Machiavelli’s The Prince: Still Relevant after All These Years

Historians consider book’s five-century legacy tonight

In a recent interview with the New York Times, Pulitzer Prize–winning author Jared Diamond was asked which book he would require President Obama to read if he could. His answer? Niccoló Machiavelli’s The Prince, written 500 years ago.

His explanation was that while Machiavelli “is frequently dismissed today as an amoral cynic who supposedly considered the end to justify the means,” he is, in fact, “a crystal-clear realist who understands the limits and uses of power.” Diamond, whose books include Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies, said that what continues to make The Prince compelling reading for today’s political leaders is Machiavelli’s insistence “that we are not helpless at the hands of bad luck.”

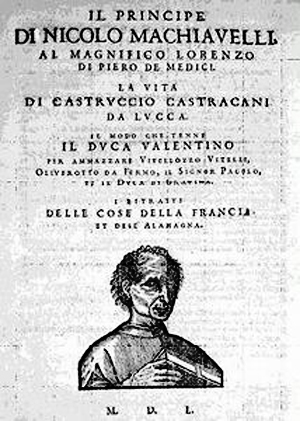

The slender political treatise is one of the most influential and controversial books published in Western literature. Critics have long debated whether The Prince, which famously argues that the ends—no matter how immoral—justify the means for preserving political authority, was written as a satire, or as British philosopher and Nobel laureate Bertrand Russell once said, as “a handbook for gangsters.” While Machiavelli’s intent is unknown, this much is indisputable: the book continues to be a searing meditation on the means some people use to get and maintain power.

Among the precepts espoused by Machiavelli: leaders should always mask their true intentions, avoid inconsistency, and frequently “act against mercy, against faith, against humanity, against frankness, against religion, in order to preserve the state.” His name has become synonymous with cunning tyrants.

To celebrate the book’s 500th anniversary (it was written in 1513, but not published until 1532, five years after the author’s death), the College of Arts & Sciences history department is hosting a special event, Machiavelli’s The Prince after 500 Years, at 7 p.m. tonight in the Photonics Center. It is free and open to the public.

The panelists are Canadian scholar and politician Michael Ignatieff, who as leader of the Liberal Party of Canada was leader of the opposition from 2008 to 2011 and now teaches at Harvard and the University of Toronto; Edward Muir, a Northwestern University history professor, who has written widely about the Renaissance; and James Johnson (right), a CAS associate professor of history and author of two prize-winning books, Listening in Paris: A Cultural History and Venice Incognito: Masks in the Serene Republic.

BU Today spoke with Johnson, recipient of a 1996 Metcalf Award for Excellence in Teaching and former CAS assistant dean and director of the Core Curriculum, about why Machiavelli’s masterwork continues to resonate.

BU Today: What was Machiavelli’s intent in writing The Prince?

Johnson: That is one of the great unknowable questions. Some say he wanted to empower tyrants; others say he listed their crimes the better to expose them. Readers across the ages have found support for all kinds of causes: monarchists, defenders of republics, cynics, idealists, religious zealots, religious skeptics. Whatever its intent, one thing is clear. The book follows its declared purpose fearlessly and without hesitation: to show rulers how to survive in the world as it is and not as it should be.

Was he arguing that the ends justify the means, or is that assessment too simple?

Machiavelli is famous, or infamous, for shifting the sense of “virtue” from moral worth to effectiveness. The virtuous figures of The Prince are those who do whatever it takes to seize and maintain foreign territory, even if it entails the grossest violations. This is a morality, if that’s the right word, of ends. Now, was Machiavelli arguing for this or merely offering his prince a value-neutral how-to manual for rule? That’s a question the book doesn’t answer.

Some have described the book as a political satire. Do you agree?

I don’t. From all I can tell, it was offered sincerely to Lorenzo de’ Medici as a kind of job application. But I do like the idea. Maybe we should invite Jon Stewart to stage a dramatic reading with his full repertoire of winks, shrugs, grimaces, and paper-shuffling.

How would you describe the book’s impact?

This is a book that asserts many shocking things as simple precepts. When you injure someone, do it in a way so that he cannot take revenge. Cultivate an enemy so you can intimidate others by crushing them publicly. It is natural and normal to take territories that do not belong to you. Does Machiavelli, therefore, share some blame for the violence and brutality that has wracked the globe since he first wrote? No. People don’t need The Prince to be inspired to commit every atrocity it names and more. The impact of the book has instead been to force countless readers over the past 500 years to confront, in the starkest terms possible, the most important questions about politics and morality.

You’ve taught the book for years. What continues to surprise you?

Its tone, which is wickedly simple. In the dedication, Machiavelli says he has not embellished his book with “pretentious and magnificent words.” That’s true, but he does other things in the writing to which he draws no attention. Some of his most objectionable recommendations are put in ways that make them sound eminently reasonable. “In order to get a secure hold on new territories,” the book advises, “one need merely eliminate the surviving members of the family of their previous rulers.” How innocent-sounding is that “merely.”

How do your students respond to The Prince?

A number of years ago, one excellent student, now a professor at a private East Coast college, objected time and again to the “lies” that filled the book. As she left class that day, she tossed the book in the trash can for dramatic effect. Another student claimed that the New Jersey congressman for whom he interned kept a copy of The Prince in his desk. Most students now claim that they find nothing surprising or shocking in the book, and I have to work hard to stir outrage.

How do you do that?

I ask them to imagine an advisor to Slobodan Milosevic, the nationalist president of Serbia during the Balkan wars of the 1990s, presenting plans for annexing parts of Bosnia to the leader. The advisor says, “I’m not recommending you do this—and I’m not saying it’s right or wrong—but if you want to succeed, here’s what you must do.” The advisor goes on to detail the means of ethnic cleansing: political assassinations, mass deportation, the summary execution of boys and old men, and the systematic rape of women. I ask the students, “If Milosevic has his advisor’s strategy in mind when he gives his orders, is the advisor morally implicated in what follows?”

And what is the response?

A very thoughtful discussion. Students now see the troubling questions this book raises.

Machiavelli’s book was considered groundbreaking when it was first published. Why?

The Prince was one of a long line of advice books for rulers, a genre called the “mirror-for-princes.” They framed their instruction—which included eloquence, history, geography, music, and dance—according to principles of Christian virtue. Machiavelli stripped the language of ideals from the genre, omitted the ornamental qualities of personal style and polish, and drew examples from history. He wrote that anyone who ignores reality in order to live up to an ideal will discover that he has been taught how to destroy himself.

How has the book been reinterpreted over the centuries?

Cardinal Reginald Pole, the English prelate, wrote in 1539 that The Prince was written “by Satan’s hand.” In the 18th century, Rousseau wrote that in the guise of advising princes, Machiavelli was in fact instructing the people how to secure a republic. Some postwar interpreters have written that he should be grouped with the Nazi party. Each age—each reader—fashions in some degree its own Prince appropriate to its own experience.

How much has the political behavior Machiavelli described changed and how much remains the same?

The awareness of, and public outcry over, state violence and its horrific human costs are much greater today than they were in Machiavelli’s day. As a consequence, we might also say that the response of the international community to such violations—expressed through organizations like the United Nations and the International Court of Justice—is more immediate and in some cases more effective. I wish I could say that humanity has grown more peaceful, but I don’t believe it is true. Perhaps rulers have become better at justifying war since Machiavelli’s day. He would not have been surprised.

What do you think Machiavelli would make of contemporary American politics?

He would smile that famous inscrutable smile of his, as if to say, “This looks familiar.”

Machiavelli’s The Prince after 500 Years, sponsored by the CAS history department, is tonight, Wednesday, February 6, at 7 p.m. in the Photonics Center, Room 206, 8 St. Mary’s St. The event is free and open to the public.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.