Social Security Clawbacks Are a Year-round Horror, Says BU’s Laurence Kotlikoff in New Book

60 Minutes appearance brings economist’s Social Security Horror Stories to national audience

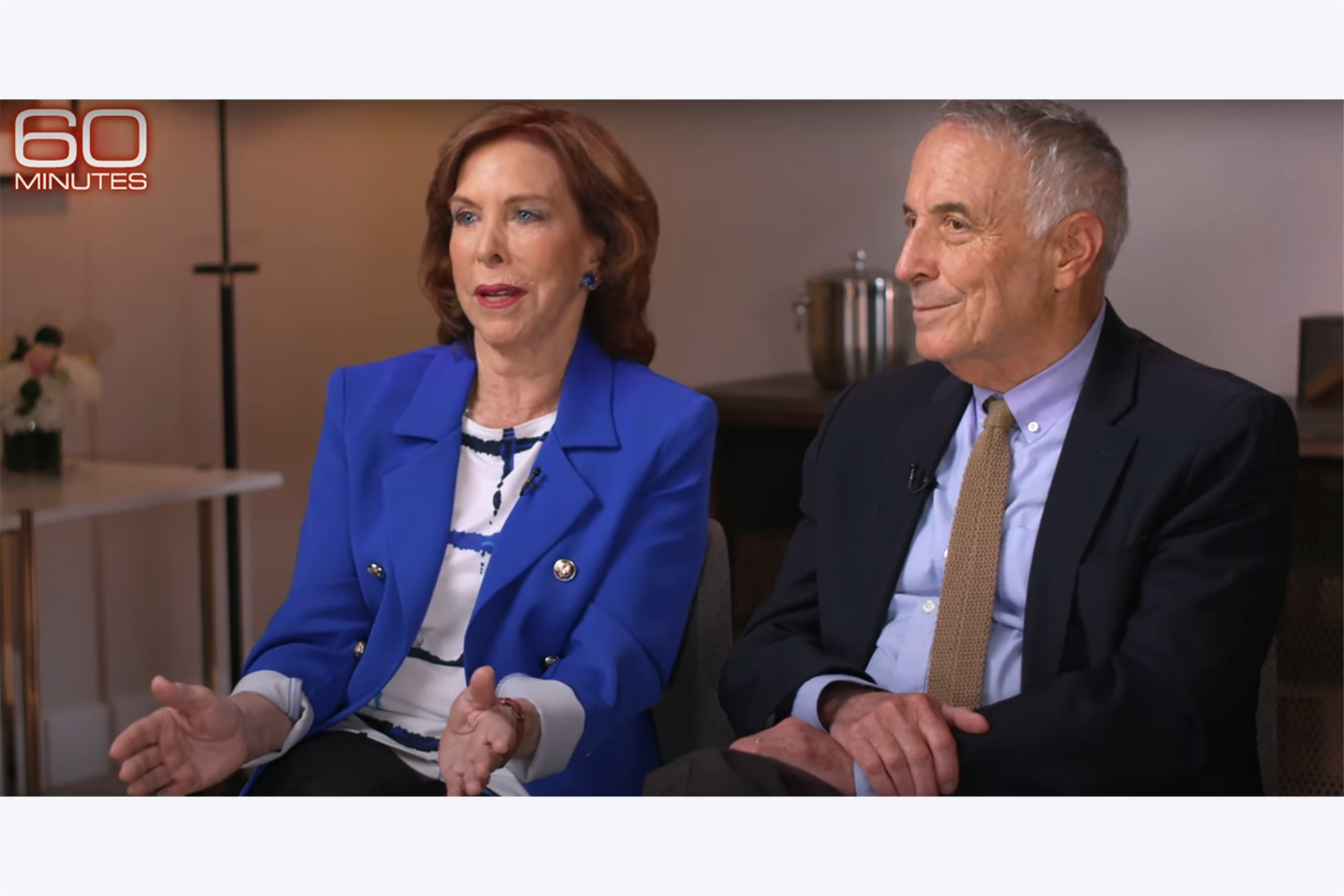

A screenshot of coauthors Terry Savage (left) and Laurence Kotlikoff from Sunday’s 60 Minutes segment.

Social Security Clawbacks Are a Year-round Horror, Says BU’s Laurence Kotlikoff in New Book

60 Minutes appearance brings economist’s Social Security Horror Stories to national audience

They missed Halloween, but these Social Security Horror Stories are too scary for trick-or-treaters anyway.

BU economist Laurence Kotlikoff and syndicated financial columnist Terry Savage launched their new book Sunday night with an appearance on CBS’ 60 Minutes. Despite the title, it’s not about zombie grannies, but rather an exposé of efforts by the Social Security Administration (SSA) to claw back a fortune in supposed overpayments from roughly a million Americans every year. The SSA wants them to pay the money back—often within 30 days—even though Social Security made the errors in the first place.

“It can happen to anyone, and it can take years, even decades, for these unexpected debts to suddenly come to light,” 60 Minutes correspondent Anderson Cooper said during the broadcast. “Few people realize it, but Social Security’s mistakes are your responsibility.”

“It goes against good conscience,” says Kotlikoff, a William Fairfield Warren Professor and College of Arts & Sciences professor of economics. “People are 87, living just off of Social Security, and receive a $30,000 bill. And a couple of weeks later, if they haven’t paid it back, their check is cut. Or eliminated. This is horrific.”

Kotlikoff and coauthor Savage, a syndicated Chicago Tribune financial columnist, are publishing Social Security Horror Stories themselves through Amazon. Kotlikoff had become a regular source of answers for Savage’s column on Social Security and other personal finance topics. Between them, the topic of clawbacks kept coming up, and Kotlikoff suggested they ask readers to send in their stories. When they had 150, they knew it was time to write a book.

The TV segment highlighted several cases, including the Sword family of Chicago, who in 2022 received a letter from the SSA demanding they pay back $51,877 of overpayments—within 30 days.

“They’re saying you should have known that Social Security was giving you too much money,” Cooper said, “even though they didn’t know they were giving you too much money.”

The Merriam-Webster definition of clawback: “the act or an instance of getting back money or benefits previously given out.” In this case, what it means is Social Security has overpaid many thousands of unknowing people over the years, and now, with its back against the wall financially, it’s trying to take it back. More than 900,000 Americans received the dreaded clawback letter in FY 2023, and more than a million others the year before.

Social Security sometimes just doesn’t have the information it needs to make the correct benefit calculations for millions of Americans, Kotlikoff says. As a result, it often overpays, sometimes by thousands and thousands of dollars over decades. Most recipients are unaware of the error—until they get a letter from Social Security telling them that they must now repay the difference.

“For example, if you work in Massachusetts as a teacher, you’re not going to be covered under Social Security, you’re going to get a pension from Massachusetts when you retire,” Kotlikoff says. Normally your Social Security benefits would be reduced in relation to the size of that pension, “but Social Security doesn’t actually get that information about your pension from anyone. The IRS doesn’t send it to them. The school system doesn’t send it to them. So basically they overpay you.

“And they don’t really want to tell people that they don’t know. They don’t want to say to people, ‘Tell us this number so we can cut your benefit,’ because if they do that, people won’t tell them the real number. So they don’t get the number. And they overpay.

They’re saying you should have known that Social Security was giving you too much money, even though they didn’t know they were giving you too much money.

“People aren’t aware that they need to tell them, so they get overpaid for potentially decades, and then they get a bill in the mail. I’ve seen clawback bills as large as $301,000. I’ve seen people clawed back for an extra $175 a month that they received at age 19, and they’re being called back 45 years later, because they graduated high school a month earlier than Social Security had thought.

“It’s producing a horror show,” Kotlikoff says, hence the title of the book.

When 60 Minutes asked the SSA for answers, Cooper said, the agency cited privacy rules in refusing to discuss specific cases, declined an on-camera interview, and issued a brief statement justifying its efforts as required by law. But it also quickly notified all of the people whose horror stories were featured in the broadcast that they won’t have to pay back the money after all. And the agency said it is reviewing its clawback policy.

But why is this happening?

“The system is broken, far beyond what the politicians are revealing,” says Kotlikoff, a retirement planning evangelist and a vigorous critic of Social Security’s vast bureaucracy and looming insolvency. He cites a Social Security trustees report from March, which shows “that the unfunded liability, the obligations to pay benefits that are not covered by projected taxes as well as the trust fund, is now at $65.9 trillion.” Various estimates say Social Security will be insolvent at different times during the 2030s.

The agency has 10,000 claim adjusters, Kotlikoff said on 60 Minutes, and they’re being told, “Collect every penny you can, no matter what.”

If you’ve gotten one of those clawback letters, you can ask for a waiver. “Well, they won’t waive it unless you can prove it was their mistake,” Kotlikoff tells BU Today, “and then you might have to go back 15 years, and have no record whatsoever of your interaction, no way to prove it. And even if you can prove it, they say you also have to show that you’re indigent, that you’re absolutely impoverished.”

The least the SSA could do, Savage told Cooper, is establish a statute of limitations on how much time can pass before they come after you.

What can you do to avoid getting in this situation in the first place?

“If you go to apply for a benefit, if you’re interacting with anybody from Social Security, record the session, Kotlikoff advises. “They will claim you can’t. The law says you can. And take copious notes.

“This is especially true if you’re getting a pension from non-covered employment or if you’re on disability and you have earnings, two cases where callbacks arise a lot,” he says. “And make sure you inform Social Security by certified mail every month about the check you’re getting from your non-covered employment or from your employer.”

Of course the best answer, Kotlikoff says, is to use his Maximize My Social Security software, which was briefly touted in the 60 Minutes segment. Because no matter what you do, there are going to be mistakes in a system this complicated. “The system is incredibly complicated. There’s 12 basic benefits here. There are 2,728 rules in the handbook about those 12 benefits, and then there’s hundreds of thousands of rules about the 2,728 rules.

“You have no chance of understanding it all, and you also have no chance of understanding it if you’re a regular Social Security claims rep. It’s too complicated,” Kotlikoff says. “So half of what people are being told by the folks at Social Security is either wrong or misleading or incomplete. So people are being led to make mistakes routinely by the system. That’s part of the bigger picture.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.