How Parkinson’s Disease Changes Speech Over Time

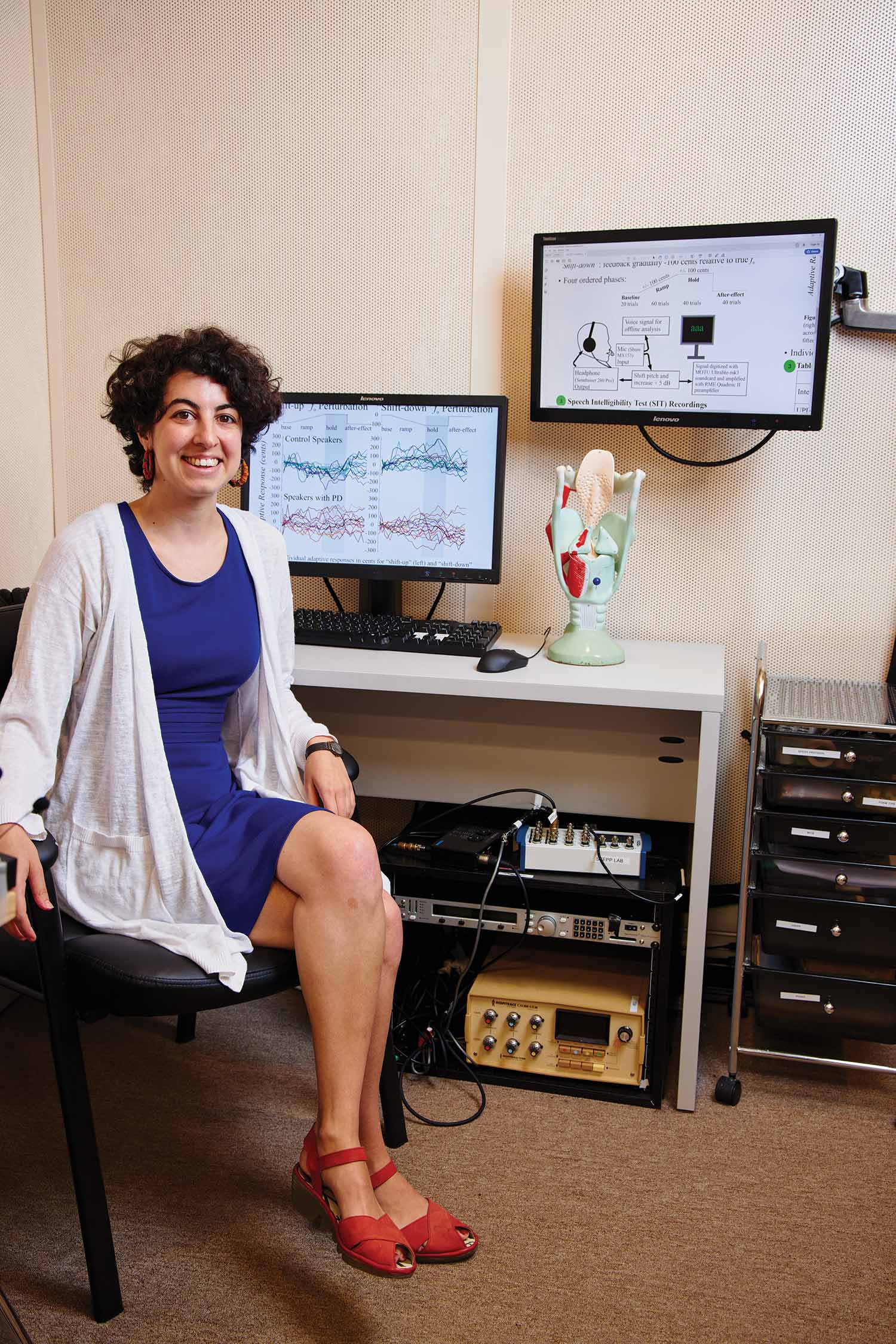

Defne Abur’s NIH grant will help her study the causes of hypokinetic dysarthria in people with Parkinson’s disease. Photo by Dave Green

How Parkinson’s Disease Changes Speech Over Time

BU doctoral student Defne Abur won an NIH grant to study speech disorders in people with Parkinson’s

Around 90 percent of people with Parkinson’s disease also have a motor speech disorder called hypokinetic dysarthria. They become quieter, more monotone, and their vowels and consonants get rough around the edges. But, says Defne Abur, a Boston University doctoral researcher at Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, there’s been little work to figure out what causes it and why some patients have different symptoms than others.

To change that, Abur (Sargent’21) applied for and won a grant from the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. With that funding, she’s underway on a three-year study focused on Parkinson’s phenotypes, which are observable or visible traits (like how someone’s voice sounds) caused by a combination of genes and environmental factors. She’s doing the work in the Stepp Lab for Sensorimotor Rehabilitation Engineering, headed by Cara E. Stepp, a Sargent professor.

Abur, who hopes to someday start her own speech disorders research lab, spoke with The Brink about her Parkinson’s research and the clinical impact it could have.

Q&A

With Defne Abur

The Brink: Your focus will be on motor phenotypes of Parkinson’s disease. What are they?

Defne Abur: Parkinson’s disease consists of very specific changes in motor function, and recent work has suggested that there might be distinct phenotypes. One is related to instability with your posture and difficulty with walking: postural instability and gait difficulty dominant, or PIGD Parkinson’s. The second type is primarily tremor related: tremor dominant, or TD Parkinson’s. There are certain kinds of speech symptoms that are related to one phenotype and some to the other. So looking at speech symptoms by phenotype might give us more information as to whether the motor changes that are being caused by one are resulting in a very specific speech change. The primary goal of this project is to have a longitudinal study looking at speech changes within the same speakers: to look at one person over time and see how both their motor function and their speech changes to try and see if there’s a correlation.

The Brink: How are you tracking those changes—and has COVID changed your approach?

Defne Abur: We have a database with all the people with Parkinson’s who have already participated in other studies in our lab. Over several years, I’ve been collecting speech recordings, acoustic data, from them. I’m also trained in the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, a clinical assessment of motor function, which is how we classify people as being one phenotype or the other. So we have these two measures: one of their motor function and one of their speech symptoms. The idea is to have people come back in for the longitudinal aspect. At the moment, patients can still come in, but if that changes, the grant would give me the flexibility to purchase equipment to send to their homes and have them record there.

The Brink: How does this fit into your broader research?

Defne Abur: My dissertation work centers on people with motor speech disorders. I have had a focus since my first year on people with Parkinson’s disease, and I’ve been really interested in understanding why speech symptoms develop in people with Parkinson’s and how they progress. Another aspect of this grant is looking at functional speech outcomes. We know that people with Parkinson’s have speech changes and this also affects their communication in daily life. And one way that we measure that is through something called functional speech outcomes, which is where we have people listen to speech samples and rate how effective people with Parkinson’s are at getting their message across. We look at speech intelligibility and speech naturalness, and those two perceptual qualities allow us to look at how these speech symptoms might actually affect their communication in their daily lives. If someone’s speech is changing longitudinally in a large way according to our acoustic measure, we don’t know if that’s actually impactful unless we have some measure of how it affects their daily life.

The Brink: What results do you expect to see?

Defne Abur: When we collect the acoustic data, we look at two different types of measures. One is acoustic measures of voice, things like the change in your pitch, the change in the amount of noise, like breathiness. The other is acoustic measures of articulation, things like the amount of time that it takes you to read a certain sentence or how much you’re enunciating a specific consonant. We think, based on our prior work, that the speech intelligibility rated by listeners will be more affected by these articulatory features. So if we see big changes in articulatory features, we think intelligibility is going to be reduced. On the flip side, we think that if we see big reductions in measures of voice, then we’ll see changes in speech naturalness. Other research has suggested that speakers who have the postural instability and gait dominant type—the PIGD phenotype—tend to have potentially greater communication difficulties. So, our hypothesis here is that they’re going to show greater deterioration over time in these acoustic measures that we are collecting.

The Brink: How might your findings eventually benefit clinicians working with people with Parkinson’s?

Defne Abur: Currently, we don’t know which acoustic measures that we could collect in a clinic would be sensitive to people’s speech changing over time. So we really want to try to identify which acoustic measures are the ones we should be using, which ones are sensitive to speaker changes in speech intelligibility and speech naturalness—the speech outcomes that really matter for people’s daily lives. If we have some understanding of how phenotypes and speech might be related, it would inform care. Speech changes haven’t been examined with respect to the phenotype, so this is the first work that will be looking at how specific motor changes might relate to specific speech symptom development. That would then inform speech therapy: clinicians would know that when someone presents with specific motor changes, they’re likely to see a particular speech symptom develop.

The Brink: What motivates you to do this work: why do you want to help people with Parkinson’s and speech disorders?

Defne Abur: Parkinson’s is the second most common neurodegenerative disease in the world, after Alzheimer’s. Yet despite how common it is, we still know so little about how Parkinson’s is presenting in people, and specifically, how their speech symptoms are changing. We know how speech changes, but we don’t know why. And that really is like the crux of my whole dissertation and my interest in general: what is driving changes in speech symptoms? My other research, unrelated to this project, is looking at the relationships between how people with Parkinson’s perceive their speech and their speech changes: is a change in the way they perceive themselves driving a change in their speech symptoms? I really want to make sure that the research I’m doing is translational, that it can have a clinical use for people with motor speech disorders.

Speech and Parkinson’s was originally published in Inside Sargent.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.