As Coronavirus Exploded in Boston, BU Class Trip to US-Mexico Border Grappled with Evolving Ethics

Pictured here is the Rio Grande, at the edge of the Lower Rio Grande Valley National WildLife Refuge–land that is currently under threat by President Trump’s proposed border wall extensions. Standing on the Texas side of the river, BUSPH student Josh Licursi and the rest of the class looked across the river to Mexico, directly on the other side.

As Coronavirus Exploded in Boston, BU Class Trip to US-Mexico Border Grappled with Evolving Ethics

BU health ethicists and students found themselves navigating a rapidly changing situation while visiting border communities in Texas

In mid-March, as the spread of the novel coronavirus began accelerating across the United States, a group of 12 Boston University School of Public Health students and three professors were navigating their way through Texas’s Rio Grande Valley on the US-Mexico border. They were there to learn about the region’s vast migrant population and ongoing public health crisis on the border, a situation that has only grown more dire over the last year. Meanwhile, their phones kept ringing with news from friends back in Boston, over 2,200 miles away, relaying that Trader Joe’s was running low on food and toilet paper, and BU classes and conferences were being cancelled as coronavirus cases popped up in the city.

The approaching pandemic almost jeopardized the trip entirely. Just days before the group left for Texas, BU had suspended all international spring break trips and other large gatherings, leaving their class trip—the first of its kind offered by BU—in uncertain fate. But the group received the okay from BU’s Global Programs to depart as planned for Texas, preparing themselves for the possibility that they would be required to self-quarantine for 14 days upon returning to Massachusetts.

After arriving in Texas, nothing that the students had already covered in their BU School of Public Health course, Health and Human Rights on the Border, led by health ethicists and human rights advocates George Annas and Sondra Crosby, could prepare them for witnessing the border’s humanitarian issues firsthand. Team leaders Crosby and Annas were joined by Serena Rajabiun, professor of public health at UMass Lowell, who assisted with every level of the planned learning modules and day trips to the border towns.

While there, Crosby and Annas planned to cross the border into Mexico to conduct a field assessment of the large refugee camps based in Matamoros, Mexico. But since refugees and migrants living in refugee camps are particularly vulnerable to any infectious disease outbreak like COVID-19, the trip suddenly took on a whole new set of moral dilemmas as the COVID-19 crisis evolved rapidly while the group was on location in Texas.

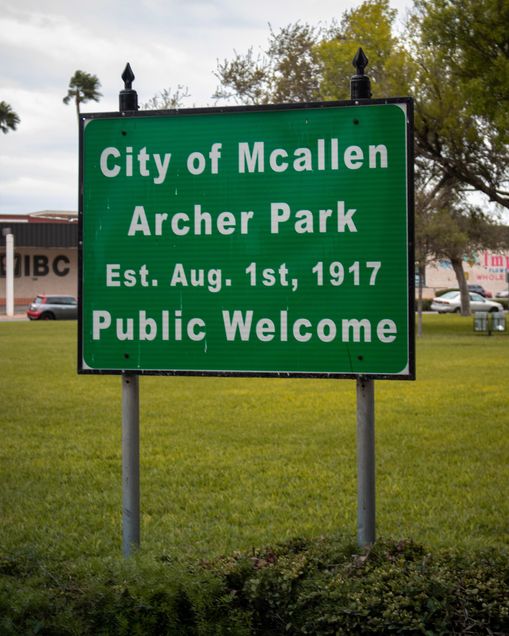

The class landed in McAllen Texas, on March 9, 2020, and kicked off their trip together with a hearty Tex-Mex meal at a local restaurant.

“It’s more critical than ever in the pandemic of COVID-19 to carefully examine our actions and their consequences,” says Annas, a William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor and director of SPH’s Center for Health Law, Ethics & Human Rights. It was his first time visiting the border.

Though no one in the group was ill and they were traveling in an area where COVID-19 had not been reported, the group was keenly aware that if anyone could possibly expose the communities on the border to the virus, it was them. The group had recently traveled from the heavily populated Boston metro area, from which coronavirus cases had begun to spread like wildfire.

“Any kind of work that involves human rights is going to be constantly changing,” says Crosby, who has traveled to conflict zones around the world documenting torture and human rights violations. She’s an SPH associate professor of health law, ethics, and human rights who also works as an internist at Boston Medical Center—the teaching hospital of the BU School of Medicine—specializing in internal medicine.

“I conceived this course because I believe fieldwork is critically important to learning about and understanding human rights,” Crosby says. “You always have to prepare to be flexible.”

On Monday, March 9, in the heat of the late afternoon, the group checked into their hotel in McAllen, Texas, a small city in the Rio Grande Valley that fuses the languages and cultures of Mexico and the US. Back in Boston, it was BU’s first day of spring break. In McAllen, the streets outside the hotel were filled with food trucks serving authentic Mexican cuisine. The students prepared themselves for a busy week of 10- to 12-hour days of learning modules and volunteering—and eating delicious, authentic tacos at every meal break they got.

The next morning, on March 10, the group hit the ground running. Their first full day started with breakfast and a tour of the city, followed by a group visit to Catholic Charities, a shelter for migrants released from US Customs and Border Protection. It serves as a resting point for people and families on their journey to their final destinations in the US, where they will await their asylum hearing. They were greeted by the executive director, Sister Norma Pimentel, known for her humanitarian work in the region, and met with the nurses and clinicians serving people on their journey. The students spent the day serving meals, inventorying supplies, and volunteering in other ways as part of the course.

“It’s a shame that the novel work happening to make the situation at the border better is completely getting lost in the loud rhetoric of migrants being criminals and drug addicts,” says Gopika Das, a student on the trip, who always knew her life path would involve working with immigrants.

Das was particularly moved by the work of Gaby Zavala, who manages Resource Center Matamoros, a nongovernmental organization based on the other side of the border in Matamoros that coordinates support for the refugee camp in the city, and is run by refugees themselves. Das and the other students met Zavala for breakfast the following morning, before heading out to explore Brownsville, Texas, about an hour away from their hotel.

In Brownsville, the group saw the border wall for the first time.

“We had been talking about this wall, this border, all semester, learning about it,” says Josh Licursi, a BU student on the trip. “To be sitting, having a class on the ground in front of it with Mexico right behind us, was pretty incredible.”

Licursi says the wall was made of metal slats, with a deep ditch on the other side, making it virtually impossible to climb. The opportunity to visit the border drew him to sign up for Annas and Crosby’s course in the first place, feeling that, as a health professional, if he wants to work with communities different than himself, he had to get field experience firsthand.

While sitting cross-legged in the Texas heat, the class heard from BU School of Public Health alum Sera Bonds (SPH’04), who regularly volunteers her time to support migrants in the Brownsville area. With Matamoros just beyond the wall, Bonds talked with the students about the importance of antiracism, and the difference between asking people what they need as opposed to telling people what they need. She also challenged students to question the commonly held assumption that the presence of a large group of students, or volunteers, is automatically helpful to the community.

On Wednesday, March 11, the class sat in a circle listening to a lecture by local volunteer and BU School of Public Health alum Sara Bonds, on volunteerism and anti-racism at the border fence in Brownsville, Texas. The class explored other areas near the border fence and toured the Brownsville town square, pictured above.

Crosby seconds that mentality. “Travel across borders and volunteerism is a luxury of privileged groups, and a form of neocolonialism, where often the people we intend to help have no, or at least an unequal voice, as to whether they want our help,” she says.

“There’s really nothing a group of master’s students like us can do for [this community] besides use our social networks to advocate and raise funds for them,” says Das, reflecting on the lecture.

Looking beyond the metal fence, Das, Licursi, and the others witnessed families bathing themselves in the Rio Grande, huddled by the river.

“Not far from that area there are tents set up with thousands of people waiting in terrible conditions to have their asylum hearings or to get into the country in general,” Licursi says, remembering the sight of the families in the river. “It sank in that this is why we’re here, to understand the real problem.”

Back in September 2019, Crosby had visited the migrant encampment directly across the border from Brownsville, where she documented alarmingly unsafe, unsanitary, and inhumane conditions. Speaking with the group, Bonds shared new reports that infrastructure had improved since Crosby was last there, but stressed that “it is still a horrible situation for families to be in.” This time around, Crosby planned to compare the current situation with the one she had seen in September, bringing Annas and Rajabiun along to assess the situation in the camps for the first time themselves.

It’s a shame that the novel work happening to make the situation at the border better is completely getting lost in the loud rhetoric of migrants being criminals and drug addicts.

But coronavirus would dash those plans. On that same afternoon that Bonds gave a lecture in front of the Brownsville border wall, the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a global pandemic, and BU and other universities in Massachusetts announced that all classes would take place remotely for the indefinite future. With the threat of coronavirus growing more and more pronounced, Crosby, Annas, and Rajabiun had to decide whether traveling to the encampment was a wise decision, or if they should stay back with the students, who were not permitted to cross because of safety concerns of crime and kidnapping, outlined in a US Department of State travel advisory for Tamaulipas, Mexico, where Matamoros is located.

“Ultimately we decided it would not be ethical to expose the camp to US visitors, no matter how low the actual risk [that we were carrying the coronavirus],” Crosby says, pointing out that people living in the refugee camps don’t have the option of implementing protective measures, nor is anybody monitoring the volunteers visiting the camps for fever or other coronavirus symptoms. Crosby and Annas say it’s unknown how the crisis will impact humanitarian aid at the border.

On their day in Brownsville—known as the taco capital of the world—the group wrapped up a learning module with an early dinner at “El Ultimo Taco.” Later that evening, the class debated the ongoing US Supreme Court case about the Trump administration’s controversial “return-to-Mexico” policy. Meanwhile, that same day—buried under the landslide of news about the coronavirus pandemic and government response—the Supreme Court reached its verdict, allowing the policy to stay in effect, forcing about 25,000 asylum seekers to remain in Mexico—a blow to refugee advocates fighting for the policy to be upended.

While learning in Texas, the group continued to hear how swiftly the coronavirus was upending life in Boston through phone conversations and texts with friends and colleagues.

“We talked about the pandemic pretty constantly, updating each other with new news [we heard from back home],” says Licursi. Despite the perceived relatively low risk at that moment, the students and professors followed US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines on washing hands, using hand sanitizer, and regularly taking note of their own health.

On Thursday, March 12, their last full day in Texas, the class spent the morning in McAllen’s main medical clinic, which provides care to locals, including undocumented immigrants and migrants. They had planned to interview patients with HIV, but changed their plans in light of the snowballing number of coronavirus cases popping up around the country.

Travel across borders and volunteerism is a luxury of privileged groups, and a form of neocolonialism, where often the people we intend to help have no, or at least an unequal voice, as to whether they want our help.

“It would not have been ethical to proceed as we planned,” says Annas.

Instead of meeting patients with HIV, who are immunocompromised and at greater risk from coronavirus, they met with clinicians and healthcare workers at a long table, keeping an ample amount of distance, but still getting the opportunity to learn from practitioners about the health issues facing the border community.

After their lesson at the clinic, the class took time to visit the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge, a protected area just 15 miles south of McAllen, which has recently become threatened by Trump’s border wall construction plans. On their way back to their hotel in McAllen, the group stopped on the side of the road to get one last glimpse of the intimidating border wall.

The van stopped, and they stepped out into the heat. A student caught sight of something in the shrubs along the road. Slowly, one by one, the group realized they were looking at a pile of hastily abandoned belongings: a child’s toy, baby food, and adult-sized clothing were strewn on the ground, alongside a clear plastic bag stamped with the words, “Department of Homeland Security.”

The border wall as seen from a road in McAllen, Texas. On their last full day of the trip, the class found a family’s belongings hastily abandoned near the border wall in McAllen, leaving a disturbing last impression on the students.

“When we first saw it, we couldn’t make sense of what we were seeing,” says Das.

It appeared to be a fleeing family’s necessities. The group fell silent, struck by knowing that, somewhere out there, a family was going without their clothes and baby food. And they were powerless to help them. They lingered a bit longer, processing the moment, then got back into the van to continue driving.

“It was the last thing that we really saw,” before leaving Texas, Das says. “A sobering reality.”

Annas, Crosby, Rajabiun, and the students debriefed on their last night, processing and reflecting on the journey—what they saw, what they learned, what they heard.

“It was an emotionally exhausting five days, each one more powerful than the last,” Das says.

“My hope is the students took away that human rights work requires grit, flexibility, compassion, respect, and humility,” says Crosby.

After debriefing, they walked to a group of food trucks serving dinner. They sat at a long table, replenishing themselves with tacos and fresh juice a local vendor was generously handing out free of charge. Licursi and Das sat next to each other, eyes widening in delight every time they heard the blender start up again, knowing any second the kind vendor would bring even more juice to the table despite their insistence that they had drunk their fill.

As a first-year Master of Public Health student, Das says her time in Texas confirmed her aspirations to work in human rights law.

“We asked ourselves, as public health professionals, what does it mean to ethically travel to a place like this?” says Licursi, who felt the lessons they learned on the trip—between watching Annas and Crosby make on-the-fly decisions with ethics in mind and learning from members of the local community—can be applied everywhere.

“This trip really showed us that it takes mobilizing the community, as opposed to having someone from outside the community come in to make the changes you want to see,” he says. “And that can be applied everywhere.” After graduation, he hopes to work in health communication, specializing in visual mediums like video and photography.

The group returned to Boston as originally planned, on Friday, March 13, with no delays or issues. They were not screened at the airport for fever or cough. But from the moment they set foot outside the airport, it was clear to them that everything about daily life in Boston had changed.

“When we landed in Boston, it was like the apocalypse,” says Crosby. Since returning, she has been on the front lines of patient care at Boston Medical Center, screening patients for COVID-19 infections—all while continuing to teach alongside Annas and Rajabiun online, learning Zoom on the fly.

“It has been full steam ever since,” she says.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.