Medical Anthropologist and Physician Paul Farmer Discusses Social Class and Healthcare as Part of BU’s Diversity & Inclusion Learn More Series

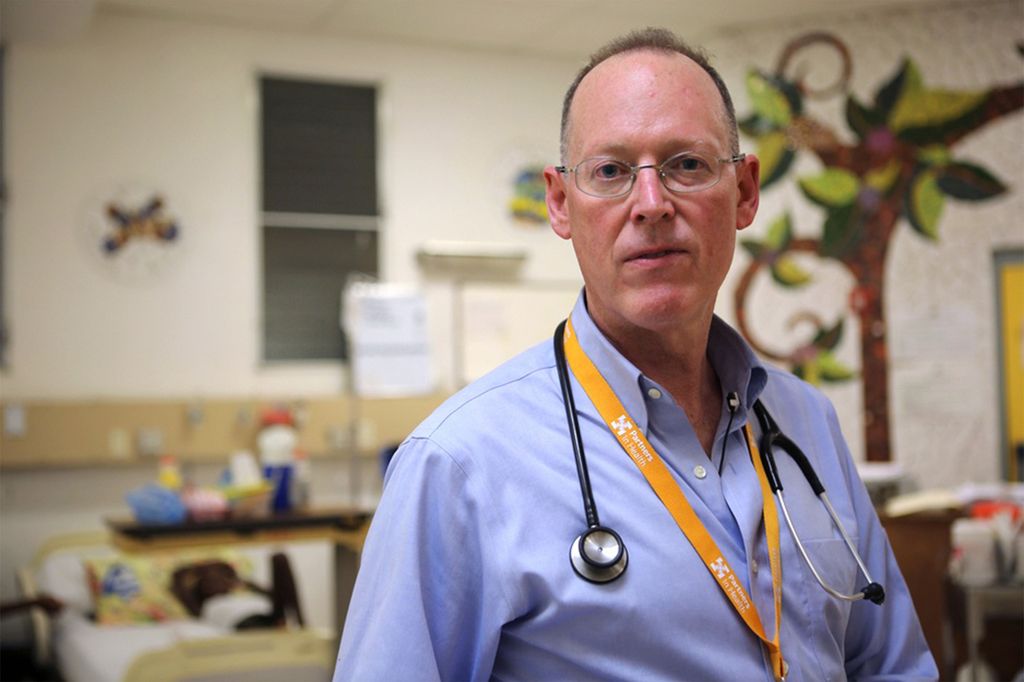

Paul Farmer is cofounder and chief strategist of Partners In Health, an international nonprofit that provides direct and high-quality medical services to those living in poverty. Photo courtesy of Partners In Health

Partners In Health Founder Paul Farmer to Speak Today on Social Class and Healthcare

Q&A with medical anthropologist and physician participating in BU Diversity & Inclusion Learn More Series

With the coronavirus pandemic, access to medical care and the ability to successfully and comfortably quarantine have highlighted the differences in social class nationally and globally. To understand how class hierarchies function in America, and around the world, Boston University’s Diversity & Inclusion (D&I) office is hosting a Learn More Series, featuring discussions exploring social class.

Paul Farmer, a medical anthropologist and cofounder of Partners In Health, an international nonprofit founded in 1987 that strives to provide medical care to the world’s poorest communities, will speak Wednesday on Social Class: A Global Perspective, which will explore how social class has been constructed on a global scale.

Farmer, Harvard Medical School’s Kolokotrones University Professor and chair of the global health and social medicine department and chief of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Division of Global Health Equity, has spent much of his career advocating for improved healthcare for the world’s most impoverished people. He and his Partners In Health colleagues have provided direct high-quality healthcare services to those who cannot afford it, advocated on their behalf, and conducted extensive research.

BU Today spoke with Farmer ahead of his September 23 talk.

Q&A

With Paul Farmer

BU Today: How does social class impact access to healthcare services? What are the most glaring disparities in global access to effective medical care?

Farmer: Variance of social class, including caste and race, are probably the primary determinants of access to care in many parts of the world. One of the contexts that I hope we’ll talk about is how social disparities are embodied as differential risks for certain pathologies. For example, take COVID-19 or Ebola and say, “How does a subaltern position in a social hierarchy put you at risk for infection?” But after that question, in this era, comes a different question: “How does that differential risk for exposure then get translated into a differential risk for bad outcomes once exposed?” There are many steps along the way where we can block that, and one of them is having strong and equitable healthcare delivery systems. That’s what I focus on in my work.

From your perspective, what is the most effective way to equalize access to medical services among all social classes?

If we focus on people who are shut out of the system, and the primary determinant is social class, then that will be the best intervention that we could make. Sometimes it’s rural vs urban, women and girls vs everybody else, people who are living in poverty vs the nonpoor—so there are lots of different ways to describe that, to focus preferentially on those who are excluded. Inside the work of Partners In Health, since the ’80s, we’ve used the expression of “preferential option for the poor,” which comes from Latin American liberation theology. If the healthcare system doesn’t use that term “preferential option for the poor,” but they say that they’re focusing on the bottom quintile, meaning the lowest fifth in terms of income and resources, you still get the same output. So to go back to that original formulation, you ask, “What are the interventions you can make?” I would say that the number one intervention is to focus on the excluded. So, if I go back to COVID-19, and you say, “People of color are at a much greater risk,” I’m asking, “Why and how, and where can we block that along the way?” Just imagine if we had a healthcare delivery system that focused primarily on the most vulnerable and the most at-risk, then we would be many steps further along in addressing the disparities. I’m not saying it’s easy, I’m just saying that there’s no reason to believe that this is impossible.

What has the coronavirus pandemic revealed about global economic inequality, social class, and access to healthcare?

I think it’s done on a global scale what a lot of epidemics in the past have done. I’m hoping to talk a lot during my discussion about Ebola in West Africa. In that instance, there was never a pandemic. It really remained largely in three countries: Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea, but even then, the lessons were clear that every form of social inequality has a cost in terms of good health outcomes. So that was a lesson we learned with Ebola, but that was also a lesson we learned with AIDS, with Zika—it goes on and on. So, I think we’re learning these same lessons again now with COVID-19 on a global scale. In India, you see migrant laborers who got stuck in the shutdown, and that didn’t happen on such a grand scale in the United States, but it happened nonetheless, where migrant workers were in increasingly difficult circumstances because of COVID-19. You’re seeing the same lessons again and again, and that is that pandemics reveal a lot about our social pathologies.

Paul Farmer will speak on Social Class: A Global Perspective, part of the Diversity & Inclusion Learn More Series, on Wednesday, September 23, at 10 am. Register here to attend virtually.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.