MET Class Offers Lessons in the Power of Language to Remake the World

MET Class Offers Lessons in the Power of Language to Remake the World

In midst of pandemic and protests against racism, course expands to include lectures from activists and artists on how they’re responding to this moment in history

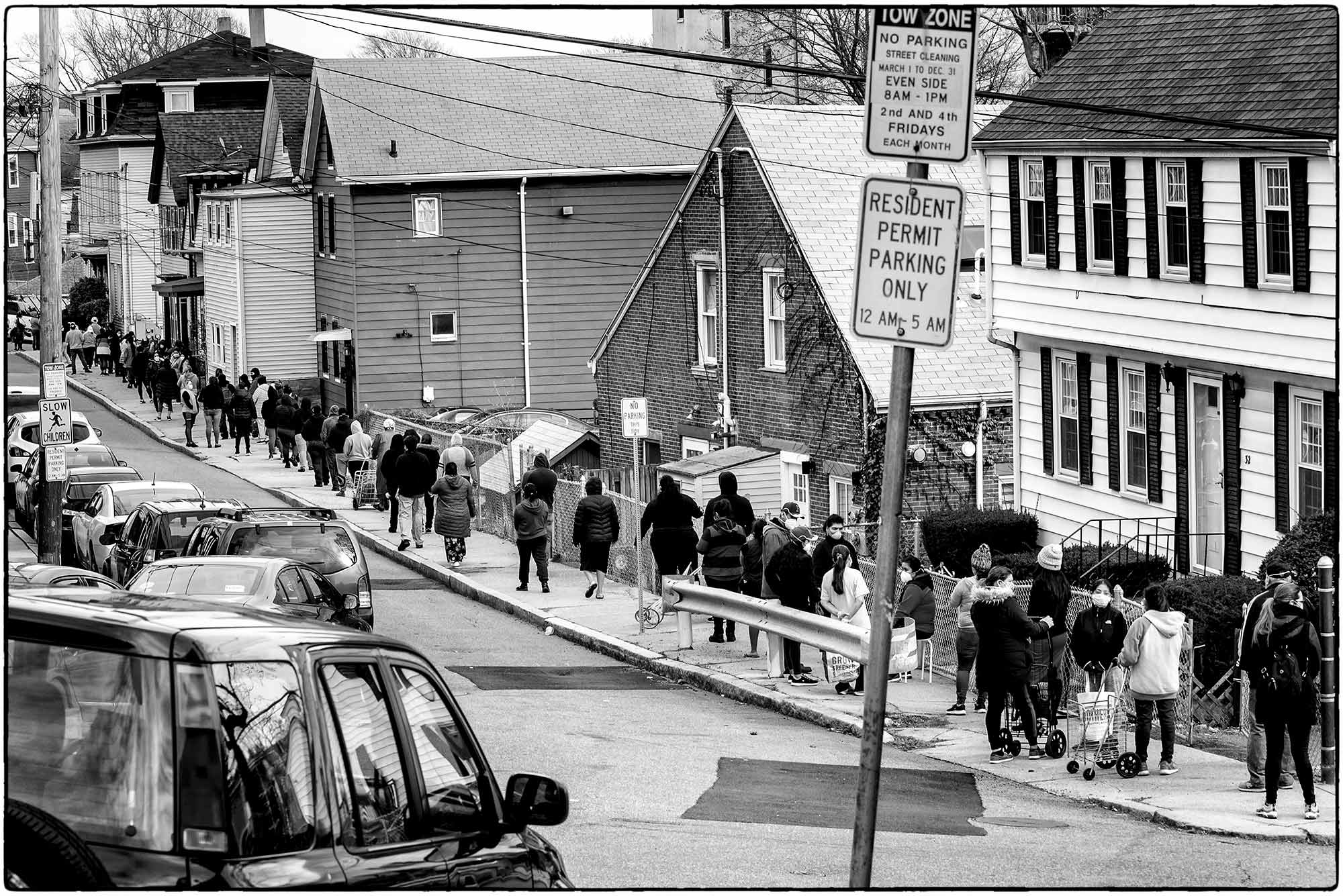

Darelene DeVita discussed her pictures of Chelsea, Mass., grappling with the coronavirus pandemic as part of Art of Rhetoric in Life and Work, a Metropolitan College class taught by Megan Sullivan. Photo by Darlene DeVita

“Chelsea was hit extremely hard” by COVID-19, photographer Darlene DeVita says by Zoom to nine Metropolitan College students. With a population that’s two thirds Hispanic, the city is among the most diverse communities in Massachusetts, and DeVita has captured her hometown in what might be called a pictorial Journal of the Plague Year.

Her People of Chelsea project, begun in 2016 to record her community, has entered its “COVID edition,” she says, as she screens snapshots of pandemic life: hundreds of people lining the streets awaiting food from a makeshift pantry at a local café after mass layoffs plunged residents into desperation, bags and bags of produce stacked at that café, and individual portraits, like that of a masked Gladys Vega, CEO of the advocacy and assistance group Chelsea Collaborative, who handed out food from her own home to people in need.

“Living here was a little scary,” DeVita tells the students. “I have asthma. My husband was not wanting me to go out there and photograph. I was nervous, because the thought of it hitting my lungs—very scary. But I couldn’t sit around anymore. I just had to get out and see what was going on and share this story.”

Her doggedness was well worth it, according to the students in MET’s Art of Rhetoric in Life and Work class. “This is really a beautiful intersection of your art and your vision for social justice,” Theresa Goh (MET’21) tells DeVita during a follow-up Q&A. “Fantastic stuff,” agrees Jason Fanstone (MET’21).

Megan Sullivan’s class usually is about “writing that matters,” meaning focused on social change, says the College of General Studies associate professor of rhetoric. (She teaches the class as a MET offering.) But during this summer, affected by viruses both medical and racist, she says, “the course is also exploring how other artists use their medium to do the same.” And nonartist activists as well: the class has also heard from Ben Hires (CAS’00, STH’03, MET’08), CEO of the Boston Chinatown Neighborhood Center, and Kerry Thompson from the Disability Rights Center.

“I couldn’t sit around anymore. I just had to get out and see what was going on and share this story.”

COVID-19 has disproportionately pummelled communities of color, making tragically topical the theme of the course, which Sullivan created seven years ago. As director of the CGS Center for Interdisciplinary Teaching & Learning, she cochairs an inclusive pedagogy initiative and has “become increasingly knowledgeable about something I always believed in—creating more inclusive classrooms,” she says. “Schooling myself further in inclusive pedagogy has meant that I have to think anew about everything I teach, so that informed my desire to talk more about race and COVID-19.”

Since her syllabus includes Notes of a Native Son, the 1955 essay collection on race by James Baldwin, who has become a go-to read in these days of antiracism protest, “it seemed natural to think about including Black Lives Matter into the course,” Sullivan says.

The students also read “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” written by Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59) after his imprisonment in Alabama for civil rights activism in 1963. “When we discuss [King’s] use of rhetorical terms such as logos, ethos, and pathos,” says Sullivan, ”I want them to always remember that King used his intellect, knowledge, and logic to differentiate between just and unjust laws, that when he implores his readers to consider how they would respond as a Black father who must tell his daughter why she cannot be admitted into a local amusement park, he is appealing to a reader’s emotion or pathos.

“‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’ is one of the 20th century’s most persuasive documents, and I want students to see why it changed how we live, and how they can write about what matters to them.”

Other readings include Alice Walker’s In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose (“a plea to value Black women’s writing,” says Sullivan) and Virginia Woolf’s essay on “Shakespeare’s Sister” (which argues “that women need money and a room of their own to write”).

The key lesson of the class, she says, is the power of language in remaking the world.

“I hope that when they leave the class, students know that they too can use their writing and speaking to make social change,” Sullivan says. “I also want them to know that what they learn in the classroom is relevant to their current lives.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.