The Process of Business Innovation

How to use a strategic approach to creative thinking

It’s the secret everybody wants to know: how do you come up with that killer idea? When will that flash of inspiration come that turns you into the next Steve Jobs, the next Mark Zuckerberg? Every business, every entrepreneur, is desperately waiting for a shout of “Eureka!” in the tub—and record profits.

The truth is, innovation is more than a moment of genius; it’s a process through which that idea becomes a value-creating product. Take tax software company Intuit. In 2011, Intuit announced the national rollout of a breakthrough app that allowed users to file their taxes by smartphone. It wasn’t the brainchild of any single employee, but a team of experts from across the company. Intuit had started out looking for a way to help customers scan tax documents, but when its software and tax experts watched customers using their phones, they realized they didn’t have to stop at a glorified camera app. With prototyping, constant iteration, and field testing, they created the SnapTax app in just six weeks. It allowed users to file simple tax returns in about 15 minutes; within two weeks of its launch, SnapTax had knocked Angry Birds off the top of the iTunes app chart, according to Intuit’s CEO.

“There’s nothing routine about the innovation journey,” says Siobhan O’Mahony, a Boston University Questrom School of Business associate professor of strategy and innovation and a dean’s research fellow. “Most of the time, businesses are focused on replicating processes they’ve worked out that deliver great value in terms of products and services. We can teach people to operate more efficiently, we can teach them to operate more effectively, and we can give pretty precise prescriptions about how to improve along metrics that are already known and identified. But when we innovate, we break away from routine.”

She studies how companies and groups organize for innovation—that is, how they create environments that allow ingenuity to thrive while supporting institutional goals. Her research offers insights to both new and established firms about where innovative ideas come from and how we can transform those ideas into sources of value.

O’Mahony explores how organizations bridge the gap between the fluid, often unpredictable art of creativity and the refining and evaluating that are necessary to bring an amorphous idea to reality. “When we look at innovation, we see a replicable process, but it doesn’t look like you’d expect it to,” she says of her work. “It’s a dance between generating and cultivating—between letting a thousand flowers bloom and reining it back in.”

Identifying the replicable aspects of successful innovation drives O’Mahony’s research. Her findings have given rise to a number of best practices applicable across fields for all stages of the innovation process, from idea to product to marketplace.

Where do good ideas come from?

At the heart of innovation, of course, is an idea. But the innovation process actually begins before the idea, with two questions: why are we seeking to innovate in the first place? What is the need our organization seeks to meet?

“For the individual who wants to be more innovative, the first step is getting the problem right,” O’Mahony says. “The better you understand your problem, the better your solution is going to be.” This is one reason the best ideas tend to come from the people who are closest to the consumer or to the products: a comprehensive understanding of customers’ habits or the strengths and weaknesses of a product can lead us to identify a previously unmet need—the vital innovation practice known as “need-finding.” This is the breakthrough that renders superfluous the product or technology that our innovation replaces. A commercial airline pilot answered an unmet need among his colleagues by putting two wheels and a collapsible handle on a suitcase, and in so doing upended the luggage market. “Identifying the unmet need is the holy grail for innovation. Once that innovation is created, everybody’s suitcase under their bed and in their closet has no value,” O’Mahony says.

Need-finding requires “deep observation of human behavior,” O’Mahony says. Deep observation happens when you see your flight crew exhausted from lugging their bags from gate to gate. It happens when you’re at a party and the host is struggling to answer late guests’ texts by typing on a phone docked to her speakers—you realize that she needs the phone to be in her pocket, and you create the Bluetooth speaker. “Those deep insights of unmet need really come from taking stock of the behaviors and experiences around you and not trying to change them, but trying to design to them,” O’Mahony says.

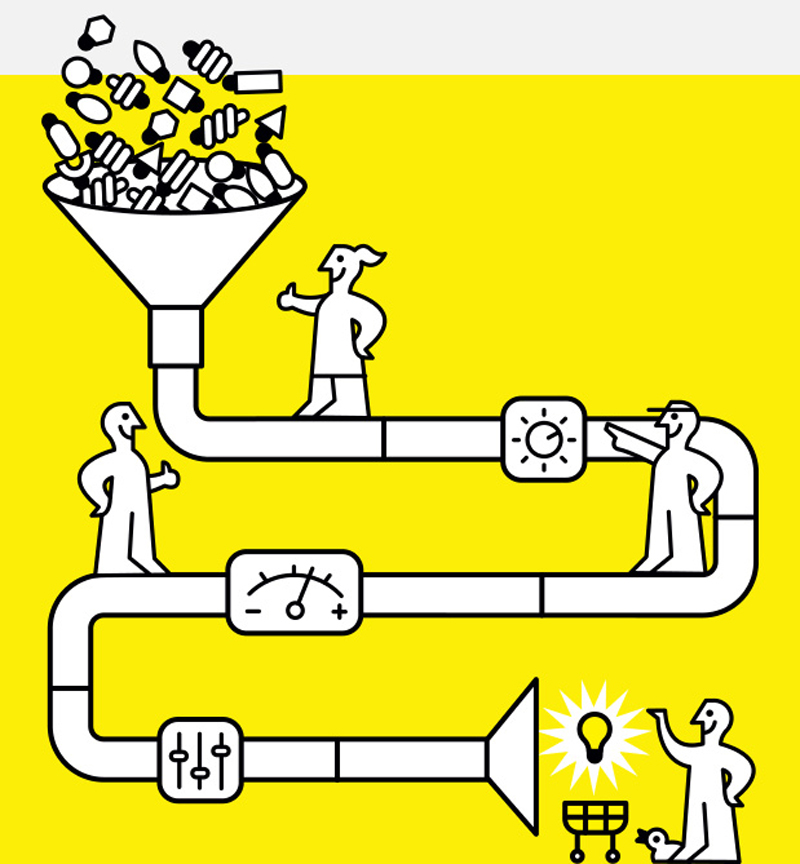

Once a need is identified, the next step is to find a solution. This is the stage of a thousand ideas blooming. The more ideas—more numerous, more radical, more diverse—the better. O’Mahony uses the metaphor of a funnel. At the top of the funnel are the raw materials of innovation: the crazy notion, the surprising insight, the Hey, what if we tried this? “Most ideas will fail, and that’s okay,” she says. “That’s how the innovation process works. You take the ideas from the top of the funnel and iterate and refine them so that what comes out at the bottom is an innovation.”

Most great innovations aren’t completely fresh themselves, but originate as new combinations of things that already exist—Airbnb and Uber, for example, innovated by putting the renting of hotel rooms and hired cars into a new context. Encouraging lots of ideas from a broad range of people increases the chances of landing on one of these new combinations. According to an innovation theory known as the variance hypothesis, exposure to a wider range of ideas from different fields outside our usual frame of reference increases the capacity to innovate, and it applies at all levels of an organization. Teams that bring together people with diverse areas of expertise, experience, and perspective produce more, and more innovative ideas. The same goes for firms that look outside institutional walls—creating cross-industry partnerships or crowdsourcing.

But O’Mahony has found that the innovative value of our network is only as great as the quality of our contacts. In “One foot in, one foot out: How does individuals’ external search breadth affect innovation outcomes?” published in 2014 in the Strategic Management Journal, O’Mahony and her collaborators looked at innovation among the top engineers and scientists at IBM, one of the world’s largest holders of intellectual property. As the variance hypothesis predicts, the most successful innovators had broad, diverse networks that ranged across institutional and vocational boundaries—customers, suppliers, members of government, academics, competitors, and members of trade associations.

But O’Mahony also found that the innovators with the most impact were those who allocated more time to developing the individual contacts within their networks. The researchers with “thick” ties—those more intimate connections cultivated through meetings, site visits, and other in-person interactions—produced not only more ideas but more novel and useful innovations than those whose networks consisted of less robust ties, however diverse those networks may have been.

“After you’ve got the problem right, the second step for those who want to be more innovative is to get out of your chair and engage with the world,” O’Mahony says. “Talk to as many people as you can. And not just by email; I really believe context matters. Engage in real dialogue—in person, on site.”

Turning an idea into reality

Most innovations need time and space to evolve, and developing an initial idea into a successful product is a social process—team members work together, each raising questions and contributing solutions along the way. That’s what happened at Intuit with the SnapTax app. As MIT Technology Review put it in a 2011 article on the company’s product design process, “Regular employees were trained as ‘innovation catalysts’ who worked with teams on better strategies for assessing what customers wanted and coming up with ideas for how to provide it.”

Teams working on turning an idea into a product face a challenge unique to this process: how do we share a concept of a thing that doesn’t yet exist? “One of the things that matters to innovation is making sure that everyone who’s working on the product is touching the same elephant,” O’Mahony says. In a 2014 article for the journal Organization Science, “Managing the Repertoire: Stories, Metaphors, Prototypes, and Concept Coherence in Product Innovation,” O’Mahony and Victor P. Seidel of Babson College studied six product development teams as they created new tech devices, medical technologies, and automotive products. As each product was designed, the original concept needed to be continually reconsidered, refined, and redefined. Every day brought new decisions to be made, new questions to be answered. O’Mahony and Seidel looked at how team members made these decisions.

They found that successful innovating teams used three kinds of verbal and visual representations to communicate and maintain a consistent, coherent vision of their product. The teams used prototypes to communicate the product’s physical appearance. They also used stories that captured the essence of the problem to be solved by the product. For example, an anecdote about a company founder unable to carry all of the books and paperwork he needed on a transcontinental flight was the focal narrative for a team creating an e-book reader in a pre-Kindle era. The story encapsulated a central need the e-reader would fill and provided a reference point for designers: it had to be portable and able to handle a variety of content. Questions of device size, battery life, memory capacity, and user interface could be answered in the context of a user on a long flight.

Successful innovation teams also used metaphors or slogans to communicate key qualities of a product. For the e-reader team, the phrase “It’s not a computer, it’s a book!” became a touchstone to keep team members on the same digital page as they faced the daily decisions involved in creating their new product. Would content be displayed in a long block of text, via scrolling, or would it be formatted as individual “pages”? Designers chose the latter, to keep in line with the book metaphor. Would the device include a calculator? No, because books don’t have calculators.

The prototype, the story, and the metaphor function together as a “repertoire of representations,” says O’Mahony, to create a specific, shared vision of what the product will be.

But the process of bringing an innovation from idea to reality is a complicated one. Every step of the developmental process is affected by many factors, such as limitations around cost, feasibility, technical capabilities, and market demand.

O’Mahony and her colleagues identified a set of best practices to ensure that the collective vision evolves in response to these inevitable limitations. First, be clear about constraints. The idea-generating phase is the “more is better” part of the innovation process; now it’s time to rein things in. When everyone working on a team has their own idea for the grand possibilities of a product, consistency and coherence suffer. A metaphor like “It’s not a computer, it’s a book!” defines the scope of the product and provides a context for making design decisions.

Second, get rid of models that don’t work. If a slogan no longer captures the essence of the product, discard it. That handsome initial prototype showcasing an early, idealized version of the product? If it’s no longer an accurate representation of the product, replace it with a more realistic model.

Finally, as new prototypes, stories, or metaphors are created to replace outdated ones, give team members opportunities to ask questions and voice their opinions. Make sure disparities among individuals’ ideas about the product are addressed and resolved so that everybody is working from the same concepts, even as the product evolves.

Measuring success

Business leaders who seek to build companies that can respond to creative ideas face a challenge: innovation involves working with, and trying to predict the value of, something entirely new. While looking at the sales of new products or the number of patents can give us a sense of whether our innovation program is working, it can’t tell us about how it’s working—or help us find what isn’t working. Instead, O’Mahony says, we need to consider the health of the entire innovation process. “Any measurement that just focuses on output and outcomes is a mistake,” she says. “It’s very hard to improve the hit rate of any idea, no matter what it is, when it comes out at the bottom of that funnel. So, it’s important to have high-quality input. We need to look at the flow of ideas: How diverse is the sourcing of ideas? Who are the people getting funded, and who isn’t getting funded? How well do these ideas get advanced?”

Leadership needs to think critically not only about the sourcing and diversity of ideas being generated, but about how we select which ideas to move ahead and which to jettison. The key: don’t be too hasty. If we act too quickly to cut our losses, we risk missing out on promising innovations. We may not immediately see the market for a new idea; we may misjudge its potential value; we may see only the obstacles to an idea’s success and not the path that allows it to thrive. “I see so many companies that prematurely kill an idea, only to find a competitor launches that product within six months or a year,” O’Mahony says. “There is a gestation process to innovation. You have to let the little seedlings grow. Too many companies dump them out of the pot before they’re ready.”

To nourish the seeds of innovation, she says, we need to create “slack”—to free up resources, to make space for new ideas to gestate. That may mean giving time to employees to work on their own ventures, as 3M has done since its 15 percent program, which allows researchers to spend up to 15 percent of their paid time on projects of their choosing, was launched in 1948. It may mean allocating funding and resources, as JPMorgan Chase & Co. has done in establishing an in-house incubator for financial startups, offering entrepreneurs access to its knowledge and systems to support the innovation of technology solutions to industry problems. It may mean giving an idea to another team, doing deep field research, looking for other data, or simply leaving an idea on a back burner to simmer until a path forward becomes clearer. “You’ve got to create your sandbox,” O’Mahony says. “You need to create room to experiment, to allow new ideas to incubate and evolve and iterate and process. Whether it’s money or space or time, you need to create the slack resources—in the name of the future.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.