Is YouTube’s Crackdown on Vaccine Misinformation Going to Be Effective?

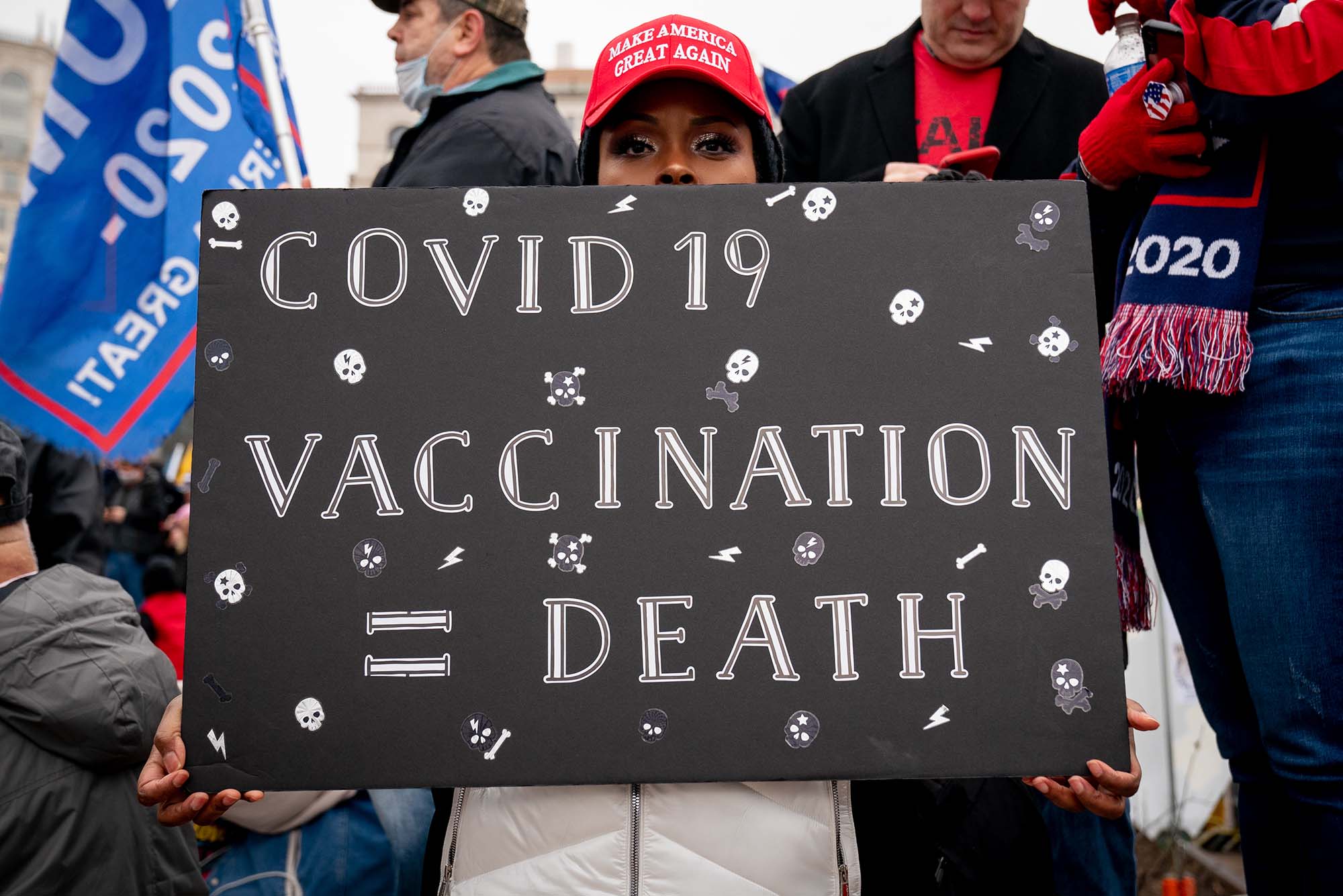

In this January 5, 2021 photo, a protestor holds up an anti-vaccine sign at Freedom Plaza in Washington, D.C. Photo by Erin Scott/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Is YouTube’s Crackdown on Vaccine Misinformation Going to Be Effective?

Social media experts discuss YouTube’s new policy and whether it could backfire

Just as soon as the COVID-19 global pandemic spread like wildfire in early 2020, so did misinformation about how the virus spreads, who’s most susceptible, and more. In response, YouTube updated its community guidelines to prohibit content creators from publishing videos containing COVID-19 misinformation. Now, the social media titan is once again revamping its community guidelines, this time taking aim at content creators trying to push anti-vaccine propaganda.

Last week, YouTube announced it will no longer allow content containing misinformation about any vaccines that are approved and confirmed to be safe and effective by health authorities. The new guidelines include some notable exceptions, allowing for publishers to post “content about vaccine policies, new vaccine trials, and historical vaccine successes or failures” and “personal testimonies relating to vaccines.”

The Brink reached out to two Boston University experts in cybersecurity and online communities to ask what YouTube’s decision to censor vaccine misinformation means, and whether it could backfire. Gianluca Stringhini, a BU College of Engineering assistant professor of computer and electrical engineering and a research fellow at BU’s Rafik B. Hariri Institute for Computing and Computational Science & Engineering, researches the spread of malicious activity on the internet. Nina Cesare, a postdoctoral associate at the BU School of Public Health, uses machine learning to study digital data and how it impacts society.

Q&A

With Gianluca Stringhini and Nina Cesare

The Brink: Vaccine misinformation has been spreading online for the better part of 2021. Why is YouTube implementing this policy now?

Nina Cesare: I suspect this is a reaction to the recent COVID-19 surge attributable to the Delta variant. Projections indicate that viral spread is much more likely among the unvaccinated portion of the population, and that unvaccinated people are much more likely to experience severe and possibly fatal symptoms that require hospitalization. Despite seeing a promising start to vaccine distribution efforts, we’re [still] seeing a dangerous lag in vaccination [rates overall]. We’re past the time to make steps toward combating misinformation.

The Brink: What do you think about YouTube’s new guidelines banning vaccine misinformation?

Gianluca Stringhini: I think that this policy is going in the right direction. There is a fine line to be walked between dangerous misinformation and free speech, and I think that a policy allowing [open] debate about public health measures like vaccine mandates—but not the spread of unfounded health claims—is reasonable.

Cesare: I support efforts to identify and block the spread of vaccine misinformation on social media. If we can take steps toward ensuring [online] posts only spread verified information, it is possible that collective vaccine skepticism will drop.

The Brink: Do you think YouTube’s policy will have a significant impact on vaccine skepticism?

Stringhini: With YouTube being by far the [top] platform for [sharing] video content, a significant reduction in health misinformation on the platform would definitely have an impact on how many users are exposed to it.

At the same time, having one [major] platform crack down on misinformation creates a space for alternative [content-hosting] platforms to flourish. I’m thinking, for example, of BitChute, an alternative [video-hosting] platform where conspiracy theorists have been gathering. While the platform itself has fewer users, [links to its] content can still be shared on mainstream social media [channels] like Facebook and Twitter, allowing a large number of users to see it.

Cesare: I hope this shift will help reduce belief in vaccine misinformation, but I wonder if misinformation will be shared through other platforms. We witnessed a migration toward alternative social media platforms, such as Parler, when Facebook began to flag election-related misinformation. We may see a similar event with this policy shift.

For [people who are] skeptical of [the COVID-19 vaccines’] safety and efficacy, [their] distrust [of vaccines] may be deeply rooted in an array of broader issues…. Identifying the root of this skepticism may be more complex. For these individuals, ensuring they digest accurate facts may not be an effective pathway forward. Building trust in medical institutions may help resolve vaccine skepticism.

The Brink: How does such a large social platform like YouTube ensure that all vaccine-related misinformation is blocked?

Stringhini: This is the tricky part. Unlike text, where we have fairly robust techniques to identify false claims using natural language processing, doing the same thing with videos is much more challenging. Analyzing a video stream requires image processing as well as audio processing, and these techniques are not as well refined and are also much more computationally intensive than text processing. A mechanism that only looks at the title of a video and perhaps at its description would not be as effective, since the video content may actually contain something different than what is advertised.

Cesare: Algorithmic identification of misinformation—especially misinformation transmitted through audio and video—is a computational challenge. Users are clever, and may find ways to bypass feature identification.

Adapted from a post originally published by BU’s Rafik B. Hariri Institute for Computing and Computational Science & Engineering.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.