Catastrophe & Memory

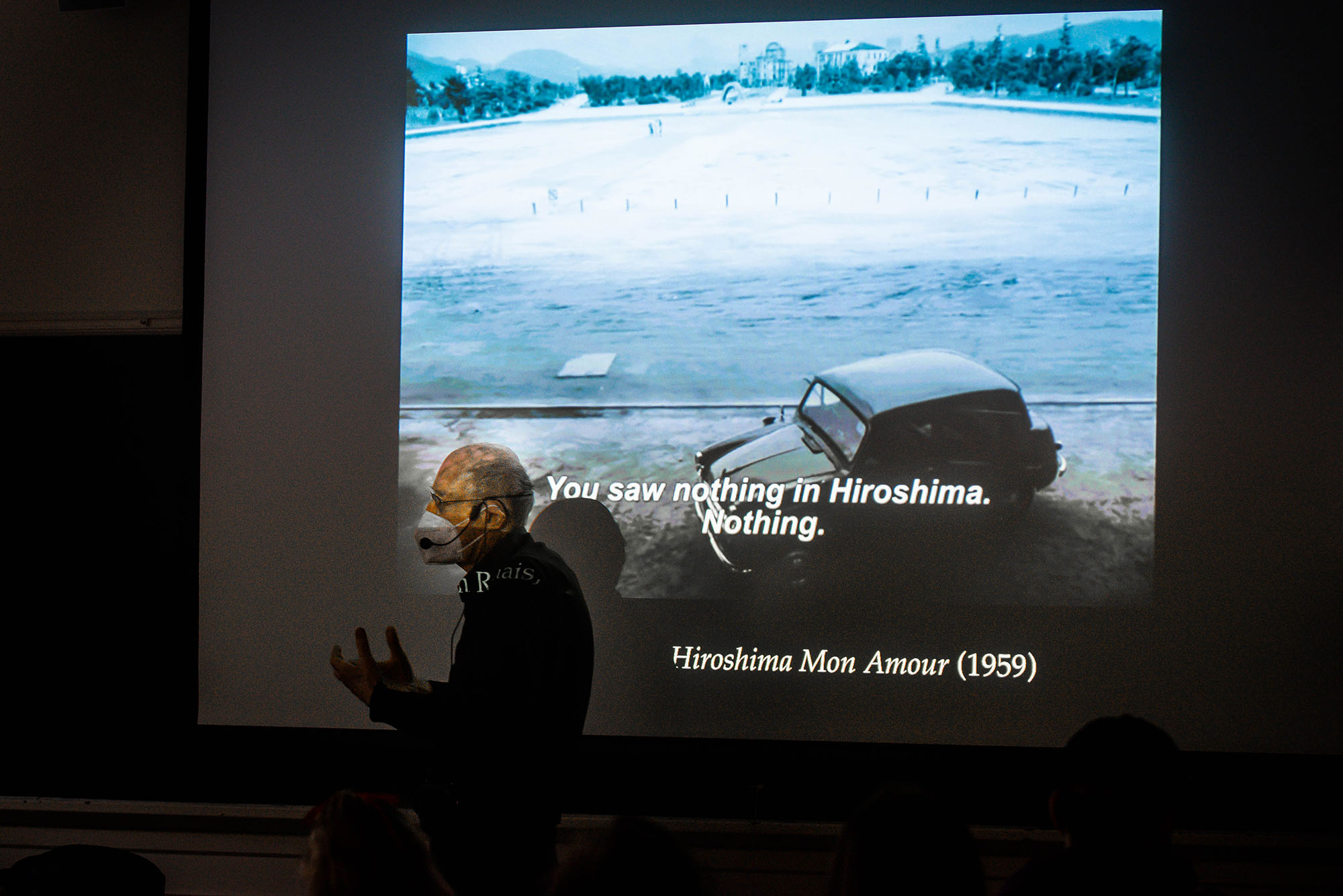

A clip from the classic 1959 movie Hiroshima Mon Amour is among the many pieces of media James Schmidt uses in his class Catastrophe & Memory.

Catastrophe & Memory

CAS class explores how society remembers—or doesn’t—when the worst happens

Today’s lesson is about Americans dropping bombs on Americans—on Black Americans, to be specific.

The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and the 1985 MOVE bombing in Philadelphia are the subjects of this session of the College of Arts & Sciences course Catastrophe & Memory.

The course is focused on “how we construct narratives that give accounts of what these unimaginable events are like,” says James Schmidt, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of history, philosophy, and political science, who teaches the course.

Over the course of the semester, the class looks at events ranging from the British memorialization of World War I (including poetry and musical compositions) to the aftermath of the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to 9/11 and the AIDS and COVID pandemics. The focus is on the ways those events become part of our “cultural memory.”

The monuments society decides to put up, Schmidt says, become “these flashing signs: Don’t forget! Don’t forget!”

He first taught the class in the mid-2000s, inspired by 9/11—(“the creepy silence of the skies in the aftermath is very hard to explain,” he says). Since then, Schmidt has found himself “furiously revising syllabus after syllabus” as new catastrophes, such as Hurricane Katrina and the Boston Marathon bombings, arrive on our doorstep.

“The new kid in town is COVID,” he says.

In today’s class, Schmidt and teaching fellow Rachel Monsey (GRS’24,’24) show black-and-white images of Tulsa and video from the MOVE incident. The rubble looks similar. With both events, some elements of society may have been more interested in forgetting than in remembering.

More than a race riot, what happened in Tulsa, Okla., was an all-out attack by whites on the thriving black neighborhood of Greenwood, known as “Black Wall Street,” where dozens were killed, hundreds injured, and 35 blocks of businesses and homes were destroyed. Credible accounts say that incendiaries—burning gasoline- or turpentine-soaked rags—were dropped on the neighborhood from more than one small plane.

The white mob was initially reported to have been “provoked,” and the events were largely airbrushed from history until the 1990s, but the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum now has extensively documented the life and fate of the neighborhood. Schmidt professes happy surprise when a few members of the class say they’d actually learned about the 1921 Tulsa massacre in high school. Although, he notes, increasing recognition of events is often inspired simply by an approaching centennial.

In Philadelphia, Pa., police trying to end a violent standoff with a group of black militants dropped two explosives on their headquarters from a helicopter, starting a fire that killed 11 of the militants and destroyed more than 60 homes, many of them belonging to African Americans. An investigative commission was convened and civil suits followed, but the only person to face criminal charges was a MOVE member, who served seven years in prison.

The key conclusion from the investigation, says Monsey, a PhD student in history, “was that the decisions of city officials would likely have not been the same if MOVE had been operating in a white middle-class neighborhood instead of a black middle-class neighborhood.” The city didn’t formally apologize for its actions until 2020, amidst America’s larger racial reckoning, and a day of remembrance was scheduled.

In 2021, a local TV reporter revealed that the remains of two of the dead, ages 12 and 14, were kept from the MOVE families and used in anthropological classes at the University of Pennsylvania and that other remains had been mishandled; Philadelphia’s health commissioner was forced to resign.

“I had never heard of the Tulsa/MOVE bombings before this course,” says Hannah Dworkin (CAS’24), who is majoring in political science and philosophy and in economics. “The fact that most people in the class—which, keep in mind, is composed of mostly political science and history majors at a high-level institution—did not know of these events is extremely telling.”

Schmidt’s classes “put the depths of human suffering at the forefront while remaining sensitive to how overwhelming the content can feel to students,” Monsey says.

The course “is a helpful reminder of how reading and learning about horrible things opens the door for a reckoning with historical blind spots,” she says. “For example, each week the students submit journal entries that not only grapple with their own blind spots, they also ask wonderfully varied questions about the role of ritualized remembering in society or about how we can hope to live in community with one another in the face of mass violence.”

When Monsey was helping Schmidt mull the latest round of syllabus revisions, she suggested adding the MOVE section, which is why she taught it. “Unlike the course’s other examples of incinerated cities,” she says, “the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 was a domestically instigated event with no foreign involvement, and racism was a catalyzing force for the violence, so it was these factors that brought the MOVE bombing to mind.”

The MOVE story “demonstrates the historical role of systemic racism in US legal policies and institutional actions,” Monsey says. “It also serves as another example, alongside 9/11, of a catastrophe doubling as a media spectacle.”

Dworkin says that the session “made me reflect on the ways in which history has been taught to me. We are often taught that the government is an entity meant to diffuse violence within this country…but these two stories are testaments of, unfortunately, the opposite. Our government is not held accountable for its actions, and actively works to erase events like this from its narrative.

“This notion, in context of the memorials and memories we’ve discussed this semester,” she says, “demonstrates a clear disconnect between what is remembered, and what should be remembered.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.