Ferreting Out Faux Bordeaux

SHA alum earns national reputation as wine sleuth

When James Grandison forked over about $5,000 for some coveted Bordeaux wine, including a bottle of 1949 Château Lafleur, he was excited about the auction-house find and felt it was worth the splurge. The Berkeley, Calif., theology teacher had started buying $40 bottles of wine in the mid 1990s. “Two years later the value was at $130,” he says. “In the 2000s I ordered wines at $350 a bottle and three years later, when I actually received them in my hands, they were worth $2,000 a bottle.”

So Grandison (STH’94) reasoned that he could justify plunking down the $5,000. What he didn’t know was that the Lafleur was a fake. Fortunately for him, he was meeting his friend Maureen Downey for lunch after the auction, and because he didn’t want to leave the wine in his car, where the heat could sour it, he brought the bottles into the restaurant with him.

Downey (SHA’94), an expert in rare and fine wine, examined the alleged Lafleur and delivered the bad news. “I hate to tell you this,” she told Grandison, “but this bottle doesn’t appear to be consistent.”

“What does that mean?” he asked.

“The glass is correct, but I don’t like the paper, I don’t like the printing, the capsule looks funny….The cork could be a new cork in an old bottle. Based on all these factors,” she said, “I think you should get up from this lunch right now, drive back to the auction house, and return it and say you expect a refund.”

Grandison took her suggestion. When he told the auctioneers that Maureen Downey had inspected his purchase and found it suspect, they returned his money—“No problem,” he recalls.

Authenticating wine is just one part of Downey’s work, although it is the part that’s turned her into a sought-after commentator, with last month’s indictment of suspected wine counterfeiter Rudi Kurniawan, a.k.a. “Dr. Conti.” Downey is one of just a handful of authentication experts in the rare and fine wine industry, and she began airing doubts about Kurniawan’s “magic cellar” almost a decade ago. Now vindicated, she’s been doing interviews with Vanity Fair, Inside Edition, Fox Business, and MSNBC’s Crime, Inc.

Based in San Francisco, Downey runs Chai Consulting. (Chai, pronounced “shay,” is French for cellar. “I don’t make tea,” she says.) With employees’ help, she manages clients’ massive collections of high-end wines—usually bottles numbering in the thousands, often worth millions of dollars. She transforms cellars chockablock with haphazard piles of boxes into neatly arranged repositories organized by spreadsheet and a labeling system. She helps clients cull their collections to adapt to their changing tastes or lifestyles, figuring out which bottles to sell and finding the best price for them, and by the same token getting them deals when they want to restock. She acts as an appraiser, sometimes in sticky situations arising from a divorce or inheritance. She teaches about wine and testifies about it as an expert witness in court. And it all started at BU’s School of Hospitality Administration.

“I took a bar management class freshman year,” she recalls. “Sophomore year, I went abroad, took a four-unit course on the wines of France, and traveled through the French wine regions.” And as a junior, she and three other young women represented BU in the student division of sommelier Kevin Zraly’s International Wine and Spirits Competition, a male-dominated environment. “We walked in and were laughed at,” she recalls, “and we smoked everybody. We won. That was really when the door opened for me.”

Downey got certified as a sommelier shortly after graduation and was soon hired as manager of Tavern on the Green, the once famous, now defunct restaurant in New York City’s Central Park. By 2000, she decided she didn’t want to work another Christmas. She became a wine specialist for a series of auction houses and earned more wine certificates before striking out on her own in 2005.

Since then, she has made a national name for herself as a smart buyer, seller, organizer, and overall manager of the collections of a range of clients with one thing in common. “Once you’re in the habit of buying and aging wine,” Grandison says, “it’s difficult to stop. It presents organizational and storage problems. That’s where someone like Maureen comes in—and actually, there are not a lot of people like her.”

Downey has to be as much psychologist as wine expert at times. “There is a compulsion to collecting,” she says. “They all have fierce separation anxiety when it comes time to sell.” In Grandison’s case, she says, “every bottle has a story,” a sentimental attachment. “He was like, ‘Ohh, Mo, you’re killing me.’”

“We’ve had standoffs,” Grandison confirms with a laugh.

But when Downey realized Grandison simply wasn’t drinking the higher-alcohol-content California wine he had gone for in his late 20s and early 30s, she pointed out that if he got rid of some, he’d have money to buy the European vintages he was developing a preference for. And after all, Grandison says, “I consider myself a wine drinker” more than a collector.

The Madoff of Merlot

Downey has had more serious standoffs, in the realm of wine-buying public opinion, over the existence of fraud in the market. “I’ve been a totally antifraud freak since 2000, and I was laughed at by a lot of the boys in New York,” she told SHA students when she visited the school this spring. As for Kurniawan, whom Downey calls “the Madoff of Merlot,” in 2002 he tried to sell her (at auction house Zachy’s) 1940s and ’50s bottles of Pomerol wines. When he couldn’t produce adequate documentation of their provenance, she refused to buy them. “Everybody thought I was crazy,” she says. “Everybody held him as this great guy, and I always felt there was something wrong.”

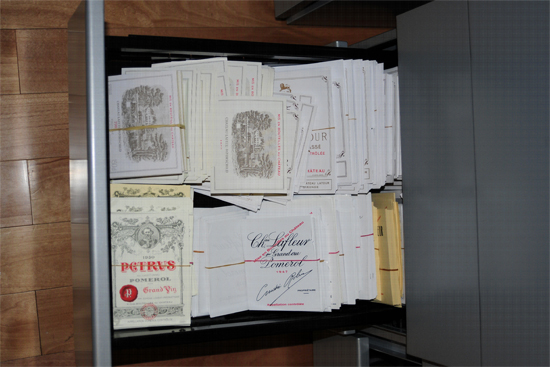

Indeed, Kurniawan succeeded in fooling some of the country’s biggest wine connoisseurs, dealers, and bloggers with his tales of rare wines found walled up in cellars in Europe. Eventually, the number of rare bottles he somehow produced strained credulity, the number of used high-end bottles he collected raised questions, and the threads of his alleged deception unraveled. In May, the FBI raided his home and found thousands of top wine labels, hundreds of corks and a corking device, sealing wax and rubber stamps, glue, stencils, instructions for fabricating labels, empty bottles soaking in the sink, and cheap bottles of Napa Valley wine markered with the names of classic Bordeaux to be impersonated. Kurniawan now stands trial on multiple counts of fraud.

Those labeling and corking materials were key: fraud detection has nothing to do with the taste of a wine, Downey says. “If you’ve got something that’s been in a bottle for 40 or 50 or 100 years, there’s going to be bottle variation.” Not to mention that some wines were transported in different types of barrels before even being bottled. “Some threads should carry through, but nobody on the planet has so much experience with these incredibly rare wines that they can say with any degree of accuracy, ‘Oh yeah, this is correct Petrus from 1920.’ Bulls–t.” If taste told the tale, she points out, Kuniawan never would have pulled off the giant con he’s now charged with.

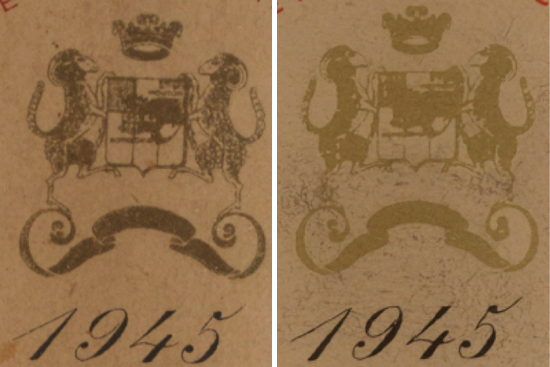

Downey’s approach when studying bottles and preparing authentication reports for clients is more about forensics than flavor. She takes into account paper stock, printing quality, and the oxidation rate of label paper. She contacts the relevant producers (she knows them all and is fluent in French) and brings to bear historical knowledge about tin capsules and what colors of glass were used to bottle what brands when. “If you see a bottle where the label looks like hell but the capsule looks pristine, that’s like a 20-year-old’s body with a 90-year-old’s face,” she says. “They should have aged together. These are all errors that counterfeiters make.”

But wine buyers shouldn’t jump to conclusions, Downey cautions. The fakes “represent such a small fraction of the market.”

And a healthy, growing market it is. Total wine sales in the United States jumped 5.3 percent, to 347 million cases, in 2011. The Wine Institute estimates the retail value of that at $32.5 billion. The wine industry in Napa Valley alone—and that California county is a mere eighth the size of Bordeaux, just one French growing region—generates 40,000 jobs.

That’s why Downey believes that wine education programs at hospitality schools like SHA are so important.

“This is a real business, this is a lucrative business, and it’s a viable career,” the alum told SHA students during her visit. “There’s nothing but opportunity for people who are smart, who are capable, and who work hard.” Her advice? Get educated, and “start in wine early.”

Patrick Kennedy can be reached at plk@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.