The Climate Crisis: Your Job or Your Planet?

Research says action on climate change won’t stifle economy

In this weeklong series, BU researchers explore the science behind Earth’s environmental changes, and what they mean for our future.

For a glimpse of a ferocious front in our war over climate change, poke your head in the University’s next Career Expo. Every semester, scores of students flock to meet employers visiting campus to discuss jobs or internships. What do these jobs fairs have to do with climate change? Everything, some environmentalists say.

Jobs put money in people’s pockets. People will spend that money, and in turn feed a demand for goods that deplete resources and whose production results in pollutants. The economy thrives, but the planet roasts, as we demand more stuff and services.

Growth, argues an advocate of measuring “Gross National Happiness” in a recent New York Times forum, “is a misleading indicator of well-being. The real goal is happiness and well-being and all those things that they represent, like vitality and health, social empathetic relations, pure and vibrant nature, and meaning and freedom.” Elsewhere, author and climate change crusader Bill McKibben says we must stop focusing on growth and instead encourage locally based agriculture and economics, adding that rich nations have an obligation to help poor ones develop such systems.

Job-seeking students could be forgiven for asking if the next generation should be expected to sacrifice in order to save the planet, enduring an even dicier hunt for work than they do now.

Ian Sue Wing, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of earth and environment, has one piece of advice: relax. “Human beings will continue to aspire to higher standards of well-being, and government will continue to put in place policies to stimulate growth,” says Sue Wing, who researches the economic costs and consequences of both climate change and efforts to halt it. “If we were able to switch to non–fossil fuel sources of energy,” replacing oil and coal with wind, solar, biomass, and/or nuclear power, “we could pursue economic growth without altering the atmosphere and the climate at anywhere near the rate we are doing now.”

One BU economist agrees. “Most estimates for the economic impact of strategies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions have relatively moderate impacts” on growth, says Johannes Schmieder, a CAS assistant professor of economics. Schmieder, who teaches environmental economics, says that by addressing climate change, “we might reach the level of gross domestic product that we would have reached in 2050…in 2051 or 2052 instead.”

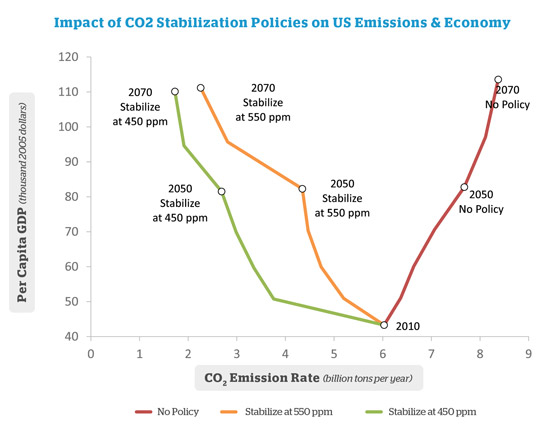

Sue Wing bases his views on his computer modeling of economic growth to 2070, with and without a policy to ease climate change by imposing a tax on carbon dioxide emissions. The model shows that even with companies and households paying the tax, “the economy will continue to expand, but at a slightly slower pace than in the no-policy scenario,” Sue Wing writes in a summation of unpublished, ongoing research. “Equally important, taxes aren’t a net loss to the economy, as tax revenue finances the government’s provision of services that are economically and socially valuable.

“The upshot is that from the perspective of the entire society, the real cost of abatement isn’t firms’ and households’ tax payments on the CO2 they emit—rather, it is their opportunity cost of diverting resources toward cutting emissions below their no-policy levels, which results in a smaller quantity of goods and services being produced and consumed.”

Sue Wing’s earlier research confines itself to the economic cost of easing climate change. He is currently researching the economic cost of failing to ease global warming and its effects on such industries as farming.

The good news is that a world with cooler temperatures can still churn out jobs comes with two reality checks, however. One is that while fighting climate change would shave only a few percentage points off growth in the next few decades, Schmieder notes that we’d have to bear those costs now, while the benefits would come in the murky future. We humans aren’t great at deferring satisfaction, yet Schmieder thinks it’s doable. “We have seen large efforts for future payoffs in the past,” he says, citing the race to the moon. “I don’t see why politicians couldn’t create an atmosphere like that again, where it becomes a matter of national pride to solve our global climate problems.”

The second reality check is that some climate change is already baked in to our future. “If we were to stop emitting all CO2 on a global basis tomorrow, then it would still take on the order of 100 years for the current warming trends to essentially cease,” according to Richard Murray, a CAS earth and environment professor, who researches climate cycles over multiple time spans. Sue Wing says that the environmentally benign energy production he dreams of is still decades away, for technological and economic reasons.

In short, we must adapt to some climate change, and rather than stop it, we must mitigate it. One immediate and necessary strategy will create jobs, Murray says: switching to environmentally benign ways of doing everyday things like home construction, where you can already see baby steps toward the future. Some Massachusetts towns demand tighter reviews of proposed resource-gobbling McMansions. And a California firm is offering low-mortgage micro-dwellings, some comically tiny.

Longer term, our experts say we need new energy sources and technologies that capture carbon dioxide from industrial processes before it gets into the atmosphere. None of these changes will make it harder for BU grads to find work, they say. “But they have to be going after the right jobs” in what will be a greener economy, says Murray. And he says that’s something students have always done as industries die and new ones appear: “I wouldn’t encourage BU engineers to develop a better technique to cut ice blocks from frozen ponds for us to use in our iceboxes.”

Bottom line: if you were planning to hit that next Career Expo, go.

Related Stories

This Series

Also in

The Climate Crisis

-

March 25, 2013

The Climate Crisis: Why the Earth Is Warming

-

March 26, 2013

The Climate Crisis: Tracking Change, Predicting Trouble

-

March 27, 2013

The Climate Crisis: Measuring Boston’s Metabolism

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.