Dreaming of Jazz

Cinematheque: COM prof's Jazz Dreams II screens tonight

In 1998 Geoffrey Poister was living in New Orleans and looking for his next documentary subject when the idea of following several young jazz musicians struggling to launch their careers came to him. Poister had been influenced by Michael Apted’s classic 7-Up series and Hoop Dreams—documentaries famous for following the trajectory of young people as they grow up and struggle to find success—and he wanted to do the same.

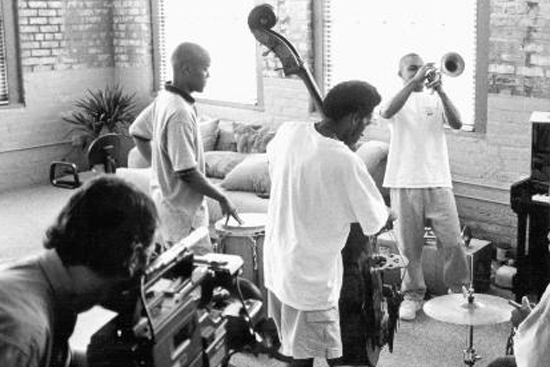

Poister chose three young musicians: jazz drummer Jason Marsalis, youngest brother of Wynton Marsalis (Hon.’92) and Branford Marsalis, trumpet player and composer Irvin Mayfield, and composer and jazz pianist Courtney Bryan. At the time, he had no idea what trajectory their careers and lives might take.

The filmmaker followed the trio intermittently from 1998 to 2002. His first documentary, Jazz Dreams, was released in 2003, and he resumed shooting them in 2008 and 2010 and recently completed Jazz Dreams II, which includes footage dating back to 1998. The film’s scope is wider than its predecessor, following the three from high school, through the destruction of Hurricane Katrina, to the present, documenting their lives as musicians, entrepreneurs, and parents. And the film’s subjects are now highly respected artists: Marsalis is one of the nation’s most prominent jazz drummers, Mayfield a Grammy Award winner, and Bryan a successful composer and jazz pianist. The documentary won a 2012 Telly Award and will be screened at the Boston International Film Festival tomorrow, April 17.

Poister, a College of Communication associate professor of film and television, will screen and discuss the making of Jazz Dreams II tonight as part of the BU Cinematheque series, the COM program that brings accomplished filmmakers to campus to screen and discuss their work.

“Jazz Dreams is about young people who are committed to what they want to do and obstacles in their lives,” Poister says. “I’m fascinated by the process of growing up, finding an identity, and finding work that you really want to do and finding a way to do it. But the film is also about African American music and how important it is to American culture and world music.”

Poister comes to his subject matter with a deep personal knowledge of jazz. Prior to becoming a filmmaker, he studied jazz at Berklee College of Music and has released two albums. He shifted to film and has produced nationally broadcast documentaries for the PBS series Nova, won a Telly and Accolade Award for his documentary The Spirit of Hiroshima, which follows a Japanese family in contemporary Hiroshima as they take their children to a ceremony commemorating the 1945 atomic bombing of the city. He and Susan Walker, a COM associate professor of journalism, coproduced the documentary A Tale of Two Teens—which explores AIDS in South Africa from the perspective of teenage girls. Poister has worked as a producer, writer, and cinematographer; he founded Intercultural Films, a company producing cultural-related programming, in 1995.

He will be joined onstage at tonight’s Cinematheque by Jazz Dreams star Bryan, who has produced and released two recordings and is currently pursuing a doctorate in music composition at Columbia University.

BU Today spoke to Poister about his new film, his career, and his love of jazz.

BU Today: How did you get the idea for Jazz Dreams?

Poister: A couple of things happened. First, two of my favorite documentaries are stories that follow people for long periods of time—Michael Apted’s 7-Up series, where he returns every seven years to this group of people in London, and the film Hoop Dreams. I affectionately titled my film off of Hoop Dreams, which is about inner-city basketball players in Chicago as they play basketball and try to get out of the ghetto.

I was living in New Orleans and decided it would be a good place to look for young jazz musicians; it’s the city where jazz was born. I was thinking about the future of jazz and what kind of young people would want to carry it on when there are so many grander things they could do. So I started asking around in the clubs and schools and to look for people who would be interesting to follow for a long time.

That process was kind of interesting in itself, because I asked for a recommendation and somebody suggested I talk to Irvin Mayfield, who was 19 and living in his parent’s house. He had this incredible spark and enthusiasm about him. His energy was so strong, and I thought he’d be a great subject. I asked him to recommend someone else, and his best friend was Jason Marsalis. So I went to talk to Jason, and he thought it was fun. I wanted one more person to focus on, and I was looking for a woman. I ended up going to an arts high school, the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, where they have trained a lot of successful musicians, and a teacher there recommended Courtney Bryan. She’s only 16, he said, but there’s something special about her, and she is going to have something to offer. She was very shy, but very talented. Once I had my three people, I started traveling every weekend to see what they were doing and following their lives. I did that for almost five years, took a break from it, and went back almost eight years after that.

What about these three convinced you they were compelling enough to follow? Was it hard to convince them to work with you for such an extensive period?

What I saw in them was a passion for music and their willingness to risk everything. There was not a single moment of doubt in any of them that this would not be what they would do for the rest of their lives. Irvin said, “I don’t want a safety net. I have friends who are getting degrees in engineering and want to be jazz musicians, but I’m going to do this whether I make money or I don’t make money.” There was something about that that was very unusual to me, but when I started the project it hit me that my audience would be young people. I wanted to inspire them and show them that if you love something and you stick with it, you will succeed. Maybe not exactly the way you thought you would, but you will find success. I thought it was inspiring to have these young people setting off on a course for their lives completely guided by the love, passion, and commitment for art.

I’ve been lucky with these people, and I also don’t ask a lot of them. Part of it is that they become proud when you highlight them in a documentary like this. And you become friends with them.

Did your background studying jazz at Berklee College of Music give you special insight about your subjects?

I can relate to musicians because I am one. I play violin and guitar. I don’t share quite the same level of talent as the people in my film—they are pretty amazing. But I understand what it is like to love to do something enough to do it and not let anything stop you. A lot of musicians have that. They are often very committed to what they are doing, and they have to do it, whether they do it professionally or nonprofessionally. I still play music, and although I’m not doing it to make a living, nothing can stop me from doing it.

How did you morph from jazz musician to filmmaker?

I’ve always been interested in film, but I didn’t head for that right away. I made my first film, a spy film, when I was 12. But I got bit by the music bug in high school, and that took over. I was one of those who made the decision that I didn’t want to try to make a living out of it. It looked too precarious to me. I didn’t have the bravery that the people in my film have. But they are also more talented than I am. I always associated music with film because of the combination of images and music. I finally decided to study film and went to NYU. Then I got a master’s degree in film and television from Syracuse University and eventually went back there for my PhD in sociology.

How do you approach filming a documentary?

I try to quietly stay around, and only use a two-person crew. Jason used to make jokes, because I would show up with the camera, and he would pretend to be the camera and talk to the camera, so they like being in it. I’m not trying to glorify them, and I think they appreciate that.

What are you working on next?

I’m working on experimental things. I want to do something that walks the line between fiction and nonfiction, and I’m almost finished with the new film. The story is fiction, but it uses real footage and looks like a real documentary. The idea is that I would shoot my own footage, some in Russia, and then add in clips from James Bond movies and archival propaganda films.

What I’m doing is trying to explore the boundaries of nonfiction, because I don’t really know how much of a difference there is between fiction and nonfiction. They blend together. I’m trying to get people to ask questions. I plan to submit it to festivals. I’ve never done a film like this before, so it’s new terrain for me. BU has been supportive of me and my work and giving me the time to work on these things.

Does being an active filmmaker make you a better teacher and does it benefit your students?

I think it’s vital. I wouldn’t be comfortable if I wasn’t actively doing it. They seem energized that I’m doing something now and I can understand what they are grappling with. Making films gives me a lot more to talk about, and I think my students and I engage more this way.

Watch the trailer for Jazz Dreams II above.

Jazz Dreams II screens tonight, Tuesday, April 16, at 7 p.m., followed by a talk by Geoffrey Poister and Courtney Bryan, at the College of Communication, Room 101, 640 Commonwealth Ave. The event, part of the BU Cinematheque series, is free and open to the public.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.