Boston School Assignment Plan Marks New Era

SED dean says system offers parents transparency in school choice

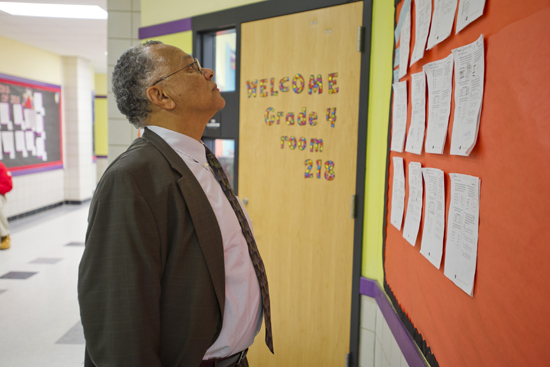

Hardin Coleman, dean of the School of Education, headed a committee that came up with a sweeping new plan, approved last week, that revamps the assignment process for Boston public schools. Photos by Cydney Scott

Public education in Boston has a long way to go in terms of school quality. But when the Boston School Committee voted on March 13 to approve a new school assignment plan, it marked the end of a flawed 25-year zone-based system developed under court-ordered desegregation and the beginning of a new era of transparency in school choice, says Hardin Coleman, dean of the School of Education and head of the 27-member committee that spent a year hammering out the new plan.

Beginning in fall 2014, Boston parents will be able to choose from at least six schools based on a variety of factors and priorities, including performance on MCAS, the commonwealth’s standards-based assessment program, school capacity, and families’ distance from schools. The so-called “home-based model,” which passed six to one, is designed to correct some of the inequities in the current three-zone system, where parents were offered approximately two dozen school choices over a large geographical area. That plan was established in February 1989 by federal judge W. Arthur Garrity, who had ordered the controversial 1974 busing to desegregate the city’s schools and continued to play a role in the tumultuous years following.

The new assignment plan delivers on a promise made by Mayor Thomas M. Menino (Hon.’01) to provide parents with more confidence about school choice and allows more children from the same neighborhood to attend the same school. Menino commends the School Committee vote, saying it was “a long time coming” and calling the new formula “a more predictable and equitable student assignment system that emphasizes quality and keeps our children close to home.”

Not everyone supports the new plan. City Councilor John Connolly, who has announced plans to run for mayor, says that the Boston Public Schools have simply “replaced the current convoluted school lottery with a different convoluted school lottery.”

BU Today spoke with Coleman in the wake of the historic vote, and found him optimistic about a new era of school choice, but realistic about the sobering challenge of improving schools to the point where parents have more high-quality schools to choose from.

BU Today: How are you feeling about the outcome of this long process?

Coleman: I am pleasantly surprised with the final options. They really did evolve out of a lot of community involvement and consideration and were different than any model we started with. Once we compared it to other options, we weren’t surprised the community turned to it as the best one; it is so transparent it was the logical choice.

What was the opposition to the new plan?

The opposition to the model was not as strong as the fear that we were not addressing the major education problem, which is not enough quality seats for the number we have. Opposition that was most vocal came from those who wanted no decision at all before first improving school quality. But most people were pleased with the work of the committee, and given how effective the committee was on addressing the assignment, we’re hoping we can now take on the issue of quality. Until you improve quality, there will always be kids who are victims of geography.

What was the thrust of the committee’s work?

The charge of the committee—and it’s a fascinating charge given Boston’s history—was how do you create quality close to people’s homes? One of the great things the committee was able to do was not make people choose between conflicting priorities. We had to find a model that delivered equal access close to home, and we succeeded at that. In the recommendations we were very clear that this is only a partial step. The big step is how do we define quality. We need to create transparent data sets, so people can type in their address and find out right away where the closest quality school is. That is one of the outcomes of this process. The first thing our committee asked for was that data be transparent and that parents be able to audit it. The data is now open source, in the public sphere. We worked hand in glove with Harvard, Boston College, and MIT to analyze data in a cooperative way, which is what makes Boston a wonderful place to be.

Does this plan benefit everyone?

I won’t say everyone does better. In the old system, there was a huge inequity in access. What this system does is improve access to quality for those who had low access. To make things more equitable, someone had to lose some resources. The zone model made some kids victims of their geography and other kids privileged, so if I’m in Mission Hill, within a half mile of all poor schools, I’m in poor shape. But in the current model, which is based on a huge geographic area, there are four tiers of schools: level one and level two are the good schools, level three not good, level four are the ones in turnaround status. I may be living in a certain area where most of the schools are level three and four, but in this system I now know I have at least two level two or one schools that I can put in my bucket so I’m competing equally with people in my neighborhood. We had to find a way to even the playing field, to make sure that every family has equal access. Until you can guarantee access, you’re not making a change.

What should be the next step for Boston schools?

My hypothesis about what needs to occur, why we all have to stay focused, and why the work is far from done, is to look at schools that are underperforming and make improvements and make sure they happen in those neighborhoods that have fewer high-quality schools. Let’s track these schools’ progress so they can get better. This assignment system really spotlights those values, and it will be easy to see where progress is made and where it’s not made, easy to see where the system could be held accountable in a way that zone models were not.

What did you learn during your time on the committee?

One thing was that it quickly became obvious that we’d been meeting once a month, but faced too many issues to deal with them effectively. So we, the 27 members, broke into a data group, a quality and equality group, and a community group, to make sure everyone was heard and engaged in the process. Those subcommittees met in between the major meetings. If any policy people end up writing about this, the subgroups helped us work through some really difficult issues.

Are there unique challenges Boston faces when it comes to school assignment that make it different from, say, Cambridge?

This plan is the best one we could find for Boston. Other models nationally, and in Cambridge, use class background to help with their assignment process. But this city can’t use class because we’re not a very diverse city; we’re very homogeneous. We’re only 13 percent Anglo.

Would you be interested in continuing to serve on the advisory committee if the mayor asks you?

The new plan won’t improve the schools by itself, so until the schools get better, I have let the mayor and Superintendent Carol Johnson know I’m delighted to participate. As a school of education here at BU, we’re very involved in the high-needs schools. Boston University is paired with the William M. Trotter Elementary School and Boston English High School.

Have we reached the end of the era of school integration? How important is it?

This has been my family’s Christmas argument for 30 years. You go back to Brown v Board of Education and even before that, and the key assumption is that if you’re going to improve academic outcomes for kids of color, you have to educate them with wealthy kids and white kids. Separate but equal was found to be unconstitutional. Studies found that kids who went to integrated schools had better health and educational outcomes, but also found that these kids had smaller classrooms and better teachers. So was it the integration or the resources? It’s a question about which scholars disagree. But I would say, if you provide the right resources and personnel to schools where kids are poor and underperforming, that’s the ticket.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.