The Preservationist

For Daniel Bluestone, it's about connecting people and places

Daniel Bluestone, a specialist in 19th-century American architecture and urbanism, is the director of BU’s Preservation Studies program. Photo by Cydney Scott

Looking across the Charles River Campus, it can be hard to see much in the way of history. The George Sherman Union, StuVi I and II, the Photonics Center, and the Yawkey Center come to mind. Even the Gothic arches of Marsh Chapel date only to 1949. But spend an hour with Daniel Bluestone, the new director of BU’s Preservation Studies program and you begin to see things differently.

“BU has preservation in its DNA in a way that many urban universities do not,” says Bluestone, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of history of art and architecture. “Most urban universities are so predatory in relation to the environment that they occupy. But BU has this very different attitude, which is: let’s figure out how to use these buildings and keep them going, get another 100 years of use out of them and have them become part of our mission.”

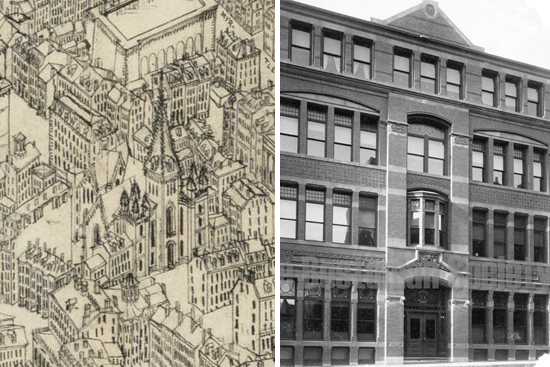

He says that commitment to preservation can be traced to 1882, when BU bought the First Baptist Church on Somerset Street near the top of Beacon Hill, removed the steeple, and adapted the building to become the home of the University’s administrative offices and the College of Liberal Arts. Thus began a long history of respecting and reusing buildings rather than tearing them down.

Bluestone says that the townhouses seen from his office on Bay State Road, an area that’s now a historic district, are another example of BU’s determination to find new uses for old buildings. He also cites the current rehab of the School of Law tower as further evidence of that commitment to preservation, pointing out that when the tower was built in the 1960s, Boston’s future was uncertain. “No one knew whether Boston was going to, through decentralization or suburbanization, crash and burn,” says Bluestone. “The fate of Boston was of real concern to BU, and they built this building to be the first skyscraper one would see coming along the new Storrow Drive or the new extension of the Massachusetts Turnpike. It demonstrated a tremendous optimism in the city.”

He says the renovation of the building, and the addition of another 95,000 square feet at its base with the new Sumner M. Redstone Building, is BU saying, “We can figure out a way to live with our historic buildings and make them useful, but we’re not going to be so curatorial that we’re unwilling to touch them.” According to Bluestone: “It’s the healthiest possible attitude.”

After 20 years at the University of Virginia, where he earned a reputation as one of the nation’s top preservation educators and advocates, Bluestone came to BU last August. By his own count, he’s been involved in at least 30 projects that have resulted in buildings and neighborhoods being successfully nominated to the National Register of Historic Places, and he has served as a consultant on preservation projects as far away as China and Iraq.

He is the author of two well-known books on preservation—his Buildings, Landscapes, and Memory: Case Studies in Historic Preservation (W.W. Norton, 2011) received the Society of Architectural Historians 2013 Antoinette Forrester Downing Book Award. His appointment at BU is a significant development for the Preservation Studies program, founded in 1983 under the auspices of the American and New England Studies Program.

“We are in a unique position here in Boston to stimulate an important discussion—with students, faculty, and the broader community—about preservation, and Daniel is absolutely the right person to get this going,” says Nina Silber, American and New England Studies Program director and a CAS professor of history. “He looks at preservation not as the narrowly aesthetic study of window frames and doorknobs, but as a deeper exploration about place: what place means for the people who live and work there and the values they attach to those places.”

Tightening the connection between people and places

Growing up in Roxbury and Newton Centre, Bluestone was drawn to cities even as a child. “I loved traveling to unfamiliar places and exploring them,” he says. Later, as an undergraduate at Harvard, he participated in a few architecture and urban projects, but his interest in preservation began in earnest when he started working for the Historic American Engineering Record, which was part of the National Parks Service. He spent a summer touring steel mills and industrial plants along the Cuyahoga River in Ohio, looking for historic engineering structures. He discovered several huge industrial machines called Hulett ore unloaders that had been used to remove iron ore from ships and deposit it into waiting train cars. By the time he arrived in Ohio, those huge machines were obsolete, but he advocated for their preservation, saving a symbol of Cleveland’s industrial heritage. He went on to earn a PhD at the University of Chicago’s Committee on the History of Culture.

“I love old buildings, but I also love old buildings’ ability to get us to think about the world that we live in,” Bluestone says. Understanding the ways cities and buildings are put together increases a person’s connection to a particular place. “That enriches people’s lives tremendously. One of the important things we do in historic preservation is to figure out how to tighten the connections between people and places and people and each other.”

By way of example, he cites an ambitious project to preserve Chicago’s bungalows. At one time, it would have been unthinkable that these humble single-family dwellings were worth a major preservation effort. Chicago was famous for buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, and Louis Sullivan, not for working-class residences. But a push by Mayor Richard Daley, Jr., to restore the city’s bungalows, preserve their architecture, and retrofit them to be energy-efficient, drew Bluestone’s attention. He and some of his students began researching bungalows in three specific districts, painstakingly documenting the history of the houses from original building permits and census records.

“We wanted to start developing a historical narrative so that instead of looking down on these bungalows, people would look at them proudly and understand their history and the communities they were part of, ” he says. “You could see social capital being formed right there, right then, as people understood something about their house, their neighborhood, their community.”

Bluestone’s favorite project involved a plantation called Belmead, on the banks of the James River in Powhatan County, Va. Built by one of the South’s largest slaveholders, the site was later acquired by American heiress Katharine Drexel, who became a nun and established the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament. (Drexel was canonized in 2000). Her order was charged with educating African American and Native American children, and she saw the symbolism in turning the site into schools. “She understood she could take a site where African Americans had been held in slavery and turn it into a site where they’d be given an education and the confidence to own property instead of being owned as property,” Bluestone says. The schools continued to operate until the early 1970s. When they closed, a small group of nuns remained behind, desperate to preserve the site. He and some of his UVA students spent a year collaborating with a modern architect, convincing the order to preserve the property.

As he dug deeper into the project, Bluestone became interested in understanding how the land had been cultivated during its plantation years and the implication of the main house’s Gothic revival architecture, which was a repudiation of the Southern plantation house. “I think we gave people a sense of the significance of the entire site,” he says.

Why BU?

Bluestone points to the excellent reputation of BU’s Preservation Studies as one of the reasons he decided to leave UVA to return to Boston. “It’s very rich to work in a UNESCO World Heritage site, which is what the University of Virginia is,” he says, “but I think it’s potentially even richer to work in a site that has a much more varied and dynamic preservation portfolio, because you’re dealing with an entire city and region.” Boston has a vital connection to preservation and thus offers “an excellent place to teach students,” he says. He also indicates the program’s ability to draw on a “deep bench” of faculty in history, architectural history, American and New England studies, archaeology, and urban planning.

He has big ambitions for the program. Next September, the curriculum is offering students the opportunity to spend an entire semester delving into one particular community. Bluestone says he and his students will “turn loose on a single place, a single neighborhood and really look at the meaning of that place, how it developed historically, what its architecture represents, and who the people are who have lived there,” in order to deeply understand “a patch of the city.” He hopes that this won’t be just an academic exercise, but that students will produce guidebooks and exhibitions and guided tours, taking their academic understanding of a place and using it to make the place popular and available to the public. He also hopes the work will inspire residents of other neighborhoods to do the same. He is consulting with colleagues at the Massachusetts Historical Commission and the Boston Landmarks Commission to help identify a site that needs the attention and would appreciate their help.

Bluestone also hopes the Preservation Studies program will attract more students who are pursuing other degrees, be it history, art history, archaeology, or urban planning. For example, he says, “there will be students studying planning in Metropolitan College. They might not be doing a degree in preservation, but having the insight from preservation courses will enrich their education, their understanding of how the world of planning works and how preservation constitutes an important resource in building community and building neighborhoods and rehabilitating spaces.”

For this spring semester he devised and helped teach an undergraduate cross-disciplinary course titled What’s Boston? The course explored the city’s society, culture, environment, and economy, drawing on faculty from anthropology, earth and environment, history of art and architecture, the Schools of Law and Medicine, and elsewhere. The goal, says Bluestone, was “to put the Boston in Boston University” by helping students form intense bonds with the city they call home. It was also designed to give undergraduates a better sense of what preservation studies is all about.

Historic preservation is more significant now than ever, he says, because it’s the keystone to sustainability. “The most sustainable thing you can do is to figure out how to get extra years out of buildings that already exist—not to tear them down, but to renovate them and continue to use them.

“Preservation has the ability to get people to think critically about the world they live in by thinking historically,” Bluestone says. “You can think critically about the past in order to inform the way you are a citizen today and in the future.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.