Google Data Reveals Which Policies Best Promote Physical Distancing

Policy limits on bars and restaurants were associated with the greatest reduction of population mobility, a new BU study indicates. Photo by SolStock/iStock

Google Data Reveals Which Policies Best Promote Physical Distancing

BU public health researcher Gregory Wellenius partnered with Google to analyze the effects of city and state government policies, advisories

Social distancing (or “physical distancing”) mandates have been the main way that state and city governments are curbing the spread of the novel coronavirus. But how much do declaring states of emergency, implementing stay-at-home orders, shuttering non-essential businesses, and other policies and guidelines actually keep people from moving around and coming into contact with each other?

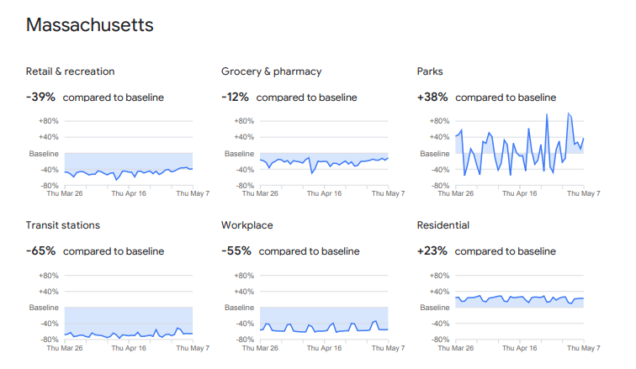

State mandates intended to promote physical distancing—especially limits on bars and restaurants—do reduce the amount of time people spend away from their places of residence, according to a new study by Boston University School of Public Health (SPH) researcher Gregory Wellenius, who collaborated on the work with Google as part of its COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports project.

Wellenius began a short-term position as a visiting scientist at Google Research in January. Much of his research uses new technologies and data sources to better understand and address the harms of climate change.

“When the COVID-19 pandemic started, it was really a natural fit for our team to start brainstorming ideas about how Google could contribute meaningful insights to help guide the global public health response to the pandemic,” he says.

The team soon launched the COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports, and began using the data for research, looking for insights that could be useful to the pandemic response.

The study, available via preprint on arXiv, finds that state-of-emergency declarations resulted in a 10 percent reduction in time spent away from places of residence. The implementation of one or more physical distancing policies resulted in an additional 25 percent reduction (and a 33 percent reduction in visits to retail and recreational locations), and subsequent shelter-in-place mandates led to an additional 29 percent reduction in the time that people spent out and about.

“The limits on bars and restaurants seems to be the single policy that was associated with the greatest reduction of population mobility,” says Wellenius, director of SPH’s Program on Climate and Health.

However, he notes that states with a combination of orders saw the biggest reductions in how much time people spent away from their places of residence and moved around, where they could potentially contract or transmit the coronavirus. The report also revealed that, compared to baseline data from before the pandemic, people were spending significantly more time in parks.

The reports use anonymized data (and cutting-edge differential privacy measures, which Wellenius and colleagues outlined in another recent paper) from users that have opted in to this service, in much the same way that Google Maps shows how busy a particular location is. The Community Mobility Reports use these anonymized data to map trends in how the COVID-19 pandemic—and state-level policies to control it—are affecting where people are spending more or less time.

The new paper is the first of several that may come out of the project, Wellenius says. “A reasonable question for a local official or governor to ask is, ‘Which of these policies, or combination of policies, will give us the results that are best suited to the pandemic here, and the economy here, and the public health here in my state?’” Wellenius says. He and his Community Mobility Reports collaborators are now working to provide more location-tailored information to help answer those questions.

“The ability to bring to bear so many resources on a focused problem so quickly is truly remarkable,” he says. “I see tremendous potential for collaborations between technology companies that have these engineering abilities and resources on the one hand, and academics and public health professionals who can inform and guide that research in the most meaningful ways possible.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.