Physics for All: An Online Class Is Expanding the Gateway to STEM

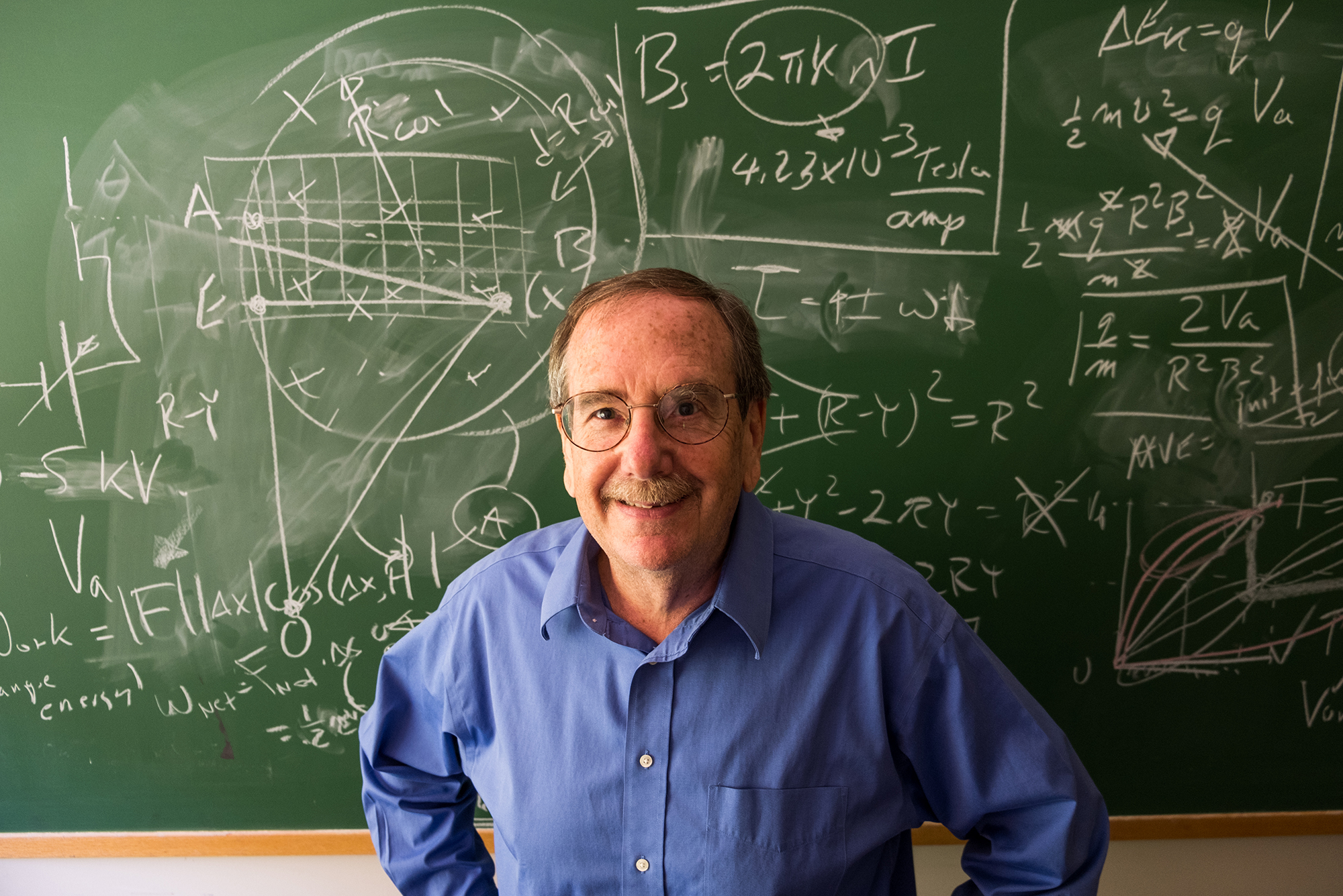

Mark Greenman has developed an online AP physics class—a gateway to STEM college programs and careers—for students who attend high schools that don’t offer such a course. Photo by Cydney Scott

Physics for All: An Online Class Is Expanding the Gateway to STEM

BU physicist creates online AP physics program for underserved high schoolers

A group of high school students huddles together to wrestle with a question that their normal coursework isn’t asking of them: how do we find the potential energy of a spring? Mark Greenman, a Boston University College of Arts & Sciences physics research fellow, won’t give the seven students the formula—but he will help them discover it for themselves.

Greenman is the director of Project Accelerate, a program designed to provide a rigorous Advanced Placement (AP) physics curriculum to high school students in school districts that don’t offer the class. AP physics is often considered a “gateway course” because it gives students foundational knowledge to help them pursue and ultimately succeed in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) careers. But, Greenman says, this gate is currently closed to many in low-income communities that don’t have the resources to offer the course to their public school students.

“There are literally thousands of schools across the nation that don’t offer this level of physics education to their high school students,” he says.

So, inspired by his colleague Andrew Duffy, a CAS master lecturer in physics and winner of the 2012 Metcalf Cup and Prize, the University’s highest teaching honor, who developed an online introductory physics course for college students, Greenman decided to create a similar-style program—but instead, with high school students in mind.

A year (and nearly 2,000 hours of work) later, Greenman and Duffy set the program, which they named Project Accelerate, into practice with seed funding from BU Digital Learning & Innovation. Starting off, they weren’t sure how well it would prepare high schoolers for the ultimate test: passing the AP physics exam. Still, they believed their idea had promise—and so did the National Science Foundation (NSF), which provided funding for them to offer the course as a pilot study to assess its effectiveness. Partnering with seven high schools across Massachusetts, Greenman and Duffy initially rolled out Project Accelerate to 24 students who didn’t have access to an AP physics course through their school.

[Project Accelerate] taught me something that no other [course] had up to that point: what it felt like to really be academically challenged, and how to overcome that.

All the students who completed the program went on to take the AP physics exam and the results were encouraging: Project Accelerate students outperformed their peers who had taken AP physics in a traditional classroom. Not long after the pilot study, the NSF awarded Greenman and Duffy three more years of funding.

So how does Project Accelerate work? Each high school that wants to offer the program to its students appoints a liaison, typically a teacher, who provides students with encouragement and helps them stay accountable to their Project Accelerate coursework and deadlines. Likewise, BU also assigns University liaisons—typically physics educators—to provide mentorship to students. Meanwhile, students complete engaging online modules to help them learn the concepts, and they solidify their understanding through graded homework assignments and quizzes. Throughout the course, they’re expected to interact with each other in person (when possible) and through an online discussion forum.

Most students also participate in hands-on labs at their high school, or if they’re local, commute to BU to participate in lab sessions. Greenman doesn’t often have the privilege of leading the hands-on labs, as the labs are typically run by graduate-level teaching assistants. So on one particular day when he subbed in to work with several students, he says, “It was true joy for me to be able to be with [my students], to listen to them, and to watch how they try to approach the labs.” With Greenman’s guidance, every participant in the session was able to derive the formula for the potential energy within a spring—a value that depends partly upon how much the spring is stretched.

“The instructors encouraged students to help each other with problems before they would step in,” explains West Virginia University sophomore aerospace engineering major Matteo Cerasoli, who participated in Project Accelerate during the 2017–2018 school year. “And I enjoyed that because I actually found there was a lot more interaction in that course than in most normal high school courses.”

Project Accelerate “taught me something that no other [course] had, up to that point: what it felt like to really be academically challenged, and how to overcome that,” he adds. “Now I’m taking the equivalent of Physics II in college, and the knowledge that I learned from Project Accelerate is still applicable.”

Greenman hopes so too, and he notes that the program has expanded steadily since its launch. Over 100 students have already completed the course, and this year, over 100 more students across 25 partner high schools are participating. If the two BU physics teachers continue to receive funding, Greenman aims to reach an even greater number of students in the years to come—perhaps 500 to 1,000 nationwide, he says.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.