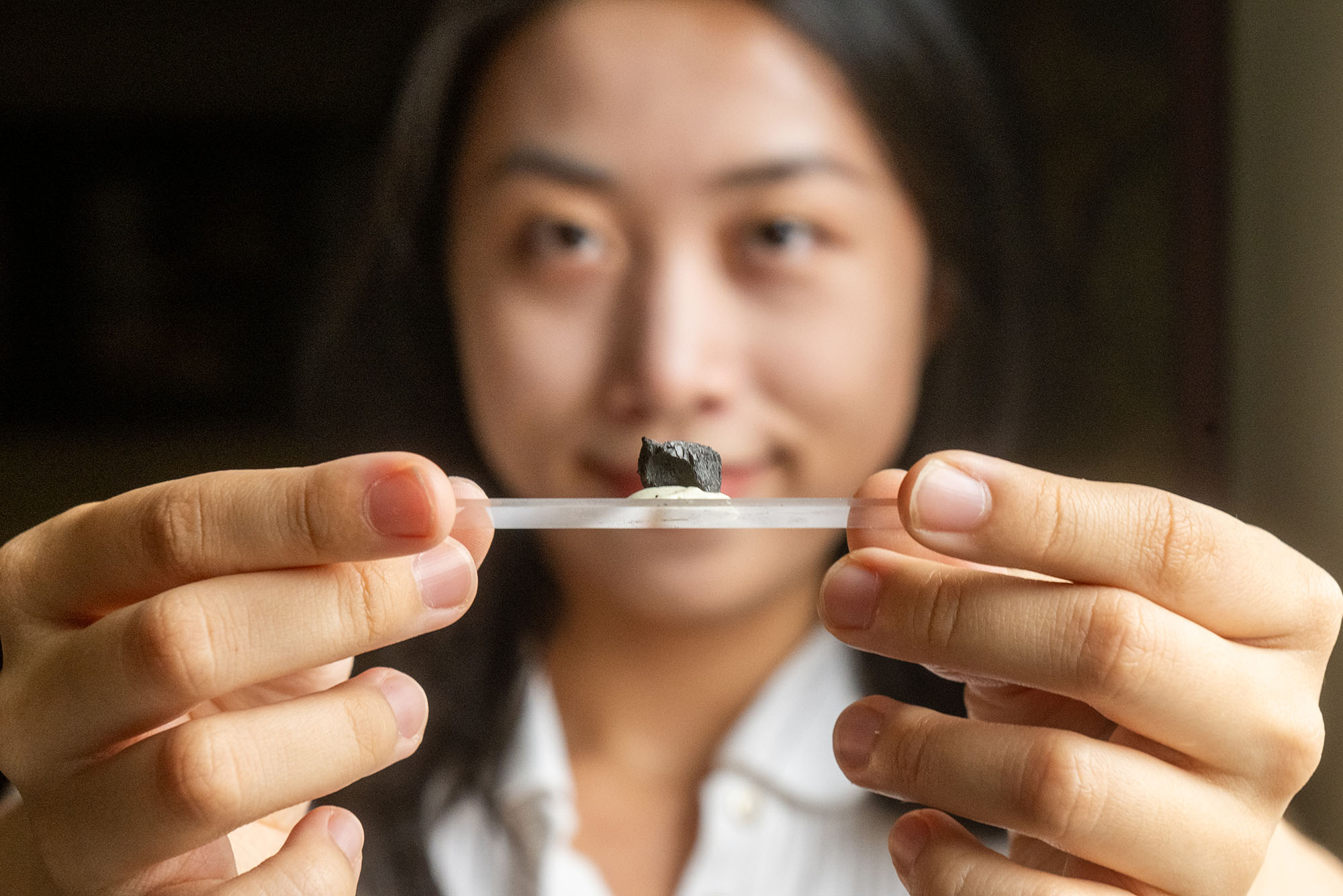

Forget temples and tombs filled with priceless artifacts, BU student researcher Ranran (Angela) Zhang is studying ancient Egyptian history through a more unlikely treasure: wood charcoal burned 5,000 years ago.

Secrets of Ancient Egyptian Nile Valley Settlements Found in Forgotten Treasure

Archaeology student’s UROP project delves into 5,000-year-old wood charcoal that had languished at BU for decades

Ancient Egypt’s riches—its pyramids, temples, and treasures—have drawn archaeologists and explorers to the country for centuries. But one student found Egyptian treasure of a different kind, from a time before the pharaohs, in a long-forgotten cardboard box in a Boston University lab: chunks of wood charcoal burned 5,000 years ago that could unlock secrets of ancient life in less prominent villages and worksites across the vast country.

Ranran (Angela) Zhang (CAS’24), a student researcher in BU’s Environmental Archaeology Lab (EAL), designed an Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program project to analyze the charcoal samples to understand how ancient communities along the Nile—described as “the lifeblood of ancient Egypt”—used the plants and trees around them.

With her research—which she will soon submit to an academic journal—Zhang aimed to identify the types of wood ancient Egyptians burned to answer broader questions about humans’ interaction with their surrounding environment. What kind of wood was available to these people? And how were they collecting it? She was especially interested in figuring out whether the settlements the fragments came from were short- or long-term occupations and what kind of lives the everyday people who called them home had.

Zhang, who is from China, says she likes that this work allowed her to explore the symbiotic relationship between plants and people—specifically people whose stories aren’t written in hieroglyphics on the walls of majestic tombs and temples. “I like that you’re looking at common people and what these common people ate and used,” she says. “And we’re able to reconstruct the daily activities of commoners like me.”

A Dig in the Desert

How did BU come to acquire the wood charcoal? In the late 1980s, Egyptologist Kathryn Bard, a College of Arts & Sciences professor emerita of archaeology and classical studies, traveled to Egypt to do a reconnaissance survey and identified two predynastic (4000–3100 BCE) settlements, Halfiah Gibli and Semaineh.

During multiple visits to the sites—about two kilometers away from one another and near the modern city of Nag Hammadi—Bard made some significant discoveries. She determined the Halfiah Gibli site contained a flint workshop and found agricultural tools; Semaineh had a kiln, with fragments of bread molds, ceramic figurines, and pottery.

Bard’s team also collected wood charcoal samples from the sites for radiocarbon dating, but they sat untouched for years—a common occurrence in archaeology, often due to staffing and the methodical analysis required for each project. When Bard retired in 2022, she gifted them to John Marston, a CAS professor of archaeology and anthropology, who leads the EAL and has done charcoal analysis on other sites.

Marston served as Zhang’s advisor on this project, and says it is so exciting in part because it has been impossible to export archaeological materials from Egypt since the early 1990s; Bard’s wood charcoal samples were taken before these laws were passed. In recent years, the Egyptian government has called for repatriation of its antiquities.

“The traditional focus of Egyptian archaeology has been much less on these boring people, from before the pharaohs, who were doing everyday household activities,” says Marston. “That’s not what Egyptian archaeology is known for. This area has been under-explored compared to other areas of the broader North Africa, Southwest Asia region.”

The caveat Marston makes is that the charcoal samples were not as systematically collected as they would be on a new project today, since they were originally taken for radiocarbon dating. “So, they’re a little bit small and a little bit sparse in comparison to what we would ideally like,” he says. “But it’s still an incredibly rare opportunity.”

Zhang says she came to BU with the hope of studying Egyptology, a dream that looked to be in jeopardy when Bard retired the year she arrived. “Seeing this box feels like destiny to me, because it’s so rare to be able to work directly with Egyptian material,” Zhang says.

Playing Wood Detective

When wood isn’t wholly burned in fireplaces, kilns, and buildings, it becomes inorganic charcoal. Since soil microbes and fungi don’t easily break this material down, Marston explains, it can be found thousands of years later—like in an archaeological dig—and is evidence of direct human interaction with an environment and landscape. It is one of the most commonly found archaeological materials.

“It provides an incredibly powerful lens to understand not only what plants were growing in an environment—woody plants, in particular—but also the ways in which people were choosing to interact with those plant resources,” he says. “We can also study them within their archaeological context to learn much more about how people were using those plants: were they only fuel? Were they used as construction materials or other types of wooden objects? We have the capacity to look at any and all of those with wood charcoal analysis.”

In the lab, archaeologists can study the samples using a stereomicroscope to determine which tree species produced these charcoal remains. The field is known as anthracology. Zhang referenced wood atlases and manuals to help pinpoint the wood’s anatomical structures and other small details. From this meticulous analysis, she identified four different types of trees at the sites: Tamarix (tamarisks), Acacia (acacias), Acacia nilotica (also called Egyptian acacia), and Faidherbia albida (otherwise known as white acacia).

Next, she examined the degree of curvature of each fragment to see if the wood came from small branches or large trunks. She also looked for any hyphae (a long, branching structure of a fungus) to shed light on whether the wood was freshly cut from the tree or already dead and lying on the ground when it was gathered to be burned. Looking at the curvature and hyphae data together, she—along with Marston and PhD student Peter Kováčik (GRS’25), who both collaborated on the project—was able to hypothesize that these people were collecting smaller-diameter branches, as deadwood, from the ground.

“They were not intentionally modifying the landscape, but rather they utilized all the resources around them,” Zhang says. “It also seems that resources were very abundant.” For this reason, she concluded that these were either seasonal or small permanent settlements, maybe outposts of major cities or production centers.

Last, she entered her findings into databases to be used by archaeologists worldwide doing similar work.

Marston says Zhang is his first undergraduate student to do this type of work, which is particularly complicated, uses more sophisticated microscopes, and requires an understanding of cellular anatomy.

Angela applied herself with an incredible tenacity that enabled her to build the skills and the experience needed to be able to identify the archaeological wood charcoal and do a tremendous job in the identifications.

“Angela applied herself with an incredible tenacity that enabled her to build the skills and the experience needed to be able to identify the archaeological wood charcoal and do a tremendous job in the identifications,” he says. “It takes a remarkable level of commitment and achievement for an undergraduate student to do this.”

Next Steps: Using the Past to Inform the Future

Eventually, the research could be expanded to use geographic data, which could “target where people were collecting and can also add to the why, or the choice of location,” says Zhang, who will graduate in May. She’s currently applying to graduate schools in Europe, where she hopes to focus on environmental archaeology and archaeobotany, and work to answer more ecological questions about the past.

“What I hope to do is advocate that archaeological data, together with modern ecological data, can be used to inform future environmental practices, like in managing deforestation,” she says. Zhang hopes her UROP study findings could show other small, modern-day Egyptian villages, for example, ways to not deplete their limited resources.

“A lot of the times, these changes may be small and region-specific, but they’re doable,” she says.

This research was partially funded by BU’s Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.