Mining Bobby Orr

Mining Bobby Orr

BU’s Thomas Whalen celebrates hockey great and the Big Bad Bruins of 1970 in new book

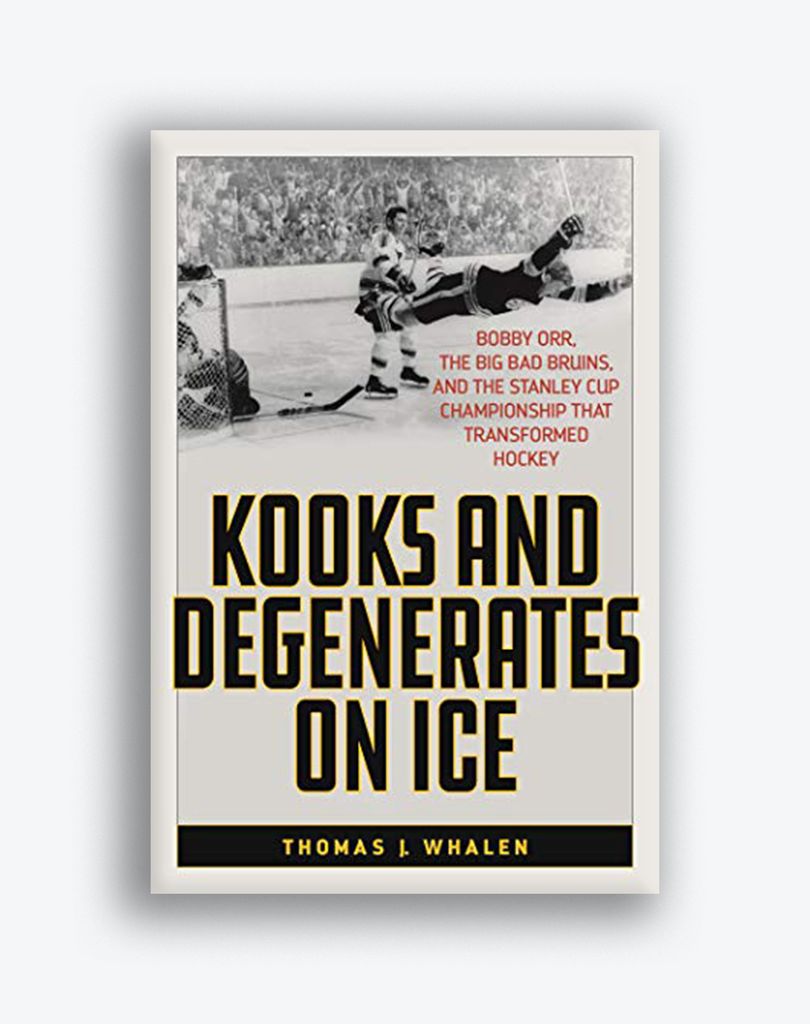

Boston Bruins defenseman Bobby Orr is airborne after scoring the goal that won the 1970 Stanley Cup, May 10, 1970. Photo by Ray Lussier/The Boston Herald via AP, File

Say “Bobby Orr flies through the air” to someone who grew up a Boston sports fan and watch them smile.

May 10 was the 50th anniversary of one of the greatest moments in Boston sports history. On that date in 1970, Orr scored the winning goal against the St. Louis Blues in overtime at the old Boston Garden to win the Stanley Cup for the Boston Bruins for the first time since 1941. A Blues player hooked Orr’s skates out from under him as the puck went into the net, sending Orr soaring through the air like Superman.

Many thought he was.

“As big as Tom Brady and Gronk and the Patriots dynasty were for the last two decades, no way does it even compare to what Bobby Orr and the Bruins had in the early 1970s, not even close,” says Thomas Whalen, a College of General Studies associate professor of social sciences. “The Bruins were it.”

As a boy, Whalen had the poster of Orr’s iconic flight on his bedroom wall. Now his new book, Kooks and Degenerates on Ice: Bobby Orr, the Big Bad Bruins, and the Stanley Cup Championship That Transformed Hockey (Rowman & Littlefield, 2020), documents that famous moment, all that led up to it, and all that followed from it. The book completes a trilogy of Boston sports books by Whalen: Spirit of ’67: The Cardiac Kids, El Birdos, and the World Series That Captivated America (Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), about the Red Sox “Impossible Dream” season, and Dynasty’s End: Bill Russell and the 1968-69 World Champion Boston Celtics (Northeastern University Press, 2003).

Boston was one of the original six National Hockey League cities, but by the mid-1960s, the Bruins hadn’t won the Stanley Cup in a quarter-century or even made the playoffs in a decade. Rabid Bruins fans had little to cheer about until 18-year-old Robert Gordon Orr from Parry Sound, Ontario, joined the team in 1966, donned a number 4 sweater, and began making history. He was named the league’s outstanding rookie in his first season and broke the goal- and point-scoring records for a defenseman in the 1968-69 season. More important than the numbers, no defenseman had ever played both ends of the ice that way, or looked so graceful doing it.

“Bobby Orr was like Gene Kelly on ice—he was just magnificent,” Whalen says.

By the time the 1969-70 season began, Orr had been joined by a cast of characters worthy of a disaster movie, players whose attitude and playing style made them the Big Bad Bruins. Center Phil Esposito camped in front of the opposition’s net, immovable, until a puck appeared that he could whack past the goalie. A popular slogan at the time—what we’d call a meme today—was: “Jesus Saves, and Espo Scores on the Rebound.” Bruins goalie Gerry Cheevers never hesitated to mix it up with an opposing player and drew stitch marks on his mask with a marker whenever he took a puck or a stick in the face. And then there was hard-partying center Derek Sanderson, who was even flashier off the ice than on it, sporting a big moustache and a fur coat as he palled around with NFL star Joe Namath. Sanderson was the first hockey player to seem a little bit groovy.

You never doubted that he was what he was, a really decent person with a big heart who just happened to be the greatest hockey player that ever laced a pair of skates.

The times were difficult. The war in Vietnam raged on, protestors fought with cops, and Richard Nixon was president. People were looking for distraction, just as they are today, Whalen says, but other Boston sports teams weren’t providing it in 1969 and 1970.

“The Red Sox by 1970 were kind of a middle-of-the-pack team, and the Patriots were a complete and utter joke,” he says. “The Celtics were entering the post-Russell years, but even when they were winning all their championships in the ’60s, no one was attending their games anyway. So the Bruins had a monopoly on fan interest.”

In those days, before cable and the internet, entertainment options were fewer. Kids played street hockey on every block with a plastic puck or a taped-up tennis ball, and most every one of them wanted to be Bobby Orr.

Newspaper photos of Orr’s championship flight were captured by several photographers, but the late Boston Record-American photographer Ray Lussier had the perfect angle and his iconic shot would quickly be turned into a poster that hung on many bedroom walls besides Whalen’s (and this writer’s).

The Bruins won another Stanley Cup in 1972, but Orr’s career thereafter was cut short by injuries, and he retired in 1978, after leaving Boston to play parts of two seasons with the Chicago Blackhawks. By then, he had not only changed the way the game was played, but had become the first player to bring in a hard-charging agent for contract negotiations.

Perhaps more important, the popularity of Orr and the rest of the team brought a boom in rink construction and youth hockey across New England and beyond. Among devoted Bruins fans were several future members of the 1980 US Olympic “Miracle on Ice” team, which included Terriers Jim Craig (Wheelock’80, MET’09), captain Mike Eruzione (Wheelock’77), Jack O’Callahan (CAS’79), and Dave Silk (CAS’80, MET’92, Questrom’94). It’s not an exaggeration to say that the NHL and hockey’s popularity today is in some significant way Orr’s legacy.

Although he had a role in some memorable escapades detailed by Whalen, Orr was never exactly one of the Kooks and Degenerates among his teammates (the description comes from backup goalie Eddie Johnston). And his post-hockey life has been exemplary.

“He’s like hockey’s version of Roy Hobbs in The Natural,” Whalen says. “You don’t hear bad things about Bobby Orr. He is a genuinely good person, and he’s involved in his community. You never doubted that he was what he was, a really decent person with a big heart who just happened to be the greatest hockey player that ever laced a pair of skates.”

Whalen’s connection to the Bruins spans eras. The son of an avid amateur hockey player, he was just a boy when he met Orr at a promotional appearance at a North Shore mall. A few years ago, he taught future Bruin Charlie McAvoy in a BU class on US foreign policy. He says the days of a Bobby Orr are unlikely to be repeated.

“Orr was kind of like Michael Jordan on ice,” Whalen says. “You never knew what you were going to get. There’d always be some unbelievable new move that you never saw before, and frankly, haven’t seen since.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.