POV: Why We Can’t Rely on Abortion Pills to Offset Closure of Abortion Clinics

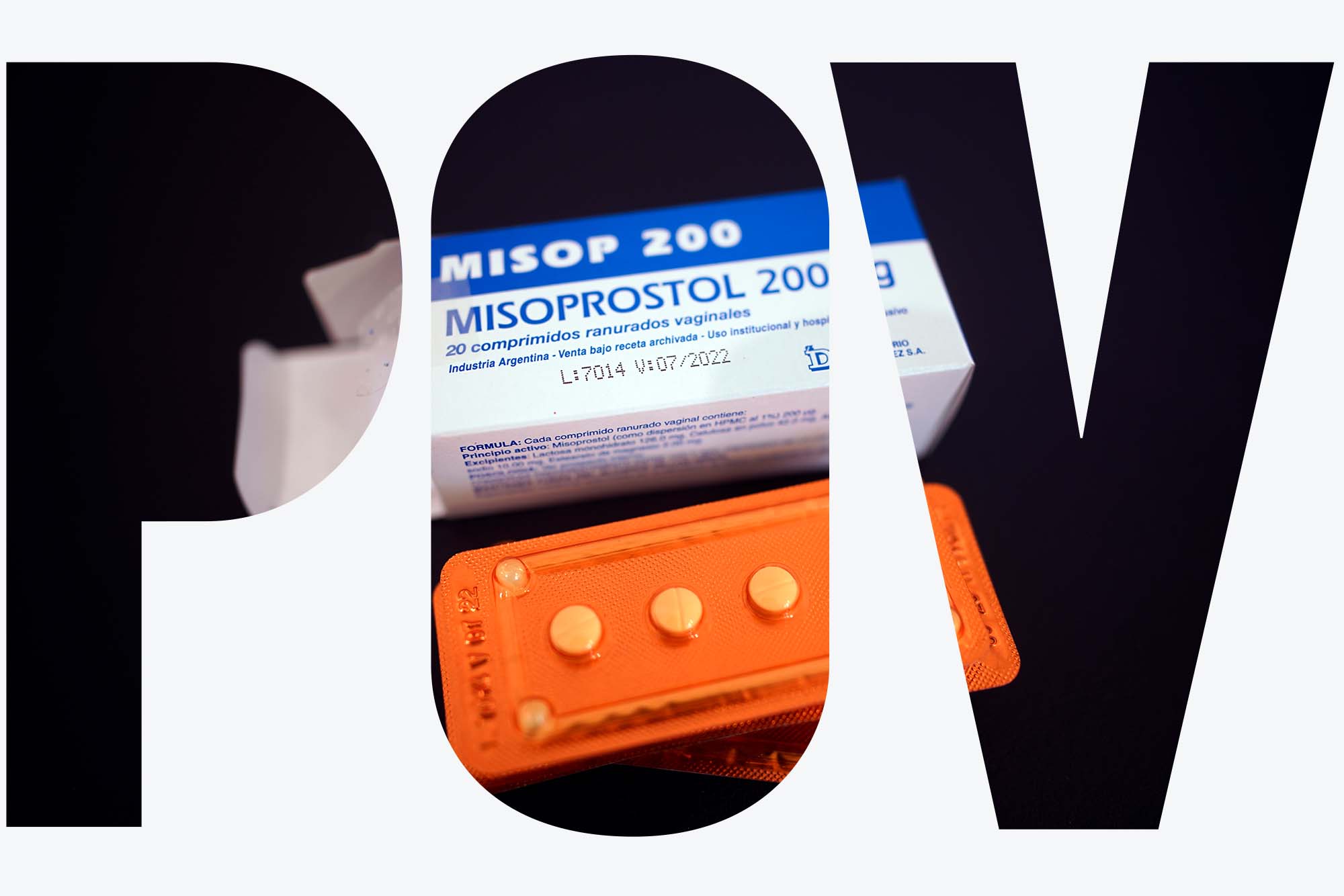

Photo by Victor R. Caivano/AP Photo

POV: Why We Can’t Rely on Abortion Pills to Offset Closure of Abortion Clinics

Medication is not a viable option for many, for a variety of factors

The consequences of overturning Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey have been swift and drastic as clinics across the country cancel appointments, halt operations, or close outright. Abortion is now illegal in Alabama, Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and South Dakota, and earlier this month, Jackson Women’s Health Organization—Mississippi’s only abortion clinic—closed its doors. As similar clinics close, millions of reproductive-age people will lose access to abortion care, effectively banning abortion extralegally. Even more states are likely to enforce pre-Roe bans—laws that were never repealed, but made unconstitutional via Roe v. Wade—or extreme time restraints as to when in the gestational process a person can access abortion. States like Ohio and Texas, for example, have draconian six-week abortion bans in effect.

Many have hailed abortion pills as a solution to the closure of clinics and the enforcement of restrictions that Planned Parenthood v. Casey successfully warded off. While abortion pills are a wonderful option for many people seeking an abortion, they cannot solve every problem that arises with the death of Roe v Wade. Here’s why:

1) Abortion pills fall under the auspices of abortion bans.

States that have banned abortion have not just banned the operation; they have banned the prescription of medicine. Doctors cannot prescribe the pills for medical abortion in states where abortion is outlawed, meaning if someone in such a state wanted to have a medication abortion, they would have to travel out of state to seek care. This is an onerous burden, a ticking-clock situation in which one has to arrange childcare (59 percent of abortions in 2014 were obtained by patients who had had at least one birth), raise funds, arrange transportation, take time off work, and numerous other tasks that are all undue burdens to accessing safe, FDA-approved medications. What’s more, if authorities know that someone has traveled out of state to access an abortion, it is possible that both the person receiving the care and the doctor performing it could be charged and extradited by the state where the care was performed. Thankfully, some states, like Massachusetts, have set in place orders and laws that protect abortion seekers and providers by refusing to extradite them. As previously stated, however, not everyone lives near such a state or could travel to one.

2) The time frame during which one can have an abortion by medication is limited.

Medical abortion comprises taking two medications—mifepristone and misoprostol—in a specific manner. First the patient swallows the mifepristone; 24 hours later, the patient places four dissolving misoprostol tablets under their tongue for 30 minutes, repeating the process three hours later with two more tablets of misoprostol. If no bleeding has occurred, the patient continues the process of placing two misoprostol tablets under their tongue every three hours until bleeding commences.

The time frame during which one can achieve a medication abortion—10 weeks—is narrow. For context on just how limiting this is, if a person finds out they’re pregnant one day after their missed period, they are four weeks and one day pregnant. If a person has a less predictable menstrual cycle (as many people do), then they may not find out they’re pregnant until week five or six. By week six, in four states (Ohio, Texas, Tennessee, and South Carolina), abortion is now illegal.

Accessing routine care at facilities like a dentist or a primary care physician’s office often requires a wait, let alone access to abortion providers. Abortion clinics and reproductive healthcare centers are already stretched thin because there simply are not enough of them since TRAP laws (targeted regulation of abortion providers) shuttered many clinics before Roe fell. If you don’t know you’re pregnant until week six or seven, and then can’t get in to see a provider for another month, you can no longer have a medication abortion.

3) The legality of telemedicine and mail-order meds is murky.

Perhaps the only benefit of COVID has been the explosion of telemedicine, which has consequently been heralded as a way for abortion seekers to access care in a pinch. Beyond the hurdles of accessing care in a timely manner, and without traveling hundreds of miles, the legality of telemedicine and mailed abortion pills remains unclear.

Unfortunately, according to the Guttmacher Institute, “19 states require the clinician providing a medication abortion to be physically present when the medication is administered, thereby prohibiting the use of telemedicine to prescribe medication for abortion.” Another possibility, medications by mail, remains similarly ambiguous. Undoubtedly, abortion-hostile states will continue to legislate against the use of telemedicine and mail-order medications without Roe’s precedent to prohibit such actions.

It is crucial to know that the unknown is just as much of a hurdle for abortion-seekers as explicit restrictions are: now that abortion isn’t explicitly protected by Roe v. Wade, the prevailing question is: what exactly is legal, and where?

4) Medication abortions account for only 54 percent of all abortions performed in the United States. The other 46 percent of people seeking abortions still deserve access to such care and to safe procedures.

To say that people will die from these restrictions is not being dramatic or inflammatory; it is being accurate. When backed into a corner, when medication abortion fails to be a viable option, people will resort to extreme measures to terminate a pregnancy. TikToks advocating the use of pennyroyal tea to induce abortion, for example, have begun circulating, despite the potential dangers of using the herb.

Access to abortion should not be defined by the arbitrary luck of living in a state that protects abortion care; abortion must be a constitutional right.

Jena DiMaggio (GRS’24) is a PhD student and a teaching fellow in the College of Arts & Sciences Writing Program; their research focuses on abortion in American literature and media. They can be reached at jenald@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.