Lobsters on the Line

Biologist Kari Lavalli learns what’s killing crustaceans

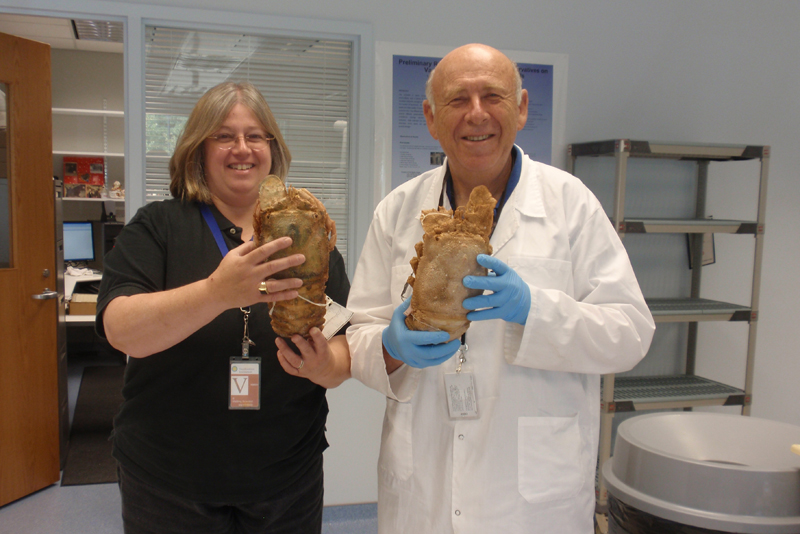

Kari Lavalli is studying the impact of overfishing and climate change on lobsters, including a recent decline in the number of young American lobsters in southern New England waters. Courtesy of Kari Lavalli

It sounds like a seafood diner’s dream, or maybe nightmare: lobsters four feet long or even bigger, and so abundant that you could just reach over the side of the boat and grab them. That’s what it was like in the waters of southern New England four centuries ago, according to historical accounts, says Kari Lavalli (GRS’92), a biologist studying the declining size—and health—of the lobster population.

Lavalli, a senior lecturer at Boston University College of General Studies, hopes that what she’s learned about lobsters then might help us protect them now. She’s studying the impact of overfishing and climate change on lobsters, including a recent decline in the number of young American lobsters, Homarus americanus, in southern New England waters, a drop that could have a major effect on regional economies and menus.

The Incredible Shrinking Lobsters

Today’s lobsters are much more cooking pot–friendly than their ancestors: a modern, mature New England lobster is usually only 8 to 24 inches long. To uncover the history of their contracting size, Lavalli spent much of 2017 on a “treasure hunt” for written accounts of the lobster population from the 1500s through the early 1700s. In most cases, European explorers and colonists in the New World wrote these accounts, which also charted how the crustaceans were eaten and used by Native Americans, in letters back to their homelands.

“A lot of their letters talk about how big our lobsters were,” says Lavalli, who intends to write a small book on Native Americans and lobster, based on her research. According to these accounts, four-foot or even bigger lobsters were common in New England. That would mean lobsters of more than 25 pounds. “And they talk about how they could just gaff these animals right off the sides of their boats and pull them up, and within an hour they could get enough to feed 400 people,” Lavalli says.

In Native American communities, women and children harvested lobsters every fall, then “they would smoke them, to make a kind of jerky. The Europeans remarked that the jerky tasted awful to them,” Lavalli says. They preferred boiled lobster as an appetizer for a multicourse meal, and one settler describes a pilgrim community plunged into embarrassment when they had to serve lobster as the main course, because it was all they had.

Native Americans let no part of the lobster go to waste. They “would throw the shells on their fields where they were growing maize or other things, as fertilizer,” Lavalli says. “If they had big claws they would turn them into pipes. There’s one account by a European who was amazed how big the pipe was and how much tobacco it held.”

The Europeans were not exaggerating. Lavalli spoke with a curator at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center in Mashantucket, Conn., whose archaeological dig in a 2,500-year-old “midden”—basically a Native American landfill—on Block Island, R.I., has uncovered large lobster mandibles, shell segments from the lobster’s jaw. From the mandibles, she hopes to verify those European accounts of lobster size.

Lobster shells are rarely preserved for long, as their calcium carbonate structure is not as strong as bone and generally dissolves over centuries, especially if left on an open field. But some, like those on Block Island, do withstand the assaults of time and contribute to a global picture of lobster shrinkage. “They found mandibles in caves in South Africa, and they’ve got them dated to 10,000 years ago, and they’re huge, compared to what you see in populations today,” says Lavalli. “Mandibles scale to the size of the animal, just like your hand scales to your size. If you see a decline in the size of mandibles, it indicates a decline in the size of the animals, which indicates overexploitation of the resource by predators.”

Human predators have historically targeted the largest (most mature) lobsters, and as we chipped away at their population, we put stress on lobsters to reproduce. Females began to sexually mature earlier (and at proportionally smaller sizes), scaling down the entire population. This trend indicates to fishery managers that we are overexploiting the species; experts are considering solutions that include putting a moratorium on fisheries, decreasing the number of lobster traps, and increasing the minimum size of fished lobsters to allow the population longer to mature. The bigger the lobster, the more eggs she can carry.

Not Just Shrinking, Getting Sicker

Overexploitation isn’t the only threat to lobsters that Lavalli charts. She’s also helping catalogue the impact of the warming climate on contemporary lobster populations.

“If you go out and sample the surface of the water to catch the lobster larvae, we’re not seeing any big changes in the number of first-, second-, or third-stage larvae,” Lavalli says. “There seem to be plenty out there, not any different from previous years or decades. But we’re seeing a reduction in the number of post-larvae, and in southern New England we’re seeing no post-larvae.” In a few years, that would mean fewer lobster larvae transforming into fully fledged lobsters. Catches have already sunk precipitously in southern New England. Connecticut, for example, hauled in more than 3.7 million pounds in 1998, and was down to less than 260,000 pounds in 2016, according to National Marine Fisheries Service data.

One culprit: climate change. “Climate change affects lobsters in a multitude of ways,” says Lavalli, who cochaired the 11th International Conference and Workshop on Lobster Biology and Management in Portland, Maine, in June 2017. Warming in-shore waters bring new predators and parasites, as do increasing ocean acidification and changes in plankton population. Warmer waters are also spreading a shell disease as far as southern Maine that can cause lesions in the shell, weakening those lobsters that do escape the larval stage and disrupting natural molting and reproductive cycles in female lobsters, as well as making the lobsters unsuitable for the retail market because of their appearance. The coastal seas losing their chill has yet another impact, driving lobsters to colder and deeper waters; in-shore fishermen may not have licenses for federal waters farther offshore, meaning their previous catch would be off-limits.

Lavalli says lobsters are an ancient species and have seen many instances of climate change over their history dating back into the Cretaceous. It is likely they have a number of tricks to deal with warming waters, but we have yet to learn what these are.

She’s looking to one species, the slipper lobster, for clues. The slipper lobster, which lives in warm waters like those of Hawaii and the Pacific Ocean, has a flat body, shovel-like antennae, and a slightly thicker shell that makes it less vulnerable to predators than New England lobsters. The slipper lobster is also immune to the shell disease plaguing its New England counterparts. Lavalli is asking: “Why don’t slipper lobsters get shell disease, even though they typically live in very warm waters?”

In search of answers, she’s testing the biochemical properties of the slipper lobster’s shell and the fluoride content of their waters. However slipper lobsters avoid shell disease, Lavalli says the big takeaway is that “they evolved to deal with these warmer temperatures and higher bacterial activities. And you have to ask: Would clawed lobsters ever be able to do that in the time period we’re giving them to do it, because we’re not giving them a lot of time. As we humans change the environment, we’re not giving any species a lot of time to cope with the changes that are occurring.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.