Cameron Monesmith Got Cancer, Had Two Brain Surgeries, and Now He’s Ready to Graduate

Cameron Monesmith (Questrom’24) was diagnosed with a baseball-sized brain tumor in 2023, his junior year.

Cameron Monesmith Got Cancer, Had Two Brain Surgeries, and Now He’s Ready to Graduate

BU senior, diagnosed with a baseball-sized tumor junior year, never stopped studying, and after brain surgeries and experimental drug treatment his tumor is almost gone. And he’s looking forward.

Update: Cam Monesmith graduated at BU’s 151st Commencement on May 19, 2024. By that time, his tumor had shrunk by over 90 percent, thanks to his treatment. In June, he started a job in investment operations at Fidelity Investments.

“I have really bad news for you. Do you want to know now, or in the morning?”

It was 4 am at Lahey Hospital in Burlington, Mass. Twenty-one-year-old Cameron Monesmith had just been rushed to the emergency department after a two-and-a-half hour MRI. The medical team told him they had “found something”—but they weren’t quite sure what it was yet. When a neurologist finally entered the room, he sat down on the hospital bed and asked Monesmith that question.

Monesmith answered, “Now.”

What came out of the neurologist’s mouth didn’t sound real. “You have a tumor the size of a baseball on your brain stem. We don’t know how to deal with it yet, but you’re going to need brain surgery to remove it.”

For Monesmith (Questrom’24), then a junior at Boston University, this conversation on an early December morning in 2022 began a journey that changed him and his family forever and continues to shape his life. But then, alone in his hospital room, he couldn’t wrap his head around what he had just heard. All he could think was: I need to call my mom.

Spreading numbness

It started with a numbness in his foot.

Cameron—Cam to most people who know him—was vacationing with his family in the Outer Banks of North Carolina right before starting his junior year. At breakfast one morning, he noticed that he couldn’t feel the bottom of his right foot. He chalked it up to stress—he’d missed a flight on his way back from summer study abroad in Dublin, leading to a scramble to book a new flight—and he dismissed it. But as the vacation went on, the numbness spread to his entire foot.

A quick doctor’s appointment yielded nothing wrong with his nervous system. It also yielded a referral to a neurologist in Burlington. But life got in the way—starting Questrom Core classes, getting his car towed, studying for midterms and then finals—and he didn’t make it to the neurologist.

Then sometime that fall, the numbness spread to his whole right side.

The neurologist he saw at his rescheduled appointment December 11 ordered an MRI to check for what he suspected might be multiple sclerosis. Instead, Cam would eventually learn that his diagnosis was a grade one pilocytic astrocytoma, a cancerous, slow-growing tumor that originates from cells that nourish neurons in the brain. Even worse, he was told that his tumor was likely inoperable. And that even if it was operable, fully removing it would cause permanent brain damage. So would radiation.

That morning at Lahey Hospital, he recalls, “around 6 am, a neurosurgeon came in and told me, ‘Hey, so there’s nothing we can do about your tumor. We believe it to be untreatable through surgery. We believe the only option you have is experimental treatment at other hospitals.”

At that point, still reeling from the neurologist’s news, a million thoughts raced through his head: A baseball? In my brain? What does that mean? Am I even myself right now? A supposedly inoperable tumor wasn’t something he could figure out alone. “I remember, my first comment was: ‘Can I call my mom?’”

Monesmith comes from a family of runners. He was eager to resume his running and lifting workouts following his two brain surgeries.

Almost 650 miles away, Kim and Heath Monesmith were asleep in their home in Cleveland, Ohio. Kim’s phone was set to vibrate, so none of their son’s early morning calls woke her. When Cam finally reached her and explained what was happening, his parents packed their bags.

“I remember thinking that I had to get to Boston immediately,” Kim says. “I needed to see Cam, hug him, and tell him it was going to be okay—despite having no idea if it was going to be.”

As unsure as the Monesmiths were, they knew one thing for certain: they weren’t going to accept “inoperable” as a final answer.

“Once we got to Boston, we were on a mission to get him to the best neurosurgeon as quickly as we could,” Kim says.

Of course, that’s not always easy. After two days of frantically “running around,” as Cam puts it, trying to get his brain scans on CDs to send to hospitals for a second opinion, a colleague of his father’s put the family in touch with a renowned San Diego neurosurgeon. When they reached him, he sent them to a neurosurgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital.

That’s when they got their first bit of good news. At Mass General, they were told that while it would be difficult to operate on the tumor because of its location—the surgery would require traveling very carefully through the brain to get all the way down to the brain stem—it wasn’t impossible. They set a date for a craniotomy for two weeks later, on December 27.

But first? Cam had finals coming—and he was determined that an impending brain surgery was not going to stand in the way of taking them.

Seven-hour surgery

By all accounts, Cam has always been a hardworking, eyes-forward kind of guy. He’s an athletic young man from a family of runners—his younger sister, Morgan, is an All-Ivy distance runner at Princeton—and he’s highly committed to his academics.

When he saw the neurologist last December, he was in the middle of studying for Core finals. After emailing his professors with what sounded like the mother of all excuses—essentially writing, “Hi, it turns out I have a brain tumor and need surgery on it; please advise regarding finals.”—he ended up taking two tests as scheduled. He planned to take the other two during the make-up period in January 2023—one month after his scheduled brain surgery.

By the day of his surgery, Cam had been staying with his parents at an Airbnb they’d rented near Copley Square. The family had tried to keep things as normal as possible: going out for dinner most nights and celebrating Christmas. Cam was only a little nervous, he says. His parents, meanwhile, were terrified, but trying to hide it. Not only would this surgery attempt to remove as much of their son’s astrocytoma as possible, it would also reveal what, exactly, they were up against with the tumor.

“We wanted to be strong for him, but it was hard to hide the tears and weight of worry,” Kim says. “It broke my heart to not know the extent of his physical suffering.”

The craniotomy took around seven hours. Surgeons shaved a part of Cam’s head and removed the underlying skull to expose his brain and get to his brain stem. They extracted as much of the tumor as they could and sent a piece for analysis.

The recovery was brutal, Cam says. His left eye was swollen shut. He struggled to speak and answer questions. His vital signs dropped worryingly low before rebounding. His medications—a mix of steroids and painkillers to reduce brain swelling, prevent seizures, and stave off pain that was quickly becoming unbearable—kept him awake. When he did sleep, he would have “horrible, horrible dreams.” Around day four, he began to feel like he was improving—and then he realized he could no longer see on his right periphery.

The scariest moment, however, came after his release. He was still slow to gather his thoughts and speak. He and his parents were walking around the Prudential Center when his dad asked him a question—and Cam couldn’t answer. Only gibberish came out. His parents rushed him back to the hospital, terrified he was having a stroke. A CT scan revealed that his brain was simply overstressed and had experienced a brief cognitive shutdown.

By now, they also had a temporary prognosis for Cam. His tumor was unusual, as pilocytic astrocytomas typically present in early childhood or at a far later stage of life than age 21. The craniotomy had ultimately removed 60 percent of the tumor. While it was unlikely that the astrocytoma would progress to a grade two, three, or four, it was still unclear what the 40 percent still in his brain would do. Would it die out? Grow back slowly, or worse, aggressively? Would medication be able to shrink it? Or was another surgery inevitable? Would radiation, which would likely fry the part of the brain that regulates Cam’s emotions, be their final option?

For now, the doctors said, the general consensus was to wait and see what happened.

Not out of the woods

What would you do if you knew you have a brain tumor biding its time on your brain stem?

After winter break ended, Cam more or less went back to his regularly scheduled programming. He resumed working out—a relief, he says, after a month of taking it easy. He committed to studying for make-up finals, a task in and of itself. For one, reading required extra concentration. It was clear his right peripheral vision wasn’t coming back. Nevertheless, he ended up acing his finance final—despite struggling in the class prior to his surgery. (His professor later emailed him to say how proud she was of him.)

Heading into the spring 2023 semester, classmates assumed he’d take a break.

“Everyone was asking if I was going to take a gap semester, and I was like, ‘No way,’” Cam says. “I knew I could do it; I just needed to really focus and push myself.” Plus, he says, he found himself genuinely enjoying reapplying himself to his studies postsurgery.

“Actually sitting down and learning things felt way more worthwhile than it had before. I think I had a little bit of ‘old-man perspective’—like, death happens, so I need to take the time I have left and use and appreciate it to the best of my ability.”

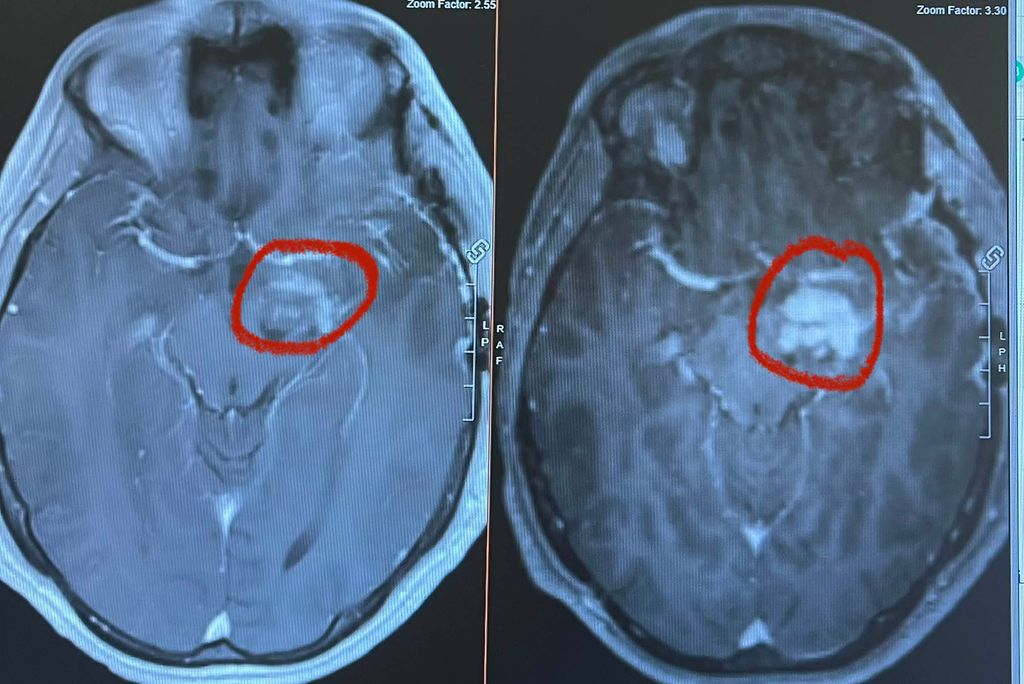

Brain scans taken three weeks apart show the effects of the experimental anticancer drug Mekinist on the remaining portion of Cam Monesmith’s tumor. Photo courtesy of Monesmith

But then, just as things seemed to be getting back to normal, his symptoms returned. About halfway through the semester, he noticed a numbness in his right side while doing his lifting workouts. He started to have trouble answering questions again. Then he began experiencing bouts of intense déjà vu, accompanied by a “roller-coaster” sensation in his stomach—clear symptoms of focal aware seizures. A late-January MRI had turned up normal. The next one did not.

On a Wednesday in late April 2023, while sitting on the fifth floor of Questrom, Cam’s neurosurgeon told him over Zoom that the tumor had grown a cyst that needed to be removed. He would need to have a second craniotomy.

“I thought, oh God, here we go again,” Cam says.

They scheduled the surgery for May 2. This time, he knew what to expect. He amassed electrolyte and protein drinks to help with recovery. He went for a hike with his friends the day before. That was important, he says, not only because he knew he wouldn’t be able to exercise for a while, but because he wanted to spend time with the people who’d stood by him the past few months.

“I began to really appreciate that I had genuine friends who stuck around through everything and made sure I was okay,” he says.

Unfortunately, the second surgery wasn’t as successful as the first. While the medical team was able to “debulk” the cyst, they couldn’t get any more of the tumor. They were also afraid another cyst would just grow back where the other had been. It looked increasingly like radiation might be the next course of treatment.

Unexpected surprise

After the craniotomy, Cam’s doctors put him on Mekinist, an experimental anticancer drug. Largely used to treat certain types of melanoma, in some conditions Mekinist can also prevent tumors from coming back after surgery. It not only worked at the outset for Cam—it kept on working. Almost a month later, the tumor itself had shrunk by 50 percent; three months later, it had shrunk another 30 percent. A little more than one year after Cam’s initial diagnosis, 90 percent of his tumor is gone. It’s miraculous considering his initial prognosis, his mom says.

“Cam’s [first] surgery was not like a typical surgery where the problem is repaired and someone is fixed,” she says. “The worst part of Cam’s diagnosis was how deeply embedded the tumor was in his brain stem—we knew it couldn’t be fully removed without permanently damaging him.” In the months following his initial surgery, “it was difficult not feeling like there was a light at the end of the tunnel.”

Now, the plan is to keep Cam on Mekinist with the hope that the medication will reduce the tumor completely—something the doctors believe could happen.

“It’s a remarkable result even the oncologist can’t believe,” Kim says.

Studying with friends in the GSU. During his recovery, Monesmith says, “I began to really appreciate that I had genuine friends who stuck around through everything,”

After his two surgeries, “Cam seems way more open to using his brain in new ways,” his mom says. Case in point: he taught himself how to play the ukulele.

So who is Cam now, after everything he’s been through? If you ask his academic advisor, a fighter.

“In my 13 years of working in higher education, I have never encountered a more resilient and determined student than Cam,” says Lindsey Itzkowitz (Wheelock’11), associate director of academic success and special programs in Questrom’s Undergraduate Development Center.

Case in point: he overloaded his last semester to catch up on Hub credits. That meant keeping up with readings for five courses—no small task with reduced vision and a recovering brain. But that’s the up-for-the-challenge attitude Itzkowitz came to expect as she helped Cam come up with a plan to get back on track with his courses.

“Most students would have understandably shut down and taken some time off, but Cam did not skip a beat,” she says. “I am so proud of him and beyond impressed by his positive attitude, work ethic, and perseverance. I think we all can learn a lot from how Cam handled this situation.”

If you ask his mom, he’s the best version of himself.

“I think it accelerated his growth as a person,” Kim says. “He journals, he hikes, he reads, he plays a new instrument—he seems way more open to using his brain in new ways.” (Right: Cam taught himself to play the ukulele amidst everything, because, why not?)

If you ask Cam himself, he says he’s just happy to be here. He’s been leaning heavily into his old-man perspective, which manifests as a deep appreciation for pretty much everything.

Monesmith says his experience left him with an “old man perspective” that guides him: “I need to take the time I have left and use and appreciate it to the best of my ability.”

“I’ll go for walks and see a tree and go, wow, that tree grew in a complex way; I like that,” he says, laughing. “That’s the level I’m at these days.”

Otherwise he’s enjoying spending time with his friends before they all go their separate ways. Come May, he’ll graduate with a major in business administration and a minor in computer science. In June, he’ll start a job at Fidelity Investments.

Symptoms-wise, he still experiences the occasional bout of muscle weakness. Or he sometimes bumps into people on Comm Ave—a consequence of his permanent partial vision loss. Driving, too, is harder than it used to be. That remains the biggest letdown, Cam says. But in some ways, it’s also a flex: “If I beat my friend in ping-pong, say, that gives me a total ego boost. I’m like, ‘You just lost to a blind guy—do you even know how to play ping-pong?!’” he jokes.

That, more than anything, best defines Cam Monesmith. Throughout his ordeal, he’s refused to feel sorry for himself. He’s remained determined to push forward no matter the setbacks, to appreciate his opportunities and his loved ones. To set new goals to reach—then reach them.

And, after everything, to celebrate every win. No matter how small.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.