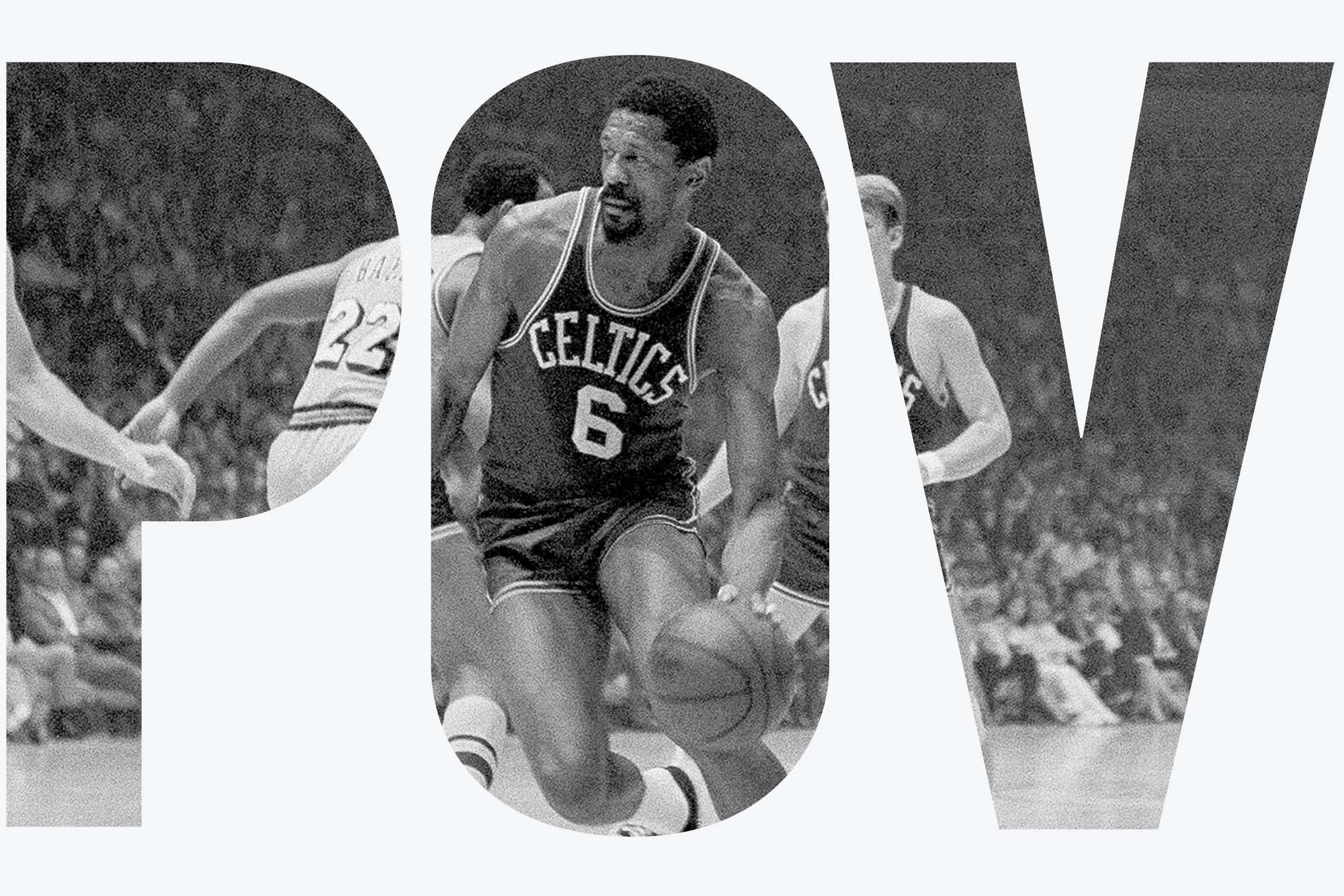

POV: Remembering Boston Celtics Legend Bill Russell (Hon.’02)

File photo by Harold P. Matosian/AP Photo

POV: Remembering Boston Celtics Legend Bill Russell (Hon.’02)

Hall of Famer was “hands down, the greatest athletic figure” to ever grace New England, says biographer Tom Whalen

In an interview I had with former Boston Celtics great Tommy Heinsohn several years back, he shared with me his frustration over the fact that Red Sox Hall of Famer Ted Williams had a “f—–g” traffic tunnel named after him in the heart of the city. He felt the honor was undeserving, because “The Splendid Splinter,” a .344 lifetime batting average notwithstanding, had never brought our quaint little “Hub of the Universe” a single world championship, whereas his former longtime teammate and friend, Bill Russell (Hon.’02), had delivered an eye-popping 11 in 13 NBA seasons, including 8 in a row from 1959 to 1966.

Sorry, Tom Brady. Nice try, David Ortiz (Hon.’17). Step aside, Bobby Orr. But Heinsohn had a point. “The Eagle with a Beard,” as one awestruck opponent once described Russell, is hands down the greatest athletic figure to ever grace the shores of our rocky New England coastline. Russell passed away over the weekend at age 88 and leaves behind a sterling legacy of accomplishments that is likely never to be equaled. A late-blooming, board-crashing center out of Oakland, Calif., by way of the Jim Crow South, he led his University of San Francisco team to two consecutive NCAA titles in college and captained the US Olympic men’s basketball squad to a gold medal–winning performance at the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne, Australia. He also earned 5 league MVP awards in the pros and 12 All-Star appearances. In his memorable on-court battles with fellow pivotman Wilt Chamberlain—the only player in NBA history to score 100 points in a game—he more than held his own. His teams held a commanding 29-20 edge over Chamberlain’s in 49 postseason contests, not to mention a perfect 4-0 mark in Game 7 situations.

“His defensive presence altered the basic flow of the game,” author and media commentator Jeff Greenfield observed. “All of the traditional scoring methods—the lob pass to the big center, the penetration of a guard posting a smaller opponent, the back-door play—were subject to instant nullification by the presence of Russell.” This was because of Russell’s shot-blocking prowess and Svengali-like ability to get inside the heads of opposing players. For sure, mind games were a signature staple in Russell’s defensive arsenal. “Look, I can block shots,” he confided to Jeremiah Tax of Sports Illustrated. “But if I tried to block all the shots my man takes, I’d be dead. The thing I got to do is make my man think I’m gonna block every shot he takes. How can I do it? OK, here. Say I block a shot on you. The next time you’re gonna shoot, I know I can’t block it, but I act exactly the same way as before. I make exactly the same moves. I’m confident. I’m not thinking anymore, but I got you thinking. You can’t think and shoot—nobody can. You’re thinking, will he block this one or won’t he? I don’t even have to block it. You’ll miss.”

Tom Hawkins of the Los Angeles Lakers coined the phrase “Russell-phobia” to describe the unique phenomena. He recalled witnessing players on several occasions breaking toward the hoop for uncontested layups before suddenly freezing up in panic. They would invariably look over their shoulder for Russell to swoop in and swat the ball away. “It’s a thing that happens to people when they play the Celtics,” he said.

Russell was not without his individual quirks. An inveterate practical joker with an ear-piercing laugh likened to that of a giraffe, he could be found nervously vomiting in the locker room before every game as his teammates solemnly stood at attention for the playing of the national anthem. As teammate John Havlicek once told a writer, “It’s a welcome sound, too, because it means he’s keyed up for the game and around the locker room we grin and say, ‘Man, we’re going to be alright tonight.’”

These idiosyncrasies aside, Russell was an intensely serious man who did not suffer fools gladly, often coming off as cold and aloof to outsiders. He routinely refused to sign fan autographs and rankled sports traditionalists by claiming he was no role model for anyone’s children except his own. But he reserved his most trenchant comments on how people of color like himself were traditionally discriminated against by ingrained societal structures of racism and inequality. “Here’s the way I look at it,” he said. “A lot of places I go now I’m acceptable because—well, look, I play golf. I don’t belong to a country club, but I play a lot of them as a guest. As Bill Russell of the Celtics, I’m acceptable. If I tried to join as Bill Russell, citizen, I’d have no chance. I’d have to be awful foolish to believe in what is fondly known as ‘The American Dream.’”

Such frank statements earned Russell pariah status in many corners of the country, especially in the Boston area, which had a well-deserved reputation for being a seething cauldron of racial intolerance in the late 20th century. Russell, in fact, had his suburban home broken into while he was away one weekend and found, upon his return, the N-word spray-painted on his walls and his bed defecated in. Nevertheless, this outrageously disgraceful act of terror did not deter him from being an early proponent of desegregated public schools in Boston or engaging in national civil rights activities his entire life. “A man must do what he thinks is right,” he said.

William Felton Russell always did.

Thomas J. Whalen is a College of General Studies associate professor of social sciences; he has written several books, among them Dynasty’s End: Bill Russell and the 1968-69 World Champion Boston Celtics. He is currently at work on a book tentatively titled Clash of the Titans: Larry Bird, Magic Johnson and the 1984 NBA Finals That Transformed Basketball, scheduled to be published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2024. Whalen first wrote about the Celtics for his high school newspaper when he scored a Boston Garden locker room interview with Larry Bird (Hon.’09) during his rookie season. He can be reached at tjw64@bu.edu.

“POV” is an opinion page that provides timely commentaries from students, faculty, and staff on a variety of issues: on-campus, local, state, national, or international. Anyone interested in submitting a piece, which should be about 700 words long, should contact John O’Rourke at orourkej@bu.edu. BU Today reserves the right to reject or edit submissions. The views expressed are solely those of the author and are not intended to represent the views of Boston University.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.