What Juneteenth Means to Me: a Photo Essay

Photo by Richard Levine/Alamy

What Juneteenth Means to Me: a Photo Essay

The BU community’s reflections on the holiday’s significance: “Juneteenth, for me… is equal parts celebration and remembrance”

Editor’s Note: This year, Juneteenth falls on a Sunday, making the federal holiday Monday, June 20, but BU will observe it on Friday, June 17. Memorial Day displaced a 2022 Summer Term I Monday class day, so the University decided to recognize Juneteenth on the previous Friday to ensure all Monday summer course classes meet the required number of hours.

Juneteenth commemorates the events of June 19, 1865, when Union General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Tex., to inform enslaved African Americans that the Civil War had ended and they were free. Granger’s news came two months after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House and more than two years after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

Long celebrated in African American communities—particularly in the South—Juneteenth did not become a federal holiday until 2021, following a national reckoning on race precipitated by the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and other Black Americans as well as nationwide protests against police brutality.

Also known as “Emancipation Day,” “Freedom Day,” and the nation’s “second Independence Day,” Juneteenth means different things to different people. For many, it is a time to gather with family and friends. For others, it’s a time to reflect on the work that remains to be done addressing institutional racism and systemic inequality.

Before this year’s observance of the holiday, BU Today asked members of the Boston University community to share what the holiday means to them.

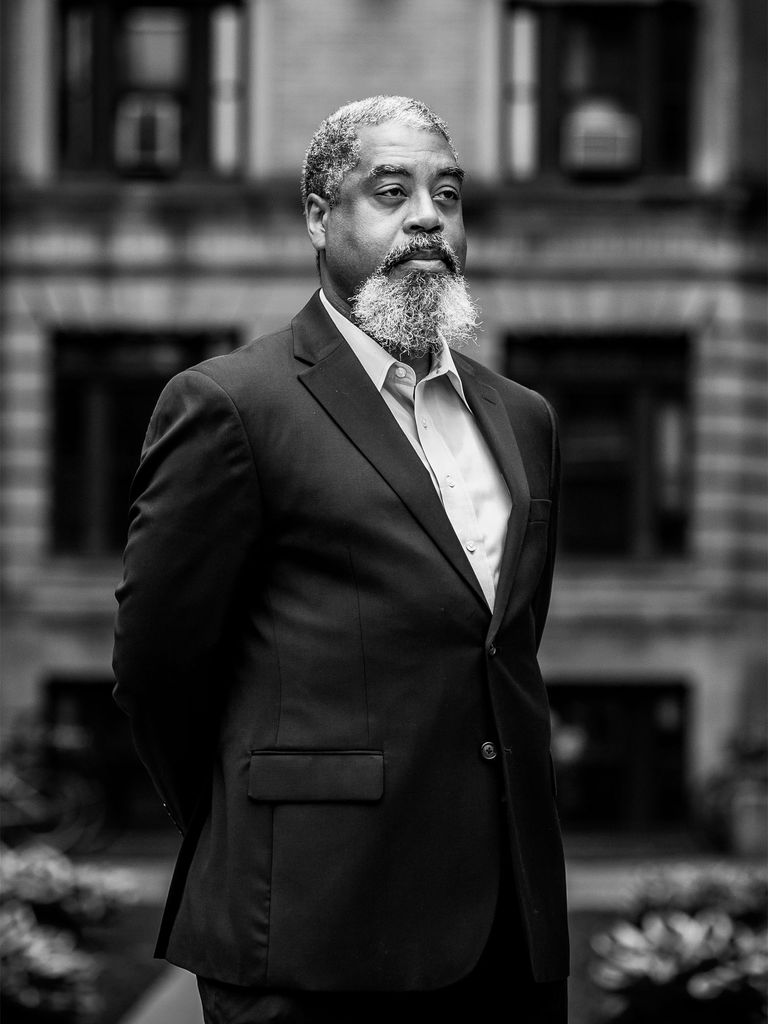

Phillipe CopelandSchool of Social Work Clinical Assistant Professor

In Black Reconstruction in America, W.E.B. Du Bois memorialized the enslavement and emancipation of Africans this way: “The most significant drama in the last thousand years of human history is the transportation of ten million human beings out of the dark beauty of their mother continent in the new-found Eldorado of the West. They descended into Hell; and in the third century they arose from the dead, in the finest effort to achieve democracy for the working millions which this world had ever seen.”

Juneteenth is an opportunity for all freedom-loving people to celebrate this epic drama, to remember its heroes and sheroes, honor their gains, mourn their losses, and learn from both. It is proper that we take a day out of each year to honor our greatest social movement, Abolition. It is proper that we remember the business that remains unfinished from that movement, to contemplate Emancipation as a process, not an event. Juneteenth offers us a Sankofa moment, to go back and get the gifts our Ancestors have left, and use those gifts to become the Ancestors future generations deserve. And even as we face the public and private Hell so many have descended into in recent years, Juneteenth should remind us that Hell can’t have the last word, that each of us can and should rise from the dead, and fight to live fully and freely. Moreover, that we should fight for others as hard as we do for ourselves. Emancipation for all and Happy Juneteenth.

Tomeka Frieson (SPH’23)

My great-grandmother lived to be 103 years old. However, it wasn’t until after her death that I realized that living to 103 meant that she had not just seen the evils of slavery; she was enslaved. And then a sharecropper. And then a housekeeper. Upon diving into my family’s history, I discovered that this was the path traveled by countless ancestors, which began when they were stolen to a new land and has never truly ended.

In the summer of 2020, amidst protests against the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, national conversations brought definitions to the forefront that evoked feelings and identities that I had never before had the language to describe, among them “generational African American” and “Juneteenth.” By definition, I was generational African American, a descendant of enslaved people, and by definition, Juneteenth was a holiday designed to celebrate my heritage.

While Juneteenth has been celebrated throughout the Southern United States for years on end, it hadn’t been something that my family from Alabama celebrated until we had the language to do so. Language is power, and with the power I held from knowing that this holiday was meant for me, I also had the ability to integrate this celebration into my life, and the responsibility—I felt—to continually learn about my heritage.

Juneteenth, for me, then, is equal parts celebration and remembrance—of heroes like my great-grandmother, as well as others who have paved the way before me. I will continue to celebrate this day by diving even deeper into my genealogy, honoring the fruits that my family tree has borne, and documenting stories of my heritage for generations to come. Through my ancestors’ work and sacrifice, I am who I am today. Today, and every day, I honor them.

Angela Onwuachi-WilligSchool of Law Dean and Ryan Roth Gallo & Ernest J. Gallo Professor of Law

Juneteenth commemorates the day when enslaved Black people in Texas were finally informed that through an executive order, President Abraham Lincoln had declared their freedom in the states that seceded from the Union. That day, June 19, 1865, came almost two-and-one-half years after President Lincoln officially signed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. It took another six months before the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which prohibits slavery, was ratified on December 6, 1865. Even after the Thirteenth Amendment became the law of the land, enslavement merely shifted into other forms of servitude and oppression, such as sharecropping and later a brutal system of Jim Crow.

As a child growing up in Houston, Tex., I, like many African Americans, celebrated Juneteenth annually. Each Juneteenth, I think of the poignant speech that former slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass gave to a white audience in Rochester, N.Y., on the 76th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence’s signing in 1857. Through the speech’s title, Douglass posed the question: “What, to the American slave, is the Fourth of July?” And, Douglass powerfully responded, in part, with the answer: “a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery…” Douglass explained that he did not truly feel “included within the pale of this glorious anniversary,” stressing that the holiday only further revealed “the immeasurable distance between” him and his white brethren.

This Juneteenth, 165 years after Douglass challenged his audience to think more deeply about how we have defined independence, we as a nation should reflect on our shared history (and present) of racism and oppression as well as celebrate the tremendous contributions of African Americans to this country. For all of us, not just Blacks, Juneteenth is, in many ways, our true “Independence Day,” because it was the day that the last remaining formally enslaved people—real, live Americans—finally learned that formal slavery could not be legally permitted in our great nation. As a lawyer, I also now appreciate how Juneteenth provides an opportunity for us to reflect deeply upon what true democracy means and what actual freedom and justice for all should look like.

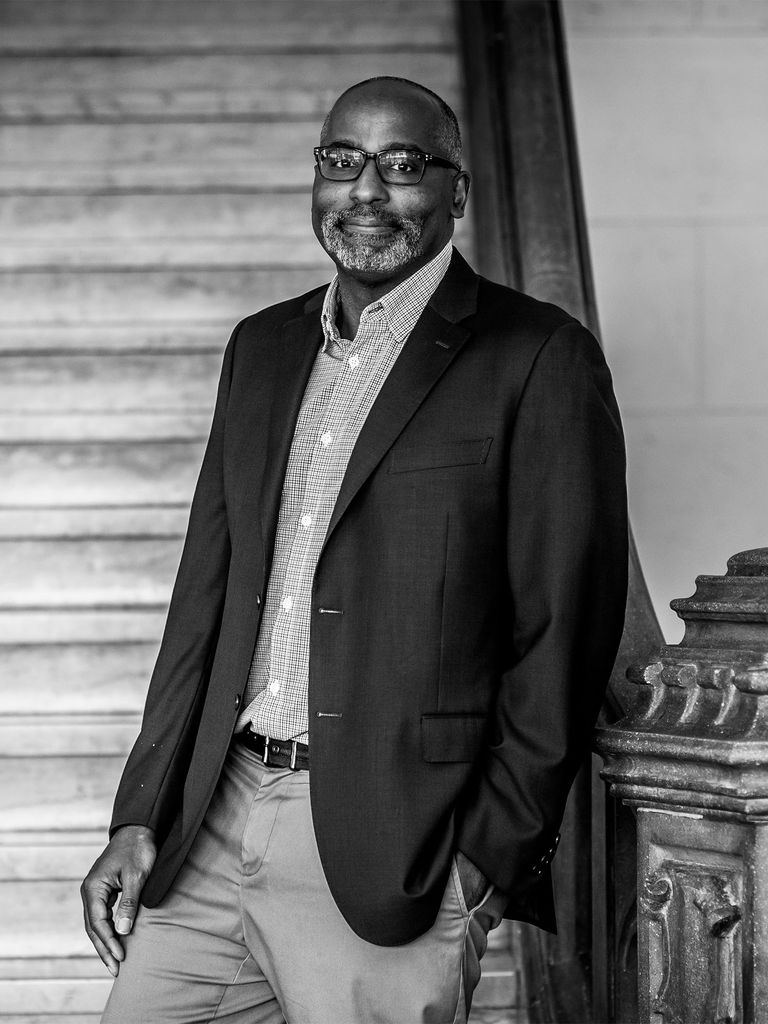

Spencer PistonCollege of Arts & Sciences Associate Professor of Political Science and Assistant Director of Policy, BU Center for Antiracist Research

I prefer to think about Juneteenth as an instance of symbolic politics. While holidays do not directly alter people’s material circumstances, they are important symbols—a critical site of cultural power. This is because national holidays tell stories about the country’s identity, origin, meaning, and purpose. In turn, these stories shape the ideological terrain on which political battles are fought. The debate about Black reparations, for example, revolves around stories we tell about American history, and the extent to which white wealth has been created through the exploitation of Black labor.

So it’s critical that the history is told correctly. I therefore encourage readers to check out a series of wonderful articles published by the African American Intellectual History Society through their journal Black Perspectives.

I will emphasize just one big takeaway that I drew from these essays, especially from the essay by the historian Dr. James Jones III: political victories (and losses) are always incomplete, never permanent. The Emancipation Proclamation was read in January of 1863, and Black slaves in Galveston, Tex., learned about it that same year—but remained slaves. When Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate States Army, surrendered in April of 1865, this too was insufficient to free them. On June 19 of that year—now celebrated as Juneteenth—Union General Gordon Granger entered Galveston, took control, and announced that the slaves there were to be free; but plantation owners still forced the ostensibly free former slaves to work for the rest of the season.

Yet, through continued struggle, the system of chattel slavery did eventually come to an end. The locus of political battle shifted to other arenas, including the question of which stories are told about slavery’s meaning, purpose, and consequences. Today, in some areas of the country (including Texas), it has recently become illegal to discuss at least some aspects of racism in school at all. In other areas, the stories that are told have improved dramatically. I never learned about Juneteenth in elementary school; my 10-year-old daughter knows its history well. The struggle continues.

Harvey YoungDean, College of Fine Arts, CFA Professor of Theater, and CAS Professor of English

As a kid, Juneteenth always seemed to be a secret holiday. My extended family—aunts, uncles, cousins—would gather at a park and barbecue. Games would be played. Music would blare from portable boom boxes. Gladys Knight sang about a midnight train from Georgia as ribs smoked on nearby grills.

It felt like a rehearsal for July 4. However, there were differences. Grocery stores didn’t have Juneteenth sales. Only “urban” radio mentioned the holiday. Surveying the other picnic areas, it seemed like only Black folks knew.

Admittedly, Juneteenth doesn’t recognize a historically significant event. It remembers the occasion in which enslaved African Americans in a Confederate state learned of their emancipation, two years after Abraham Lincoln’s Proclamation. Slavery was over. Almost. The 13th amendment, abolishing slavery, would be ratified six months later.

We celebrate Juneteenth because African American communities everywhere chose the date as a marker, as a starting point, at which Black men, women, and children might begin to have access to the rights and liberties outlined 90 years earlier in the Declaration of Independence.

Juneteenth is also a reminder of the headwinds to social justice. There’s a reason why it took two years for news of freedom to spread.

Embedded within the holiday is a call to work actively in support of equity, access, and inclusion.

Katherine KennedyDirector, Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground

For me, the celebration of the emancipation of slavery of Black people happened twice a year. Once on the eve of January 1 at church and the second on June 19, known as Juneteenth, at a community-wide family-style picnic at Franklin Park.

Growing up in St. Mark Congregational Church in Roxbury, our tradition was to observe Black freedom on New Year’s Eve. The congregation would gather in the sanctuary at 10:30 pm. There would be a service of lessons and hymns until 11:45 pm when the Pastor would call out to the church sexton, stationed under the church clock. The Pastor would say, “Watchman, watchman, what time is it?” Following the watchman’s response, the congregation would sing a hymn. This was done every five minutes until 11:55. The congregation would then form a circle around the sanctuary with candles in their hands. The Pastor would again shout, “Watchman, watchman, what time is it?” The watchman would answer, “It is midnight, Pastor.” The Pastor would light his candle and in turn each person lit the candle of the person next to them. When everyone’s candles were lit, the Pastor offered a prayer for the New Year.

Everyone then blew out their candle and hugged and wished each other a blessed New Year. We would then celebrate in the Fellowship Hall, with refreshments, music, and sometimes even dancing.

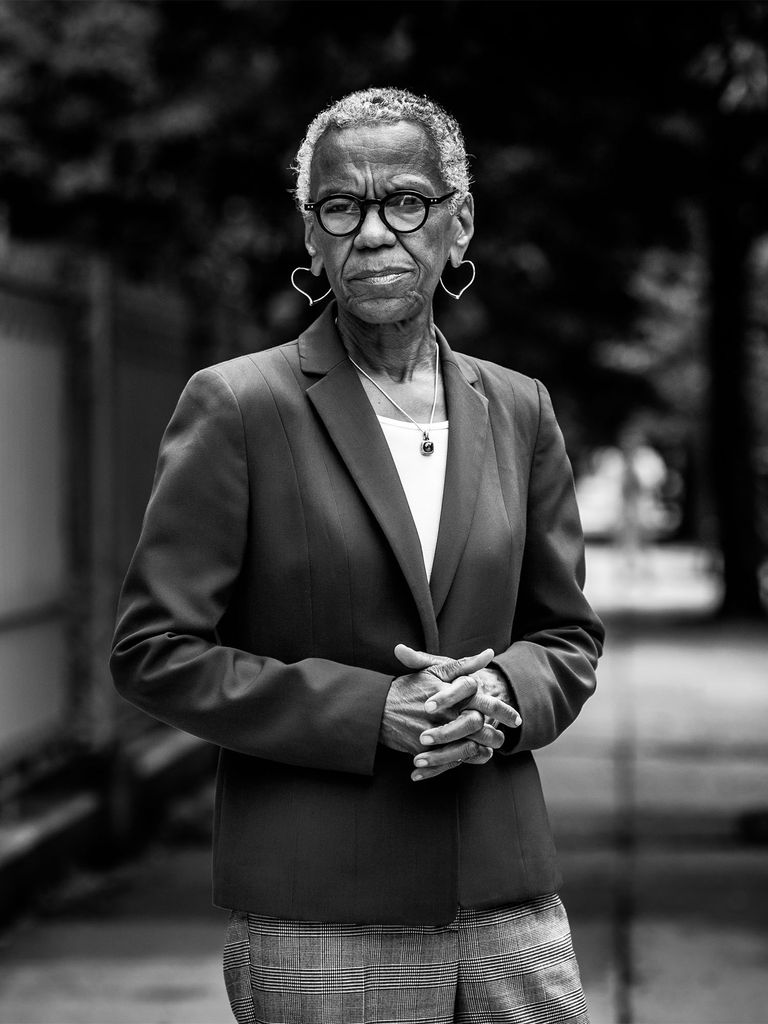

Andrea Taylor (COM’68)Senior Diversity Officer, Boston University

As a great-granddaughter of former slaves, Henry and Margaret Brown, who were uprooted from the Gold Coast—aka Ghana—in the mid-1800s, I believe that President Biden’s declaration of the federal Juneteenth holiday in 2021 was long overdue.

I also agree with Professor Henry Louis Gates that “Juneteenth offers a chance for reflection on the past and consideration for the future.”

Earlier this month, while traveling cross country from Massachusetts to California for the first time since the pandemic, I was pleased to see references and hear about preparations taking place for the upcoming Juneteenth celebrations, now in its second commemorative year as a federal holiday. As many people now know, this long overdue recognition of a pivotal moment in American history originated in Texas in 1865 when news of Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, originally signed in 1862, finally reached the folks in Galveston, Tex..

In the early years following the establishment of Juneteenth, it’s been reported that family reunions were often a cornerstone of Juneteenth celebrations as former slaves went in search of their displaced relatives. Ironically, during my travels earlier this month, in airports coast-to-coast, I witnessed many family reunions as families broke their pandemic isolation and returned to air travel to connect with family members and attend commencement or wedding ceremonies and other family gatherings that had been deferred since early 2020.

The joy and emotion that I witnessed during my recent travels during these moments of reunion at the airports among families of all races was a powerful reminder of our shared humanity. Regardless of race, creed, and other differences, being in community with loved ones is a shared value among all people that transcends our racial, ethnic, political, and other differences.

This year, as individuals and communities seek to reunite as we come out of the pandemic and as you enjoy normal family connections and gatherings, try to imagine the depth of feeling experienced by slaves in the 19th century when they were freed and able to reunite with family and friends separated by slavery and subsequent family disruption in the Jim Crow era.

Karen ColemanUniversity Chaplain for Episcopal Ministry

I was born and raised in Detroit, Mich. The daughter of an academic father and a mother who was the first African American pharmacist at J. L. Hudson’s, a well-known local department store. Detroit Black history runs deep. There were several independent publications that spoke of its rich history, but much of the history was passed down by an oral tradition, stories that my father’s mother told me sitting around her kitchen table. She was a small woman who hailed from South Carolina and who moved north with my grandfather on the promise of a better life. It was my father who taught me about the history of Juneteenth, as it wasn’t in any of my textbooks as a child.

Juneteenth and Emancipation Day—both markers of history—signified freedom for enslaved people in America. What I thought as a child was that Lincoln freed the slaves and one day you were enslaved and the next day you were free. While in the beautiful mind of a child one would wish that was the truth, what I learned from my family’s oral stories was that, unlike the fast rate of speed of news stories today, it was word of mouth carried by those who journeyed trying to find their missing family members. But once former enslaved people heard the word, they mobilized into action and began to set a course for their independent lives.

While stores today rush to carry red velvet cakes, Juneteenth paper plates, and cups to both capitalize and be woke, I still carry the oral tradition of the truth as told to me by those who were told these stories by our ancestors.

Christine McGuireVice President and Associate Provost for Enrollment and Student Administration

Like many native New Englanders, I had no knowledge of Juneteenth until a few years ago. It was an example not only of my ignorance about important days observed by other groups of Americans, but of the bias in our educational system with respect to important milestones in Black history.

I learned Juneteenth recognizes June 19, 1865, the day General Gordon Granger issued General Order No. 3, notifying the enslaved people of Texas they were now free. More broadly, it has come to celebrate Emancipation and the end of chattel slavery in the United States. A reason for celebration to be sure, but it is also an opportunity to confront the real and difficult history of this country. It reminds me to be humble and admit the many blind spots my white privilege affords me. I can’t change history, but I must acknowledge it as the root cause of the pervasive racism that plagues us today.

What we observe and celebrate matters. As a member of Boston University’s Antiracism Working Group, I was proud to help advance the proposal for BU to recognize Juneteenth. Traditionally celebrated as a picnic or BBQ, it is my hope we will find ways to observe the day in community with others, embracing it as an opportunity to learn about and celebrate our individual cultures as well as our shared humanity.

Caleb Brownell (CAS’22)

As an African American, it was surprising not to know anything about Juneteenth until I was in college. Many (if not most) of my peers growing up were Black/POC, but nobody ever acknowledged the holiday—friends, family, schools, jobs—no one.

I discovered the day’s importance following my junior year at BU. I had begun working for Dean Elmore in the Dean of Students office, and I was tasked with assisting in planning the annual Juneteenth Barbecue. At the time, I remember thinking it was just another holiday, another day America pays homage to Black history through celebration, dancing, music, and great food. I saw so many people who couldn’t have seemed happier. I asked, “What are we even celebrating?” first to one student, and then another and another. I got responses like “Black history,” “the day the slaves were freed,” and the more typical “I don’t really know.” I needed to find out more.

When I learned more about where the holiday comes from, I couldn’t help but feel this underlying sense of insincerity. Nobody seemed to care about the 400 years of cultural disturbance, enslavement, and violence that had destroyed the very foundations of where I come from. On top of this, it almost felt like I was saying “thank you” to a terrorist government for finally stopping these injustices against my people. Juneteenth, to me, is a day to reflect and learn, not to celebrate the rights we should have had all along.

So turn up the Beyoncé, grab a plate, and forget about all of it by tomorrow: that’s what it’s all about, right?

Moddie LinenAssistant Director, Judicial Affairs

Juneteenth, although rooted in generational trauma and anguish for many, has helped me come to understand my purpose and meaning of the holiday. The holiday celebrates freedom, but as we witness—time after time—senseless hate and violence against differences in race, ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation still run rampant in our country. The notion of freedom is still elusive for many in our society. Everyday mundane activities, such as the freedom to go to the grocery store, school, and even to church, can still inflict the ultimate price. Indeed, freedom on countless levels is still a work in progress. But as Juneteenth continues to gain national attention, it brings me hope. Not the capitalizing of Black trauma by corporations selling Juneteenth-branded items and having a day off work, but proactive observance. I love the conversations surrounding allyship, bringing diverse communities together in remembrance and celebration, and reflecting on the progression of our culture.

The essence of Juneteenth brings me a sense of pride, responsibility, awareness, and profound gratitude. My ancestors’ and many others’ sacrifices, unimaginable suffering, and triumphs will not be lost. Here is how I plan to bring personal purpose to Juneteenth, and every day: I will endeavor to continue to lead with kindness, stand and speak for those who came before me who could not, and inspire others to achieve their potential. Now, as folks fire up the grill, surrounded by loved ones, playing some feel-good music, keep in mind that this would not be possible without the generations before us, and we must continue their work for the greater good of humanity.

Imara Joroff (LAW’24)President, BU Law Student Government Association

I was born in Vermont to a white mother. She raised me in Hawaii with my white dad and white older sister. From kindergarten to my senior year of high school, I was one of two Black students enrolled at my school across all grades. I then attended a predominantly white liberal arts college in upstate New York. There I met my two best friends: both are white.

I moved to Utah after graduating college in 2019. There, I met two additional best friends: both are Black. I also started to question my place in American society. I grew up with a privileged view of America. I was not taught lessons about driving while Black or shopping while Black. Any discussion of Black history and Black culture was simply a component of my education about American history and American culture. These conversations had nothing to do with preparing me to exist as a Black woman in America.

The first time I heard of and attended a Juneteenth celebration was in the summer of 2020. Unsurprisingly, this was the first time I was around a large number of Black people. Considering both my perceptions and how Black individuals actually treated me throughout my life, this was also the first time I felt welcomed by the Black community.

Juneteenth marked a shift in my identity, my place in society, and the way I interact with others. Sitting in Washington Square Park in Salt Lake City, I was surrounded by Black joy. However, weeks before, the park had been surrounded by the armed National Guard amid Black Lives Matter protests. The difference between these two situations was palpable. It may sound clichéd, but attending that Juneteenth celebration made me feel a part of something bigger than myself.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.